Niki de Saint Phalle in Milan

I already wrote about Niki de Saint Phalle this summer, in prospect of visiting her Tarot Garden with some friends, and I was very lucky not only because we could manage the visit but also because a large exhibition on her work just arrived in Milan. The show is at the Museum of Cultures (you might […]

I already wrote about Niki de Saint Phalle this summer, in prospect of visiting her Tarot Garden with some friends, and I was very lucky not only because we could manage the visit but also because a large exhibition on her work just arrived in Milan. The show is at the Museum of Cultures (you might remember it from that Picasso exhibition I didn’t like), and it’ll stay on for another month, and it’s gorgeous from many points of view: the pieces are obviously stunning, the chronological narration works very well, and the staging is impressive.

“I’m Niki de Saint Phalle, and I create monumental sculptures.”

That’s the quote chosen to open the exhibition, and the curators will stress this aspect many times — for the Nanas, for the Tarot Garden, for the Totems — as one of the ways Saint Phalle chose to assert her autonomy as an artist: the dimension of her works.

Niki de Saint Phalle knew that in the history of art, few women had survived the chronicles as sculptors, and even fewer had dared to take their work into public spaces. You might remember what Vasari wrote about Properzia de Rossi, one of the first attested sculptors of our culture (I wrote about it here). Saint Phalle was one of these trailblazers and is now considered one of the most important artists of the 20th century, but the exhibition decides to start from her special connection to Italy, springing from a visit in Val d’Orcia. This connection will lead to the creation of her masterpiece of monumental sculpture, the Tarot Garden near Capalbio.

Her first significant contact with Italy occurred in 1957, when Saint Phalle stayed in Val d’Orcia and discovered 14th-century painting, its colours, and the modernity of a pre-Renaissance absence of perspective. This reassured the young self-taught artist, worried about her technical limitations. The small panels complementing her first displayed work are A City by the Sea and A Castle by the Lake by Stefano Di Giovanni Di Consolo, known as “the Sassetta”.

Saint Phalle might have seen them at the Pinacoteca of Siena, and some compositional elements suggest they inspired her piece Nightscape, which evokes the rolling Tuscan hills: coffee beans and pebbles glued together to represent houses or a city, with a central road branching off into a turreted detail, a few scattered trees in the Sienese style, a bicycle. The idea that it depicts the perched village of Talamone adds another layer of fascination: thirty years later, Saint Phalle returned to that stretch of coast to build her Tarot Garden in Capalbio. Her visit to Bomarzo deeply inspired her: the Sacred Wood would lay the basis for her masterpiece.

1. Public Shooting

Rebellious and sensitive, young Niki de Saint Phalle quickly realized that the roles assigned to women—wife, mother, homemaker—were way too restrictive. She dreamed big and found that art was the perfect way to express herself. Through a series of performances where she literally shot at a canvas, she made her explosive debut on the Paris art scene in the early ’60s.

“I was an angry young woman, but there are many young angry men and women who don’t become artists. I became an artist because I had no choice, no need to decide. It was my destiny.”

