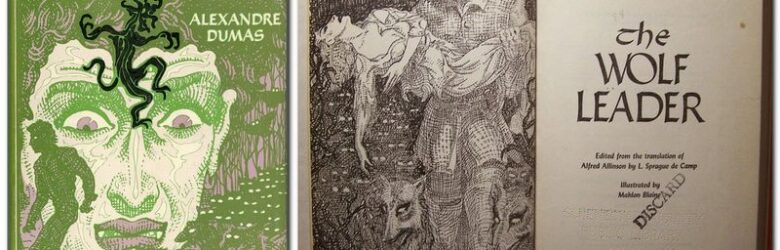

#WerewolvesWednesday: The Wolf-Leader (3)

A werewolf story by Alexandre Dumas père. Chapter III: Agnelette The Baron took the weapon which Engoulevent handed him, and deliberately examined the boar-spear from point to handle, without saying a word. On the handle had been carved a little wooden shoe, which had served as Thibault’s device while making the tour of France, as thereby […]

A werewolf story by Alexandre Dumas père.

Chapter III: Agnelette

The Baron took the weapon which Engoulevent handed him, and deliberately examined the boar-spear from point to handle, without saying a word. On the handle had been carved a little wooden shoe, which had served as Thibault’s device while making the tour of France, as thereby he was able to recognise his own weapon. The Baron now pointed to this, saying to Thibault as he did so:

“Ah, ah, Master Simpleton! There is something that witnesses terribly against you! I must confess, this boar-spear smells to me uncommonly of venison—by the devil, it does! However, all I have now to say to you is this: You have been poaching, which is a serious crime; you have perjured yourself, which is a great sin. I am going to enforce expiation from you for the one and for the other, to help toward the salvation of that soul by which you have sworn.”

Whereupon, turning to the pricker, he continued: “Marcotte, strip off that rascal’s vest and shirt, tie him to a tree with a couple of the dog leashes, and give him thirty-six strokes across the back with your shoulder belt—a dozen for his perjury and two dozen for his poaching. No, I make a mistake—a dozen for poaching and two dozen for perjuring himself. God’s portion must be the largest.”

This order caused great rejoicing among the menials, who thought it good luck to have a culprit on whom they could avenge themselves for the mishaps of the day.

In spite of Thibault’s protestations, who swore by all the saints in the calender, that he had killed neither buck, nor doe, neither goat nor kidling, he was divested of his garments and firmly strapped to the trunk of a tree; then the execution commenced.

The pricker’s strokes were so heavy that Thibault, who had sworn not to utter a sound, and bit his lips to enable himself to keep his resolution, was forced at the third blow to open his mouth and cry out.

The Baron, as we have already seen, was about the roughest man of his class for a good thirty miles round, but he was not hard-hearted, and it was a distress to him to listen to the cries of the culprit as they became more and more frequent As, however, the poachers on His Highness’s estate had of late grown bolder and more troublesome, he decided that he had better let the sentence be carried out to the full, but he turned his horse with the intention of riding away, determined no longer to remain as a spectator.

As he was on the point of doing this, a young girl suddenly emerged from the underwood, threw herself on her knees beside the horse, and, lifting her large, beautiful eyes—wet with tears—to the Baron, cried:

“In the name of the God of mercy, my Lord, have pity on that man!”

The Lord of Vez looked down at the young girl. She was indeed a lovely child, hardly sixteen years of age, with a slender and exquisite figure, a pink and white complexion, and large blue eyes, soft and tender in expression. A crown of fair hair fell in luxuriant waves over her neck and shoulders, escaping from beneath the shabby little grey linen cap that vainly attempted to imprison them.

All this the Baron took in with a glance, in spite of the humble clothing of the beautiful suppliant, and as he had no dislike to a pretty face, he smiled down on the charming young peasant girl, in response to the pleading of her eloquent eyes.

But, as he looked without speaking, and all the while the blows were still falling, she cried again, with a voice and gesture of even more earnest supplication.

“Have pity, in the name of Heaven, my Lord! Tell your servants to let the poor man go, his cries pierce my heart.”

“Ten thousand fiends!” cried the Grand Master; “you take a great interest in that rascal over there, my pretty child. Is he your brother?”

“No, my Lord.”

“Your cousin?”

“No, my Lord.”

“Your lover?”

“My lover! My Lord is laughing at me.”

“Why not? If it were so, my sweet girl, I must confess I should envy him his lot.”

