Bellini’s Lamentation

The Diocesano Museum in Milan is one of the most interesting realities on the territory, both for its permanent collection and for its habit of organizing temporary exhibitions around one single piece, usually borrowed from a prestigious museum in another city. The depth you require when your exhibition only revolves around one painting always makes […]

The Diocesano Museum in Milan is one of the most interesting realities on the territory, both for its permanent collection and for its habit of organizing temporary exhibitions around one single piece, usually borrowed from a prestigious museum in another city. The depth you require when your exhibition only revolves around one painting always makes it for a very interesting visit with detailed, in-depth explorations. I gave you one example last year with the special exhibition around Beato Angelico’s Childhood of Christ (post 1 here and post 2 here).

This time the focus rests on the Lamentation over the Dead Christ by Giovanni Bellini, coming all the way from the Musei Vaticani, in the context of the whole Pesaro Altarpiece from which it was extracted. Exhibited as part of a pathway through lent and towards Easter (the museum is a religious institution after all), it becomes a broader exploration on grief and suffering through the contribution of four modern artists.

Giovanni Bellini’s Madonnas and Dead Christs

A man constantly in meditation, always striving to evoke the ancient, understand the new and experiment with them both, he was everything they said he was a Byzantine and Gothic artist first, influenced by Andrea Mantegna and Paduan art then, following in the footsteps of Piero della Francesca and Antonello da Messina, and finally even of Giorgione; and yet, he was always himself: warm blood, wholehearted spirit, in full and deep harmony with humanity -the traces of humanity in history and the mantle of nature.

(Roberto Longhi, 1946)

Born in Venice around 1430, Giovanni Bellini was likely the second or third son of the renowned Venetian painter Jacopo Bellini, and he received his artistic training primarily from his father, alongside his elder brother Gentile. The Bellini workshop was a hub for aspiring artists, and Giovanni likely collaborated with other young talents on various projects.

Upon his father’s death in 1470, Giovanni and Gentile took over the family workshop, receiving numerous commissions together: their most notable collaboration was for the Scuola di San Marco, contributing to a vast narrative cycle depicting the story of Noah’s Ark and the Deluge, but Giovanni’s first solo work of note is generally considered a series of Madonnas with the Child, particularly the so-called Greek Madonna currently preserved at the Brera Art Gallery here in Milan.

Giovanni’s early paintings, characterized by sharp details and a focus on perspective, displayed the influence of his father and contemporaries like Andrea Mantegna. They also didn’t shun away from other influences that were very strong in Venice, such as the iconic Byzantine style and the Flemish influence.

During the decade following his father’s death, Giovanni quickly established himself as a leading figure in the Venetian Renaissance. He developed a more personal style, emphasizing soft figures and harmonious compositions, in the wake of Giorgione and Titian’s revolutionary approach to painting. His use of landscape backgrounds became increasingly sophisticated, adding depth and atmosphere to his religious and mythological paintings.

These are all elements that we can find in the Lamentation.

If the landscape is the main character in compositions such as the Transfiguration from the Museo Correr and the Agony in the Garden from the National Gallery, the Madonna Davis comes closer to what we’ll observe in the Pesaro altarpiece, with a set of frames used as a painting inside the painting.

Bellini revisited the themes of Madonna with Child and Christ’s suffering multiple times throughout his career, infusing each rendition with unique gestures, expressions, and arrangements. He introduced variations such as angels or mourners and made significant changes to the iconography with the intention of immersing the viewer in Christ’s suffering.

Starting from the 1960s, Bellini focused more intensely on this theme, originally conceived for private devotional use but later incorporated into Venetian polyptychs. He adapted scenes to a more intimate setting, as exemplified by works like the Dead Christ at the Poldi Pezzoli and the Dead Christ supported by the Madonna and St. John at the Accademia Carrara. These paintings exude profound dramatic tension, blending Mantegna’s austere forms with a poignant portrayal of human suffering.

The culmination of this initial series of depictions is seen in the famous Pietà from Brera, distinguished by its unconventional horizontal format and meticulously crafted composition, which highlights the equilibrium between the substantial presence of the figures, the surrounding landscape, and the portrayal of deeply human and intense sorrow. Mary holds her face close to his dead son’s as if to catch one hint of breath, and John turns his face away to hide his sorrow as if the sight is too much for him to bear.

Hands and landscape also play an important part, with Mary’s bony fingers supporting Christ’s deadweight arm, and a curved road that we can see above her shoulder.

