Who’s afraid of the Great God Pan?

I’ve been reading a splendid and passionate book on the God Pan by Paul Robichaud, and it seems to be perfectly on point with the collective re-reading of The Wind in the Willows we’re doing on Twitter with a group of people. As you might remember, there’s one particular chapter I’m particularly fond of – […]

I’ve been reading a splendid and passionate book on the God Pan by Paul Robichaud, and it seems to be perfectly on point with the collective re-reading of The Wind in the Willows we’re doing on Twitter with a group of people. As you might remember, there’s one particular chapter I’m particularly fond of – Chapter 7 – in which our heroes the Mole and the Rat go out at night looking for a lost baby otter. If you haven’t, I suggest you take a look at this old article I wrote before you proceed.

According to Tolkien, the appearance of the Great God Pan in this story is an overdoing on behalf of Kenneth Grahame, «that addition of an extra colour that spoils the palate». But of course, I don’t agree with him in this instance, though I understand the purity he expects from stories.

Now, there’s one particular passage in the chapter, where the Rat and the Mole come face to face with the divine apparition, and Grahame knows better than to pick words lightly when it comes to Pan.

“Afraid! Of Him? O, never, never! And yet—and yet—O, Mole, I am afraid!”

The connection between Pan and terror is an ancient one, and it had fleeting fortune throughout the centuries.

Among the many epithets for the god, we find Phorbas, “the terrifying one”. According to some sources, it was one of the primary aspects of the god, equally important to Agreus, “the hunter”, and the pastoral Nomios.