The girl lowered her eyes.

“I do not know him, my Lord, and have never seen him before to-day.”

“Without counting that now she only sees him wrong side before” Engoulevent ventured to put in, thinking that it was a suitable moment for a little pleasantry.

“Silence, sirrah!” said the Baron sternly. Then, once more turning to the girl with a smile.

“Really!” he said. “Well, if he is neither a relation nor a lover, I should like to see how far your love for your neighbour will let you go. Come, a bargain, pretty girl!”

“How, my Lord?”

“Grace for that scoundrel in return for a kiss.”

“Oh! with all my heart!” cried the young girl. “Save the life of a man with a kiss! I am sure that our good Cure himself would say there was no sin in that.”

And without waiting for the Baron to stoop and take for himself what he had asked for, she threw off her wooden shoe, placed her dainty little foot on the tip of the wolf-hunter’s boot, and, taking hold of the horse’s mane, lifted herself with a spring to the level of the hardy huntsman’s face. There, of her own accord, she offered him her round cheek, fresh and velvety as the down of an August peach.

The Lord of Vez had bargained for one kiss, but he took two; then, true to his sworn word, he made a sign to Marcotte to stay the execution.

Marcotte was religiously counting his strokes; the twelfth was about to descend when he received the order to stop, and he did not think it expedient to stay it from falling. It is possible that he also thought it would be as well to give it the weight of two ordinary blows, so as to make up good measure and give a thirteenth in; however that may be, it is certain that it furrowed Thibault’s houlders more cruelly than those that went before. It must be added, however, that he was unbound immediately after.

Meanwhile the Baron was conversing with the young girl.

“What is your name, my pretty one?”

“Georgine Agnelette, my Lord, my mother’s name! but the country people are content to call me simply Agnelette.”

“Ah, that’s an unlucky name, my child,” said the Baron.

“In what way my Lord?” asked the girl.

“Because it makes you a prey for the wolf, my beauty. And from what part of the country do you come, Agnelette?”

“From Preciamont, my Lord.”

“And you come alone like this into the forest, my child? that’s brave for a lambkin.”

“I am obliged to do it, my Lord, for my mother and I have three goats to feed.”

“So you come here to get grass for them?”

“Yes, my Lord.”

“And you are not afraid, young and pretty as you are?”

“Sometimes, my Lord, I cannot help trembling.”

“And why do you tremble?”

“Well, my Lord, I hear so many tales during the winter evenings about werewolves that when I find myself all alone among the trees, with no sound but the west wind and the branches creaking as it blows through them, I feel a kind of shiver run through me, and my hair seems to stand on end. But when I hear your hunting horn and the dogs crying, I feel at once quite safe again.”

The Baron was pleased beyond measure with this reply of the girl’s, and stroking his beard complaisantly, he said:

“Well, we give Master Wolf a pretty rough time of it; but, there is a way, my pretty one, whereby you may spare yourself all these fears and tremblings.”

“And how, my Lord?”

“Come in future to the Castle of Vez; no were-wolf, or any other kind of wolf, has ever crossed the moat there, except when slung by a cord on to a hazel-pole.”

Agnelette shook her head.

“You would not like to come? and why not?”

“Because I should find something worse there than the wolf.”

On hearing this, the Baron broke into a hearty fit of laughter, and, seeing their Master laugh, all the huntsmen followed suit and joined in the chorus. The fact was, that the sight of Agnelette had entirely restored the good humour of the Lord of Vez, and he would, no doubt, have continued for some time laughing and talking with Agnelette, if Marcotte, who had been recalling the dogs, and coupling them, had not respectfully reminded my Lord that they had some distance to go on their way back to the Castle. The Baron made a playful gesture of menace with his finger to the girl, and rode off followed by his train.

Agnelette was left alone with Thibault. We have related what Agnelette had done for Thibault’s sake, and also said that she was pretty.

Nevertheless, for all that, Thibault’s first thoughts on finding himself alone with the girl, were not for the one who had saved his life, but were given up to hatred and the contemplation of vengeance.

Thibault, as you see, had, since the morning, been making rapid strides along the path of evil.

“Ah! if the devil will but hear my prayer this time,” he cried, as he shook his fist, cursing the while, after the retiring huntsmen, who were just out of view, “if the devil will but hear me, you shall be

paid back with usury for all you have made me suffer this day, that I swear.”