Another masterpiece of the genre is the Lamentation over the Dead Christ in the Uffizi, in which numerous characters are arranged around Christ and express their grief with a variety of expressions and attitudes, revealing Bellini’s ability to renew the iconography to tell a human story of hope and suffering.

Bellini’s quest for painting deep personal feelings in religious scenes of great solemnity reaches its zenith with his preferred subjects, the Pietà and the Madonna and Child.

An encounter with Antonello da Messina during his visit to Venice, between 1474 and 1476, proved to be pivotal for Bellini’s research and development: Antonello could boast a more proficient use of the oil painting technique, a method which allowed for compositions that were more vivid and gentle at the same time and that Bellini already admired in the works of the Flemish masters. He created the remarkable Pesaro Altarpiece in those years of experimentation.

The Pesaro Altarpiece

Created for the main altar of the church of San Francesco in Pesaro, possibly commissioned by the local friars, the Altarpiece is one of Bellini’s masterpieces because of its intricate composition and quality.

Painted in Venice around the mid-1570s, this work is groundbreaking from its structure, as the wooden panel is crafted without the use of nails or metal joints, to facilitate its disassembly and reassembly when transported to Pesaro from the lagoon.

The central panel portrays the Coronation of the Virgin surrounded by Saints Paul, Peter, Jerome, and Francis, while the predella recounts episodes from their lives. Additional figures of saints are depicted on the pillars, enhancing the richness of the composition.

In this central scene, Bellini achieves a newfound solemn grandeur of descriptive naturalism, with figures almost life-size, and a geometric organization of space that reeks Reinassance because of the perspective of the floor, the architectural elements of the throne structure and the geometry of choice for the pedestal.

What’s really original in this work, if compared to Bellini’s earlier polyptychs, is the abandonment of traditional compartmentalization and the choice to assemble the figures in a unified spatial composition. To complement this bold choice, the throne has a window framing the landscape in a “painting within the painting”, featuring a distant hilltop citadel that scholars argue might be the Rocca di Gradara. The scenario is a theological reference to heavenly Jerusalem or to the Turris Eburnea, a symbol of purity coming from Solomon’s Song of Songs later associated with Mary by the 1587 Litany of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

The installation in Milan decides to render credit to the composition by hanging a scaled reproduction of the whole altarpiece and, next to a video with some details, a set of three frames hanging from the ceiling at different heights and different distances: one for the general marble frame separating the Coronation from the Lamentaion, one for the marble structure of the throne and a last one for the window inside the frame, and the landscape it highlights.