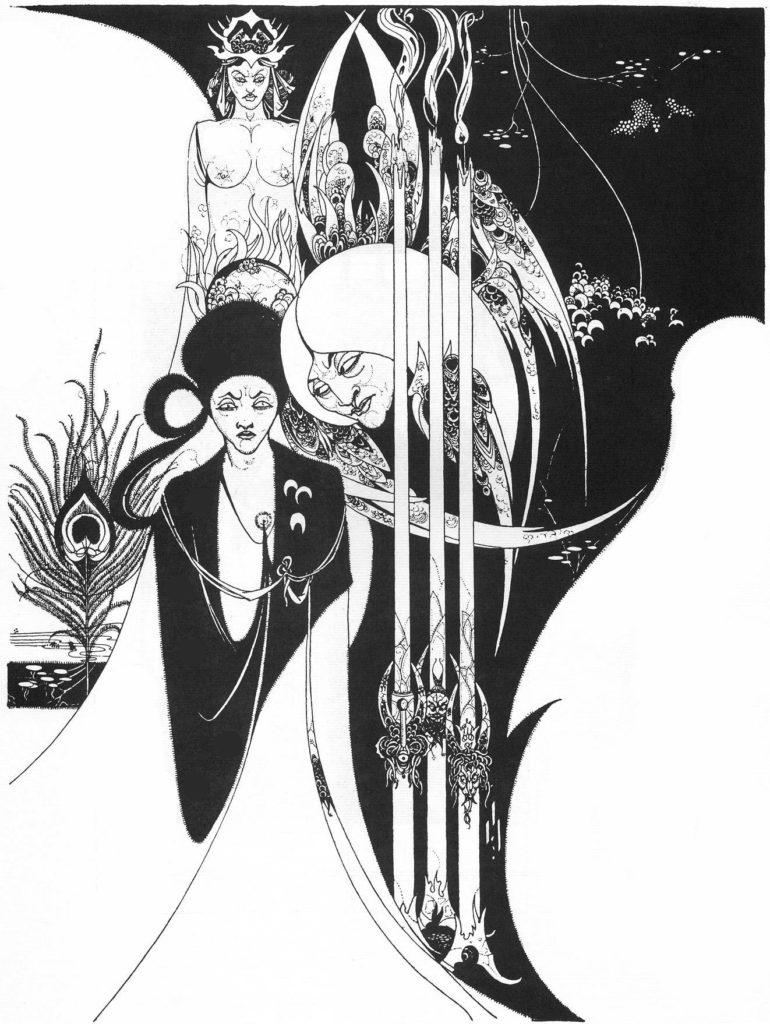

I’m sure you’re all familiar with Algernon Blackwood‘s powerful usage of mythical creatures as a source of horror, as it happens in The Centaur (1911), and the most famous usage of Pan in this way is probably made by his contemporary Arthur Machen in his novella The Great God Pan (1890). Tiptoeing the fine lines between Gothic, fantasy and science fiction, Machen’s novel tells the story of a disturbing woman who’s the source of death and horror to the people around her, and who’s later revealed to be the offspring of the forced encounter between a woman and the god Pan during an occult experiment.

Take Pan, replace it with an extraterrestrial entity, and you have a story by H.P. Lovecraft.

Pan here is given a dark twist, with him representing “intelligence blended with a darker power, deeper, mightier, and more universal than the conscious intellected man”, as S.T. Coleridge put it more than a century before Machen while looking at a strangely horned statue of Moses by Michelangelo.

The same idea will be picked up by John Keats in the Hymp to Pan featured in his Endymion (1818):

O hearkenee to the loud-clapping shears,

While ever and anon to his shorn peers

A ram goes bleating: Winder of the horn,

When snouted wild-boars routing tender corn

Anger our huntsman: Breather round our farms,

To keep off mildews, and all weather harms:

Strange ministrant of undescribed sounds,

That come a-swooning over hollow grounds,

And wither drearily on barren moors:

Dread opener of the mysterious doors

Leading to universal knowledge—see,

Great son of Dryope,

The many that are come to pay their vows

With leaves about their brows!

The German scholar and philologist Wilhelm Heinrich Roscher will be paramount in the definition of this concept and linked Pan to the experience of the nightmare in his Ephialtes: A pathological-mythological treatise on nightmares and the half-demons of classical antiquity (1900 sharp).

But are these phantasies grounded in the original sources? Let’s find out.

Panic in appearance: half-man, half-animal

According to Paul Robichaud in the book I mentioned above, a first reason for terror in confronting the god Pan comes from his hybrid physical features and indeed the first result of the god’s birth was freaking people out.

Though sources give conflicting accounts of his father and all these stories are likely to originate when the Peloponnesian Greeks tried to absorb into their pantheon a pastoral deity born in the Arcadian region, Pindar and the so-called Homeric hymn all agree on one account: when the infant god was born, the first one to see him fled in terror. In the Homeric hymn, the one to flee is his nurse, while his father Hermes laughs at the son’s difformities and takes them as a sign of mischief. He brings the child to Olympus and the gods are equally delighted at his sight, particularly Dyonisus who probably is starting to see some resemblances between him and the goat-footed creature. Both gods in fact are associated with an altered state of mind, have strong connections with feral animals such as the lynx and go around with a retinue of merry women you shouldn’t mess with (nymphs for Pan, and maenads for Dyonisus).

In this sense, it’s interesting how Reinassance and Baroque pick up on Pan’s lively attitude and connect him with another hybrid, half-man, half-bird this time: winged Cupid.

From the Homeric hymn comes the very old but erroneous idea that the name “Pan” is connected to the Greek word “all”. The origin most likely lies in the word “paean”, to pasture, with a play on words with the similar term “opaon”, companion.

Another account, by Aeschylus, runs similarly but shuffles roles and parts: in his story, Pan’s father is Zeus and his mother is the nymph Kallisto. Pindar even claims his father is Apollos. But that’s inconsequential to us.

This particular kind of fear Pan is able to inspire since his birth stems simply from his appearance: by showing a hybrid between man and beast, men are frightened in confronting their own bestiality, while Gods are very well aware of this human side and are simply amused at the god’s clever way of communicating this trait.