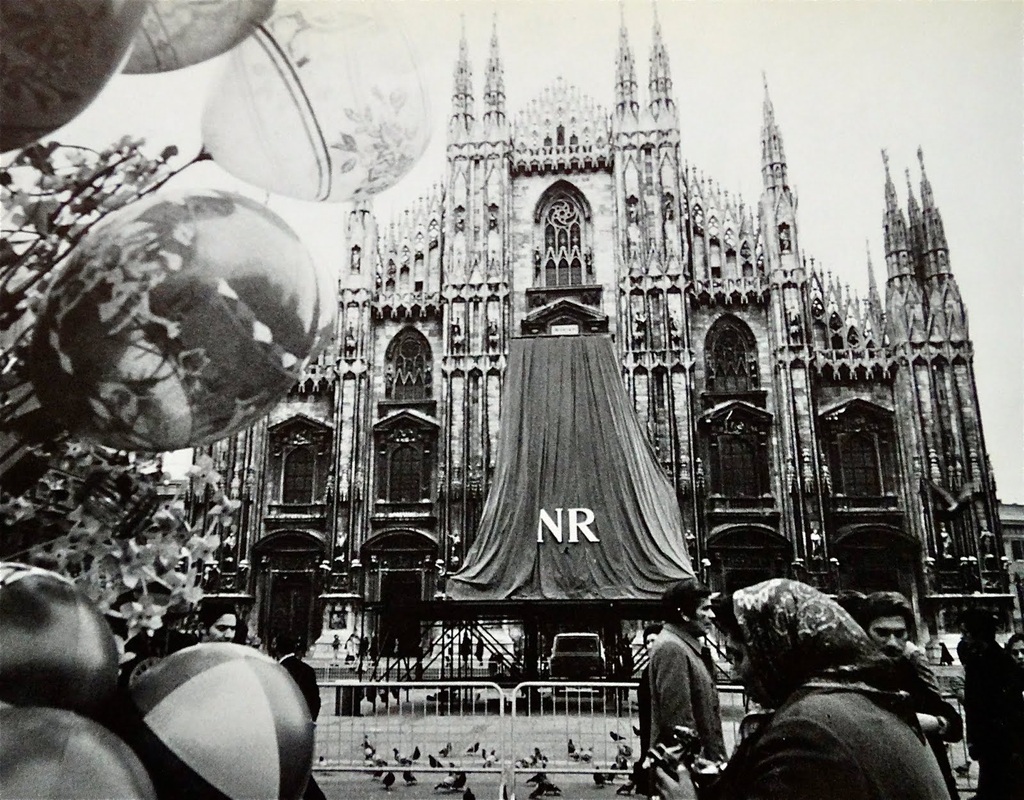

One of these performances also happened in Italy, in November 1970, when art critic Pierre Restany and gallery owner Guido Le Noci hosted a festival in Milan’s Piazza del Duomo to mark the 10th anniversary of Nouveau Réalisme. Part of this celebration was a group show at the Rotonda della Besana, where Saint Phalle displayed her work Composition à la trottinette (“Tir à la carabine”, 1961).

The real action, however, happened when Saint Phalle staged a live shooting performance at the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele. With a big crowd watching and police forming a cordon around the scene, Saint Phalle, dressed in a sleek black velvet suit and sporting a large cross necklace, took up a rifle and fired at a three-meter-high “altar” made of stuffed animals, sculptures of saints, Madonnas, and crucifixes. Red paint burst from hidden canisters behind the altar, splashing on the police, while smoke bombs filled the air. Just steps from the Duomo, her irreverence was impossible to ignore, and this wasn’t by chance as religion is one of the main targets of her early works.

2. Against the Church

Saint Phalle’s anticlerical stance is evident in her “Cathedrals” and “Altars” series, created in the early 1960s. She was raised under strict bourgeois conventions and educated in religious institutions following a false and hypocritical Catholic morality, and this would be a good moment to remind everyone that her father tried to stick his cock into his mouth while she was eleven years old. Except the exhibition decides not to do so, God forbid we might think a young woman was right in rejecting her family’s education, right?

Following her beliefs and her personal trauma, the artist shed this oppressive cloak by destroying the symbols representing the Church’s power—long the source of centuries-old abuses not so different from the ones she was witnessing at home. To her, this series was “a cry of rage against all the horrors committed in the name of any religion.”

“I decided early on to become a heroine.

And who would I be?

George Sand? Joan of Arc?

A female Napoleon?”

3. The Stance for Black Rights and the Nanas

Starting from 1963, the Civil Rights Act shook the United States and their struggle resonated deeply with Niki de Saint Phalle, who was spending those years in New York and California. From this period came works like Black Rosie (1965), The Lady Sings the Blues (1965), and Last Night I Had a Dream (1968), tributes to Rosa Parks, Billie Holiday, and Martin Luther‘s speech at the Lincoln Memorial.

The mutilated black body in The Lady Sings the Blues belongs to her series of “Crucifixions,” or “Prostitutes,” representing women sacrificed for humanity’s salvation like female messiahs. In the political context of the early 1960s United States, depicting the dismembered body of a Black woman was a bold stance. For Saint Phalle, it was about showing how that societal body was seen as “unfit” and thus marginalized.

Her stance with the Civil Rights movement wasn’t out of a white messiah complex.