“Oh, how wicked it is of you to behave like that!” said Agnelette, going up to him.

“The Baron is a kind Lord, very good to the poor, and always gently behaved with women.”

“Quite so, and you shall see with what gratitude I will repay him for the blows he has given me.”

“Come now, frankly, friend, confess that you deserved those blows,” said the girl, laughing.

“So, so!” answered Thibault, “the Baron’s kiss has turned your head, has it, my pretty Agnelette?”

“You, I should have thought, would have been the last person to reproach me with that kiss, Monsieur Thibault. But what I have said, I say again; my Lord Baron was within his rights.”

“What, in belabouring me with blows!”

“Well, why do you go hunting on the estates of these great lords?”

“Does not the game belong to everybody, to the peasant just as much as to the great lords?”

“No, certainly not; the game is in their woods, it is fed on their grass, and you have no right to throw your boar-spear at a buck which belongs to my lord the Duke of Orleans.”

“And who told you that I threw a boar-spear at his buck?” replied Thibault, advancing towards Agnelette in an almost threatening manner.

“Who told me? why, my own eyes, which, let me tell you, do not lie. Yes, I saw you throw your boar-spear, when you were hidden there, behind the beech-tree.”

Thibault’s anger subsided at once before the straightforward attitude of the girl, whose truthfulness was in such contrast to his falsehood.

“Well, after all,” he said, “supposing a poor devil does, once in a way, help himself to a good dinner from the superabundance of some great lord! Are you of the same mind, Mademoiselle Agnelette, as the judges who say that a man ought to be hanged just for a wretched rabbit? Come now, do you think God created that buck for the Baron more than for me?”

“God, Monsieur Thibault, has told us not to covet other men’s goods; obey the law of God, and you will not find yourself any the worse off for it!”

“Ah, I see, my pretty Agnelette, you know me then, since you call me so glibly by my name?”

“Certainly I do; I remember seeing you at Boursonnes, on the day of the fete; they called you the beautiful dancer, and stood round in a circle to watch you.”

Thibault, pleased with this compliment, was now quite disarmed.

“Yes, yes, of course,” he answered, “I remember now having seen you; and I think we danced together, did we not? but you were not so tall then as you are now, that’s why I did not recognise you at first, but I recall you distinctly now. And I remember too that you wore a pink frock, with a pretty little white bodice, and that we danced in the dairy. I wanted to kiss you, but you would not let me, for you said that it was only proper to kiss one’s vis-a-vis, and not one’s partner.”

“You have a good memory, Monsieur Thibault!”

“And do you know, Agnelette, that during these last twelve months, for it is a year since that dance, you have not only grown taller, but grown prettier too; I see you are one of those people who understand how to do two things at once.”

The girl blushed and lowered her eyes, and the blush and the shy embarrassment only made her look more charming still.

Thibault’s eyes were now turned towards her with more marked attention than before, and, in a voice, not wholly free from a slight agitation, he asked:

“Have you a lover, Agnelette?”

“No, Monsieur Thibault,” she answered, “I have never had one, and do not wish to have one.”

“And why is that? Is Cupid such a bad lad that you are afraid of him?”

“No, not that, but a lover is not at all what I want.”

“And what do you want?”

“A husband.”

Thibault made a movement, which Agnelette either did not, or pretended not to see.

“Yes,” she repeated, “a husband. Grandmother is old and infirm, and a lover would distract my attention too much from the care which I now give her; whereas, a husband, if I found a nice fellow who would like to marry me, a husband would help me to look after her in her old age, and would share with me the task which God has laid upon me, of making her happy and comfortable in her last years.”

“But do you think your husband,” said Thibault, “would be willing that you should love your grandmother more than you loved him? and do you not think he might be jealous at seeing you lavish so much tenderness upon her?”

“Oh,” replied Agnelette, with an adorable smile, “there is no fear of that, for I will manage to give him such a large share of my love and attention that he will have no cause to complain. The kinder and more patient he is with the dear old thing, the more I shall devote myself to him, the harder I shall work to make sure nothing is wanting in our little household. You see me looking small and delicate, and you doubt that I should have strength for this, but I have plenty of spirit and energy for work. And then, when the heart gives consent, one can work day and night without fatigue. Oh! how I should love the man who loved my grandmother! I promise you that she, my husband, and I—we should be three happy folks together.”

“You mean that you would be three very poor folks together, Agnelette!”