According to Plato’s Phaedrus, Socrates was a great advocate of coming to terms with this dual nature: he addresses the god by calling him “dear”, and prays to him that he’ll be able to “become beautiful within”, by reconciling inner and outer worlds so that “what is in my possession outside me may be in friendly accord with what is inside”. Instead of being a god of excess and imbalance, Pan becomes a cosmic symbol of balance, a trait that will often surpass his nature as Phorbas.

Stoic philosophy will wholeheartedly embrace the idea of Pan as the embodiment of all elements and will see the god as an allegory of the universe.

This aspect was also particularly significant in the Orphic cults, which will try to summon the god in number 10 of the 87 surviving hymns. You can read it here, and it’s rather beautiful.

By the end, the poet specifically mentions panic and says (in this translation by Thomas Taylor):

Come, Bacchanalian, blessed power draw near, fanatic Pan, thy humble suppliant hear,

Propitious to these holy rites attend, and grant my life may meet a prosp’rous end;

Drive panic Fury too, wherever found, from human kind, to earth’s remotest bound.

Porphyry, in his De abstinentia, warns that this evocation can be dangerous as many forms of what he starts to call “black magic”: worshippers are most likely to die of fright if the summoning is a success.

If you’re interested in Porphyry and his accounts on magic, as you should be, see here.

Perilous settings: the wilderness

The Homeric hymn also adds another element to the aspect of Pan as a god to be feared, by stressing the connection between his activities (and his cult) and wilderness. People are dancing dangerously close to the edge when worshipping this strange god from Arcadia.

“Through wooden glades

he wanders with dancing nymphs

who foot it on some sheer cliff’s edge“

This aspect is supported by archaeological findings, with a temple of Pan being in a gorge of the River Neda, near Mount Lykaion. and another famous place of worship being a cave near Athens. The most recent discovery of a temple to Pan was made in 2020 at the Nahal Hermon Nature Reserve in current Israel, below a Byzantine place of worship, and I urge you to see for yourself the sheer beauty of that natural setting. You can read about the finding here.

Wolves also constitute a significant bridge connecting the god with a fear of wilderness, and not just only through the geographical proximity with Mount Lykaion: as a protector of herds and a hunting god, it is believed he held some sort of power over packs.

Livy will take this connection further in Roman times, by linking Pan with Faunus and Faunus with Lupercus, the pastoral god celebrated in February with the revelries known as Lupercalia. They were a wolf festival allegedly instituted by the legendary Arcadian leader Evander and Justin himself connects them with Pan in his Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus when he says they were cults of “the Lycaean god, whom the Greeks call Pan and the Romans Lupercus”.

The connection between fear and nature will be furtherly expanded upon by Francis Bacon, who will justify that Pan inspires terror because “nature has implanted fear in all living creatures”.

Inspired Panic

The most powerful way Pan manifests his terrifying trait is by inspiring supernatural and unmotivated fear without even showing himself.

A first account for this particular manifestation comes from the geographer Pausanias in his Guide for Greece where – possibly quoting a lost account by Hieronymus of Cardia – he recounts how the Galatians tried to invade Greece.

They camped where night overtook them retreating, but during the night they were seized by the Panic terror. (It is said that terror without a reason comes from Pan.) The disturbance broke out among the soldiers in the deepening dusk, and at first only a few were driven out of their minds; they thought they could hear an enemy attack and the hoof-beats of the horses coming for them. It was not long before madness ran through the whole force. They snatched up arms and killed one another or were killed, without recognizing their own language or one another’s faces or even the shape of their shields. They were so out of their minds that both sides thought the others were Greeks in Greek armor speaking Greek, and this madness from the god brought on a mutual massacre of the Gauls on a vast scale.

Herodotus gives a similar account in his Histories while writing about the Persian Wars, though his account is most likely derivative.

The story inspired Robert Browning in his 1879 poem Pheidippides.

The most significant account for this behaviour possibly is to be found in Longus’ Daphnis and Chloe, one of the few surviving novels from ancient times.