Niki de Saint Phalle realized early in life the inequalities faced by women—in the family, at school, and in the art world. As a child, aside from the violence she went through herself, she watched her mother trapped in the domestic role dictated by the patriarchal society, and she decided to be a modern-day Prometheus to steal the fire of success and power from men. Her stunning piece defending the right to abortion should be hung in every hospital in the world.

The feminist classic The Second Sex (1949) by Simone de Beauvoir contributed to opening her eyes, while The White Goddess (1948) by Robert Graves showed her that it hadn’t always been this way: history had systematically erased women over centuries. She put the roles forced upon women at the centre of her work to obliterate them one by one: the mother, the sister, the nurse, the servant. One of the main institutions she shouted against was marriage, a de facto expectation her family had for her since her youth. In this regard, one of the most beautiful pieces in the exhibition is the bronze bride astride a monstrous, assembled horse. Pictures don’t do her justice.

Saint Phalle’s work, however, wasn’t only the destruction of oppressive archetypes. She created a new model through her monumental women—strong, mighty, larger than life—who weren’t passive muses but goddesses claiming their rightful share of power and opportunity. They were the Nanas.

“Communism and capitalism have failed. I think it’s time for a new matriarchal society. Do you think people would still starve if women were in charge? I can’t help but think they could create a world where I’d be happy to live.”

Initially crafted from papier-mâché and fabric, later in painted resin, the Nanas are a pop art rendition of the Great Mother from ancient myths—modern Willendorf Venuses with generous, abundant bodies and tiny heads and limbs. Over time, Niki de Saint Phalle created an entire army of these figures: feminist warriors, muses of gender equality, joyful and powerful, sexy and athletic, symbols of a society where women finally hold the reins of power.

Freed from the stereotypes that persist up to this day and glorify extreme thinness, the Nanas embody a positive, confident image of the body, celebrating its curves and roundness. Over time, the Nanas became monumental, transforming into Nana-Houses—protective spaces for dreaming and rediscovering oneself.

“How many Black figures have I made? Hundreds? Why would I, a white woman, create Black figures? I identify with all those who are marginalized, who have been persecuted in one way or another by society.”

Niki de Saint Phalle gave a voice to the most vulnerable because she believed that changing power dynamics—making space for women, respecting the sick and children—was the key to building a fairer society. She championed what had been silenced or pushed to the margins in Western culture and art. In the 1990s, she counterpointed this by creating a series titled Black Heroes, sculptures celebrating great African American athletes and musicians, including Josephine Baker, Michael Jordan, and Louis Armstrong.

4. The Tarot Garden

“The Tarot Garden is a tribute to all the women who, for centuries, were denied the right to reveal their strength and creativity; and when they dared to, they were mocked, scorned, repressed, burned as witches, or confined to asylums.”

There’s a better framing of this place in my previous post, I think, but Niki de Saint Phalle started building the Tarot Garden in 1978 on land gifted by Carlo and Nicola Caracciolo, thanks to their connection with Marella Caracciolo Agnelli, a long-time friend of the artist. The park features 22 sculptures, some monumental and walkable, inspired by Tarot cards, adorned with vibrant mosaics and ceramics, and it’s structured as a path where visitors encounter dragons and princesses, monsters and priestesses. The project was self-funded, it took nearly two decades to complete and the artist’s health wasn’t any better for it, especially considering that Saint Phalle lived inside the Empress sculpture for a while.

The Tarot Garden was her Parc Güell, a testament that women can dream big and achieve the same goals male artists can dare to dream. The room the exhibition dedicates to this work is one of the most joyously vibrant of the whole complex.

5. The Book on AIDS

In the 1980s, Niki de Saint Phalle became one of the first artists to publicly advocate for AIDS patients. Considered the plague of the modern era, AIDS was claiming the lives of her friends and collaborators, but it was surrounded by stigma deeply intertwined with bigotry, false morals and demonization of the queer community. The booklet she published in 1986 was titled AIDS: You Can’t Catch It Holding Hands, and it was both joyful and informative, witty and grounded in science, explaining what AIDS is, how to protect oneself, and how to help those affected.

“All caresses are allowed. Long live love.”

