#ChthonicThursday: Eusapia

It might be because of my background in architecture, it might be because it’s fantasy, but Italian intellectuals insist it’s not (which is hilarious when it’s not infuriating), but I’m particularly fond of Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities. Today I give you one of the cities connected with death: Eusapia. If you’re not familiar with it, […]

It might be because of my background in architecture, it might be because it’s fantasy, but Italian intellectuals insist it’s not (which is hilarious when it’s not infuriating), but I’m particularly fond of Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities. Today I give you one of the cities connected with death: Eusapia.

If you’re not familiar with it, the narrative of the book unfolds through a dialogue between the ageing Mongol Emperor Kublai Khan and the Venetian explorer Marco Polo. The book is structured as a series of poetic descriptions of 55 imaginary cities, each representing different themes and reflections on human experience, memory, and identity.

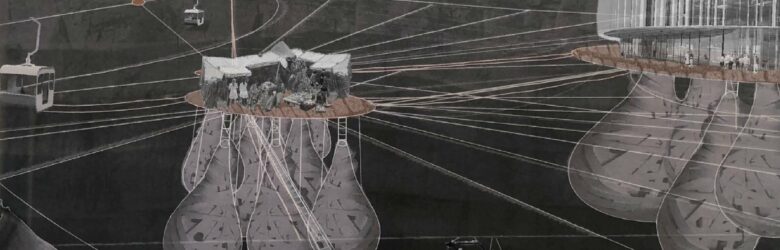

Calvino isn’t in the public domain yet, so what follows is more a retelling than a translation. Enjoy. You can also read it on my Patreon. The picture in the header comes from this project.

No city inclines more naturally to the delights of life and the liberation from care than the city of Eusapia. Its denizens have wrought a faithful replica of their city beneath the earth’s surface to bridge the chasm between life and death with grace and subtlety. Here, in this netherworld, the corpses—preserved in their skeletal integrity as yellowed skin shrinks around their bones—are tenderly carried to continue their earthly pursuits. These souls delight in a realm of carefree revelries: most corpses are arranged around tables heaped with bounty, set in eternal dance, or posed to sound tiny trumpets. Yet, all the vocations and trades of living Eusapia are also enacted below, especially those performed with greater joy than vexation: the clockmaker, surrounded by the silent tick of his stopped clocks, leans his parchment ear against a dissonant grandfather clock; a barber, with his dry brush, lathers the cheekbones of an actor who learns his script through vacant eye sockets; a maiden, with an eternal grin on her skull, draws milk from the carcass of a heifer.

Many of the living, however, yearn for a fate in death that’s different from their earthly toil, or so it seems: the necropolis swells with big-game hunters, mezzo-sopranos, bankers, violinists, duchesses, courtesans, and generals—far exceeding the number the living city ever held.

A solemn brotherhood of hooded figures is charged with the sacred duty of escorting the deceased below and placing them in their chosen station. None other may venture into the Eusapia of the dead; all that is known of the nether city is learned from these brothers.

It is said that a similar brotherhood exists among the dead, ever ready to extend a spectral hand and, upon their death, these hooded brethren are fated to perpetuate their tasks in the nether Eusapia. Whispers abound that some among them have already succumbed to death yet continue their ascent and descent. Regardless, this brotherhood commands great authority within the living Eusapia.

Each descent reveals changes wrought in the lower Eusapia; the dead, it seems, innovate their city with careful deliberation, not capricious whim. From year to year, the Eusapia of the dead evolves beyond recognition. Eager to keep pace, the living aspires to emulate these innovations, as reported by the hooded brothers. Thus, the living Eusapia has become a mirror of its subterranean twin.

It is said this curious cycle is not new: indeed, it was the dead who first constructed the upper Eusapia in the likeness of their city. Rumour has it that, in the twin cities, there is no longer any way of knowing who is alive and who is dead.

The name Eusapia comes from “Eusébeia,” a Greek word that means “Piety, Respect, and Devotion towards the gods.” More specifically, Eusapia literally translates to “she who has true piety.”

It’s highly likely, however, that Calvino chose the name with a hint to Eusapia Palladino, an Italian spiritualist and medium who claimed to be able to communicate with the dead and who was unveiled as a charlatan multiple times throughout her “career”.