In the story, fair Chloe is kidnapped by pirates and her betrothed Daphnis, traditionally the inventor of pastoral poetry, prays to the nymphs for help and promises to sacrifice a goat if the woman is saved.

But, when night began to fall and put an end to their enjoyment, suddenly the whole earth appeared in flames: the splash of oars was heard upon the waters, as if a numerous fleet were approaching. They called upon the general to arm himself: they shouted to each other: some thought they were already wounded, others lay as if they were dead. One would have thought that they were engaged in a battle by night, although there was no enemy.

After a night thus spent, a day followed even more terrible to them than the night. They saw Daphnis’s goats with ivy-branches, loaded with berries, on their horns: while Chloe’s rams and ewes were heard howling like wolves: Chloe herself appeared, crowned with a garland of pine. Many marvellous things also happened on the sea.

When they attempted to raise the anchors, they remained fast to the bottom: when the oars were dipped into the water to row, they snapped. Dolphins, leaping from the waves, lashed the ships with their tails, and loosened the fastenings. From the top of the steep rock overhanging the promontory was heard the sound of a pipe: but the sound did not soothe the hearers, but terrified them, like the blast of a trumpet.

Then, smitten with affright they ran to arms, and called upon their invisible enemies to appear: after which, they prayed for the return of night, hoping that it might afford them some relief. All who possessed any intelligence clearly understood that all the marvellous things that they had seen and heard were the work of God Pan, who was angry with them for some offence they had committed against him: but they could not guess the cause of it, for they had not plundered any spot that was sacred to him.

At last, however, at mid day, when their general had fallen asleep, not without the intervention of the Gods, Pan himself appeared to him and spoke as follows:

“O most impious and sacrilegious of men! what has driven your frenzied minds to such audacity? You have filled with war the country that I love, and have carried off the herds of cattle and flocks of sheep and goats entrusted to my care: you have dragged away from my altars a young girl whom Love has reserved for himself, to adorn a tale. Nay, you did not even respect the presence of the Nymphs, nor me, the great God Pan. Wherefore you shall never again see Methymna with such booty on board, nor shall you escape this pipe, which has so smitten you with alarm: I will swamp you in the waves and give you as food to the fishes, unless you speedily restore Chloe and her flocks, sheep and goats, to the Nymphs. Arise then, put ashore the young girl with all that I have mentioned: and then I will guide your course by sea, and Chloe’s by land.”

A translation of the work can be found here.

Pan is represented by Marc Chagall in one of his 42 coloured lithographs illustrating the story.

Interestingly enough, the connection between Pan and the sea is not unheard of: according to Philippe Borgeaud, Pan Aktios was venerated by fishermen as the god of sea promontories and the connection might be found in how the goats are fond of salt.

The episode might also be an echo of a similar story in which Dionysus is kidnapped by sailors while disguised as a boy, and he breaks havoc on them as punishment.

Daphnis and Chloe is a very influential work and will inspire three operas, one famous ballet and two movies.

Not all of them feature Pan’s direct intervention, but many of them try to incorporate the god in one way or the other.

Joseph Bodin de Boismortier was the first one to adapt the story to music and wrote a pastorale in 3 acts in 1747. It’s his Op. 102.

If you’re curious about it, I suggest you read it here.

You can listen to it and see the score here.

Another pastorale heroïque was written by Jean-Jacques Rousseau (yes, he also wrote music) between 1774 and 1776, but he died in 1778 and he never finished. One can only guess what kind of philosophical significance he would have embued the story with.

Jacques Offenbach‘s 1860 one-act opérette, inspired by a theatrical adaptation of the original novel performed at the Théâtre du Vaudeville in 1849, sees Pan interpreted by a bass and the original performer in the March 27th premiere was Amable “Désiré” Courtecuisse, who will also play the part of Jupiter in the 1874 Orpheus in the Underworld.