Her goal was to challenge the prevailing, moralizing narratives around illness and sexuality, offering new imagery and dancing the fine line between advocating for a responsible behaviour and banning judgment against patients. The book became a voice for marginalized communities left unsupported by public institutions. Even before campaigns like ACT UP (1987) or “Kissing Doesn’t Kill” (1989), she had already found a powerful way to get her message across.

In 1990, the book was distributed to all French high schools.

6. The surfaced trauma

My biggest issue with this exhibition is how they decide to underplay the horrific abuse her father attempted on her when she was little, and the sequence of psychological abuses this spanned: the letter bringing it back, the chronic migraines it caused, the betrayed trust of her own therapist covering for her father. These are all events that aren’t mentioned. And while I get not wanting an artist to be defined merely in the shade of her trauma, I think the result leaves Saint Phalle as “just another angry girl”. One with artistic talent, mind you. But little more than a punk. Which upsets me a lot.

Take Saint Phalle’s statement picked for this room:

“For me, the movie is about showing

what no one wants to see:

with a few exceptions,

the family is an arena where we devour one another.”

What a punk thing to say!

Except she knows what she’s talking about, she’s not just “an angry girl” or an avant-garder aiming to shock the middle class, and she’s right. Years before Sophie Ann Lewis’ book Abolish the Family, a book I think everyone should read, Saint Phalle addresses the impossible contradictions of the family institution.

In the movie Daddy, co-directed with Peter Whitehead, Niki de Saint Phalle unflinchingly depicts the power struggle between genders, ending with the symbolic shooting of the father figure. Though it’s worth mentioning that Saint Phalle wrote her own mother urging her not to go watch the movie (another detail the exhibition fails to mention) the mother figure is a passive observer which takes on a guilty role. The film was praised by Jacques Lacan and Jean-Luc Godard during its Paris premiere in February 1974 and, up to this day, her final monologue chills you down to the bones.

In 1994, Saint Phalle wrote a letter to her daughter Laura, which became the book Mon Secret: the book contains the confession of the attempted rape at the hand of her father, and puts into perspective the monsters she sought refuge with since her earlier age.

7. More female archetypes: the Mami Wata

The “Mami Wata”, a word derived from the English words “Mother” and “Water”, is a complex syncretic figure and if you want to know more about it, particularly in light of her contemporary significance, I suggest you read the thesis “Mami Wata, Diaspora, and Circum-Atlantic Performance” developed by Elyan Jeanine Hill for her degree Master of Arts in Culture and Performance at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Far from passively accepting cultural impositions, Mami Wata devotees appropriated

European images in order to understand outsiders and assert their right to reinterpret and reinvent

foreign customs.

More briefly, the Mami Wata is a water figure sometimes depicted as a mermaid and sometimes connected to the figure of the snake charmer, particularly through the persona of a woman who came to Europe in the late 19th century to perform in a circus as a snake charmer and whose story, so says the exhibition without providing more details, might have inspired Saint Phalle.

In the artist’s vision, the Mami Wata is the queen of the waters, a snake charmer, a fertility goddess, a greedy hoarder of wealth, vain and capricious, a tyrant to her followers, enchantress, prostitute, and jealous lover. Exotic and seductive, she’s the Statue of Liberty travelling astride a chariot of horses, a traveller who always remains a foreigner wherever she goes, and Saint Phalle feels a personal link to her.

8. The San Diego Totems

Going back to California after the unhealthy life in the Tarot Gardens had made her health worse, Saint Phalle directs her imagination to the iconography and concepts of North and Mesoamerican indigenous cultures.

“I’ve been fascinated by Native American culture for years. I feel they have a protective spirituality and a mysterious brilliance, and they are part of our Californian roots. After the Tarot Garden, it felt natural to be drawn to another form of spiritual art, so connected to Mother Earth and the Universe.”

She created Queen Califia’s Magical Circle, a sculpture park honouring Queen Califia, another victorious female figure astride a mythical creature. Califia was the mythical founder of California—beautiful, fierce, and leading a band of warrior women.

One of her final series, Skulls, reflects her way of addressing aging. Just a few years before Damien Hirst would shake the art word with his For the Love of God, her skulls shimmer and sparkle. Like the Mesoamerican peoples, she viewed death as a celebration rather than a fear, writing in one of her final works: “La Mort n’existe pas. Life is eternal.”