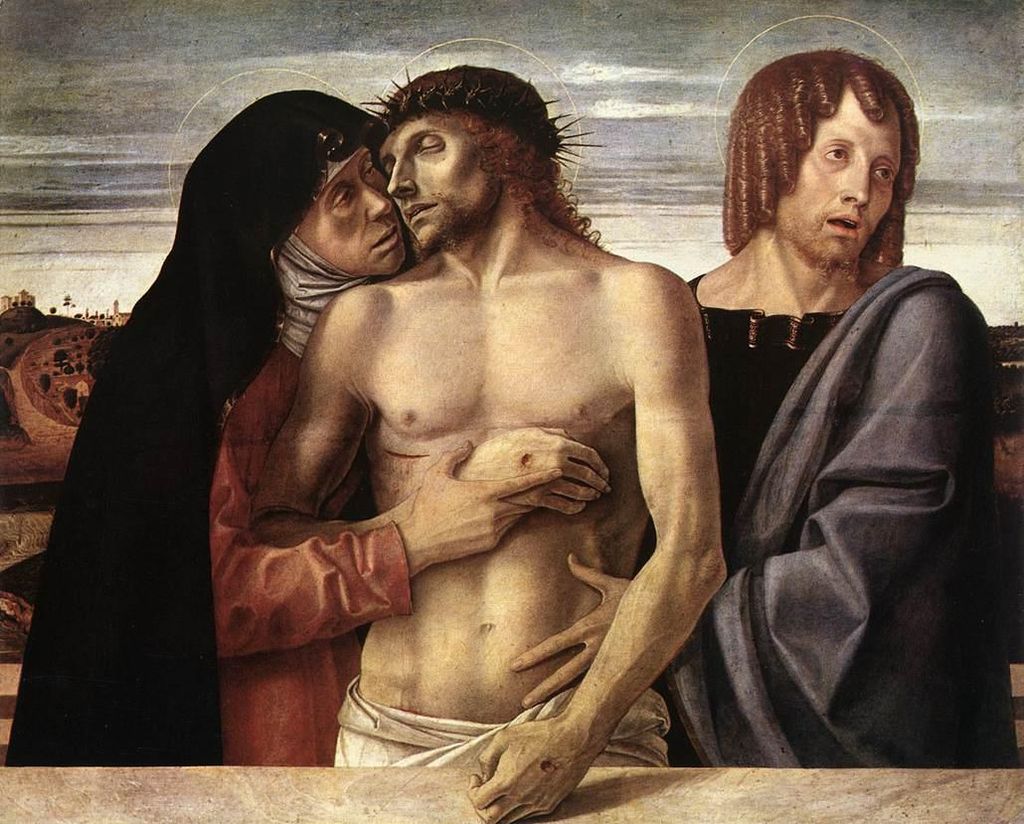

The Lamentation

The last room is dedicated to the Lamentation itself, confiscated as war booty by French troops in 1797 and returned to Italy in 1816 only to be separated from the main work, currently in Pesaro where it belongs.

When observing the painting, you should remember that the actual altarpiece is over 6 meters high, and this makes for some artistical choices: the figures are compressed In a distinctly vertical framing, they are sculptural and foreshortened from the bottom up.

The deposed, exsanguinated Christ is seated on the tomb, his face ashen and his mouth half-closed, his legs wrapped in the white shroud. He is supported by Joseph of Arimathea, attired as a cardinal in red and white robes, whose face is half-hidden and whose beard seems to blend together with the visage of Christ. Joseph, acting as a backrest for the corpse, seems to be assisting the other two figures: Nicodemus, standing on the right, who holds in his hand the jar of balsams, and the kneeling Mary Magdalene, who’s gently anointing his wounds.

As one of the contemporary artists will remark in the closing section of the exhibition, the hands are one of the main characters in creating the emotional tension of a grief that’s expressed with composure.

“After this, Joseph of Arimathea, secretly a disciple of Jesus for fear of the Jews, asked Pilate if he could remove the body of Jesus. And Pilate permitted it. So he came and took his body. Nicodemus, the one who had first come to him at night, also came bringing a mixture of myrrh and aloes weighing about one hundred pounds. They took the body of Jesus and bound it with burial cloths along with the spices, according to the Jewish burial custom.”

– John 19:38-40

Four Contemporary Artists

After the original painting, the return route of the exhibition takes you through four rooms hosting four modern artworks in some way inspired or related to Bellini’s Lamentation.

The four artists in the exhibition are:

- LETIA Letizia Cariello;

- Andrea Mastrovito;

- Emma Ciceri, with a video installation holding the hands of her daughter;

- Francesco De Grandi, with a modern deposition.

LETIA

Possibly the strongest and most powerful piece among the four, the artist works on two themes: one geometrical, and one emotional.

As Bellini’s piece was the cymatium for the altarpiece, this modern artwork consists of two vertically arranged panels connected by hinges: the upper panel, with its pointed arch shape, tilts toward the viewer like Bellini’s figures tilt back in their perspective trick, and strings of red wool are intertwined in patterns, connected in rays, drawing figures and faces and flowers. Square-headed nails are fixed into the background, both connecting the red strings and sticking out raw, unprotected. But the central element, like the window inside a window in Bellini’s altarpiece, is a mirror with a hook, an icon evoking great violence, that’s impossible not to connect to the plight of young women throughout our poor, modern society.

Suspended from the hook is a braid from the artist’s own hair, connecting the iconography to that Magdalene who tended to Jesus’ wounds and was called a whore for her devotion.

Her installation establishes a stringent relationship between the experience of pain and rebirth.

Andrea Mastrovito

Mastrovito decides for a less personal and more political statement, choosing to work on a picture that was taken on 5 March 2022, at the beginning of the war unleashed by Russia against Ukraine, when a wooden crucified Christ was removed from the Armenian Cathedral in Lviv, to be secured in a bunker. The photo was taken by Portuguese freelancer Andrés Luís Alves, and Mastrovito adds multiple layers to the photograph, with frottages from the covers of famous dystopian books and works such as No Exit by Jean-Paul Sartre, Kurt Vonnegut’s Breakfast of Champions, or George Orwell’s 1984.