In this opérette, Pan is not so much a helper and is introduced as an element of tension: Daphnis insults him and he scorns the lovers, trying to win Chloe for himself. The resolution comes fortuitously, as the lascivious god accidentally drinks a sip of water from river Léthée and forgets all about his intent to pursue Chloe. Below you can see a reinterpretation by the Cambridge Youth Opera.

The ballet was composed in 1912 by no other than Maurice Ravel, for no other than Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, and it was choreographed by that same Michel Fokine who worked on the solo dance The Dying Swan for Anna Pavlova from the highly influential last piece in Camille Saint-Saëns’ Carnival of the Animals. The set was designed by Léon Bakst and it must have been absolutely stunning.

The ballet, or symphonie choréographique as it’s preferably referred to, is far more faithful to the original novel, if compared to what Offenbach decided to do, and its strikingly impressionistic features are exemplified by the way both Nymphs and Pan are represented as outlines in the background, melting with the natural scenery, and come to life at night in a manifestation of the uncanny.

Pan in particular is invoked when pirates abduct unsuspecting Chloe, at the end of Part I.

Part II is the most powerful in this sense: at the pirates’ camp, Chloe is repeatedly forced to dance for her abductors, and frightening satyrs manifest just when she’s about to be violated by their leader.

The whole ballet with the score can be listened to here.

The passages where Ravel confronts himself with the uncanny manifestation of the supernatural are the Danse lente et mystérieuse des Nymphes, at the end of Part 1 as I was saying, and the end of Part 2. Most of these musical pieces will feature in what’s commonly known as Suite n.1, Fragments symphoniques de ‘Daphnis et Chloé’ (Nocturne—Interlude—Danse guerrière) developed by Ravel himself around 1911.