“And do you think the loves and friendships of the rich are worth a farthing more than those of the poor? At times, when I have been loving and caressing my grandmother, Monsieur Thibault, and she takes me on her lap, clasping me in her poor weak trembling arms, and puts her dear old wrinkled face against mine, I feel my cheek wet with the loving tears she sheds. I begin to cry myself, and I tell you, Monsieur Thibault, so soft and sweet are my tears that no woman or girl, be she queen or princess, has ever, even in her happiest days, known such a real joy as mine. And yet, there is no one in all the country round who is as destitute as we two are.”

Thibault listened to what Agnelette was saying without answering; his mind was occupied with many thoughts, such thoughts as are indulged in by the ambitious; but his dreams of ambition were disturbed at moments by a passing sensation of depression and disillusionment.

He, the man who had spent hours at a time watching the beautiful and aristocratic dames of the Court of the Duke of Orleans as they swept up and down the wide entrance stairs; who had often passed whole nights gazing at the arched windows of the Keep at Vez when the whole place was lit up for some festivity—he, that same man, now asked himself whether what he had so ambitiously desired—a lady of rank and a rich dwelling—would, after all, be worth as much as a thatched roof and this sweet and gentle girl called Agnelette. And it was certain that if this dear and charming little woman were to become his, he would, in turn, be envied by all the earls and barons in the countryside.

“Well, Agnelette,” said Thibault “and suppose a man like myself were to offer himself as your husband, would you accept him?”

It has been already stated that Thibault was a handsome young fellow, with fine eyes and black hair, and that his travels had left him something better than a mere workman. And it must further be borne in mind that we readily become attached to those on whom we have conferred a benefit, and Agnelette had, in all probability, saved Thibault’s life; for, under such strokes as Marcotte’s, the victim would certainly have been dead before the thirty-sixth had been given.

“Yes,” she said, “if it would be a good thing for my grandmother?”

Thibault took hold of her hand.

“Well then, Agnelette,” he said “we will speak again about this, dear child, and that as soon as may be.”

“Whenever you like, Monsieur Thibault.”

“And you will promise faithfully to love me if I marry you, Agnelette?”

“Do you think I should love any man besides my husband?”

“Never mind, I want you just to take a little oath, something of this kind, for instance; Monsieur Thibault, I swear that I will never love anyone but you.”

“What need is there to swear? the promise of an honest girl should be sufficient for an honest man.”

“And when shall we have the wedding, Agnelette?” and in saying this, Thibault tried to put his arm round her waist.

But Agnelette gently disengaged her self.

“Come and see my grandmother,” she said, “it is for her to decide about it; you must content yourself this evening with helping me up with my load of heath, for it is getting late, and it is nearly three miles from here to Preciamont.”

So Thibault helped her as desired and then accompanied her on her way home as far as the forest fence of Billemont, that is, until they came in sight of the village steeple. Before parting, he begged pretty Agnelette so earnestly for one kiss as an earnest of his future happiness that at last she consented. Then, far more agitated by this one kiss than she had been by the Baron’s double embrace, Agnelette hastened on her way, despite the load she was carrying on her head, which seemed far too heavy for so slender and delicate a creature.

Thibault stood for some time looking after her as she walked away across the moor. All the flexibility and grace of her youthful figure were brought into relief as she lifted her pretty, rounded arms to support the burden upon her head, and, silhouetted against the dark blue of the sky, she made a delightful picture.

At last, having reached the outskirts of the village, where the land dipped at that point, she suddenly disappeared, passing out of sight of Thibault’s admiring eyes. He gave a sigh and stood still, plunged in thought. But it was not the satisfaction of knowing that this sweet and good young creature might one day be his that had caused his sigh. Quite the contrary.

He had wished for Agnelette because she was young and pretty, and because it was part of his unfortunate disposition to long for everything that belonged or might belong to another. His desire to possess Agnelette had been quickened by the innocent frankness with which she had talked to him, but it had been a matter of fancy rather than of any deeper feeling—of the mind, and not of the heart.

Thibault was incapable of loving as a man ought to love when, being poor himself, he loves a poor girl. In such a case, there should be no thought, no ambition beyond the wish that his love may be returned. But it was not so with Thibault. On the contrary, the farther he walked away from Agnelette—leaving, it would seem, his good genius farther behind him with every step—the more urgently did his envious longings begin again to torment his soul.

It was dark when he reached home.

…to be continued.