Panic through music

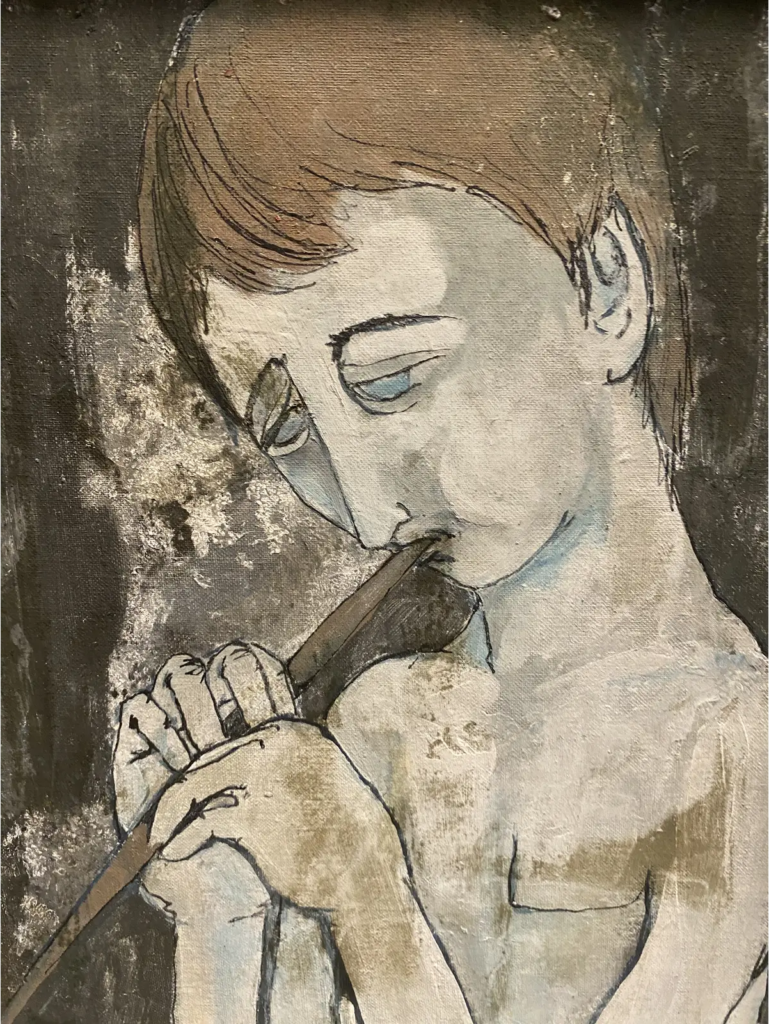

Though Pan’s ability to instil fear often doesn’t need any prompt, one shouldn’t forget his connection with music. The story of how he created his famous flute from reeds is well-known in Ovid‘s retelling: while pursued by the horned god, the nymph Syrinx was transformed into a reed on the banks of the River Ladon. While clutching what was left of the object of his desire, the reeds whistled with a haunting sound and Pan vowed to create a musical instrument out of her body. Objectification at its best.

Theocritus is probably the first to connect Pan, fear and music in one of his Idylls, when the shepherd Thyrtis refuses to play his flute and says:

No, no man; there’s no piping for me at high noon.

I go in too great dread of Pan for that.

Virgil is possibly the one who took the musical aspects of Pan to absolutes. He however also adds interesting features in his Eclogues, by showing us a Pan with vermillion pigments smeared on his face.

Pan came, Arcady’s god, and we ourselves saw him,

crimsoned with vermilion and blood-red elderberries.

Talk about freaking out.

The same Porphyry connects Pan with danger through music. As Eusebius quotes, he states nine people were found inexplicably dead and, when summoned, Apollo’s oracle stated this to be the cause:

“Lo! where the golden-horned Pan

In sturdy Dionysos’ train

Leaps o’er the mountains’ wooded slopes!

His right hand holds a shepherd’s staff,

His left a smooth shrill-breathing pipe,

That charms the gentle wood-nymph’s soul.

But at the sound of that strange song

Each startled woodsman dropp’d his axe,

And all in frozen terror gaz’d

Upon the Daemon’s frantic course.

Death’s icy hand had seiz’d them all,

Had not the huntress Artemis

In anger stay’d his furious might.

To her address thy prayer for aid.” ‘

As death befalls any mortal witnessing the true form of a god, we might as well argue that music is the true manifestation of Pan.

Music brings us back to the Wind in the Willows too: the Mole and the Rat promptly forget seeing Pan, but a lingering music brings them back to the sweet sorrow of having been blessed and forgot about it.

Lest the awe should dwell—

And turn your frolic to fret—

You shall look on my power at the helping hour—

But then you shall forget!—forget, forget—

Lest limbs be reddened and rent—

I spring the trap that is set—

As I loose the snare you may glimpse me there—

For surely you shall forget!Helper and healer, I cheer—

Small waifs in the woodland wet—

Strays I find in it, wounds I bind in it—

Bidding them all forget!

The ultimate terror: a dying god

There’s another kind of fright that Pan can inspire, and probably one that will strike our modern minds more: Pan is the only ancient god who eventually dies. In his De Defectu Oraculorum, Plutarch recounts this terrifying event and swears that one Epitherses…

…designing a voyage to Italy, he embarked himself on a vessel well laden both with goods and passengers. About the evening the vessel was becalmed about the Isles Echinades, whereupon their ship drove with the tide till it was carried near the Isles of Paxi; when immediately a voice was heard by most of the passengers (who were then awake, and taking a cup after supper) calling unto one Thamus, and that with so loud a voice as made all the company amazed; which Thamus was a mariner of Egypt, whose name was scarcely known in the ship. He returned no answer to the first calls; but at the third he replied, “Here! here! I am the man.” Then the voice said aloud to him, “When you are arrived at Palodes, take care to make it known that the great God Pan is dead.”

Epitherses told us, this voice did much astonish all that heard it, and caused much arguing whether this voice was to be obeyed or slighted.

Thamus, for his part, was resolved, if the wind permitted, to sail by the place without saying a word; but if the wind ceased and there ensued a calm, to speak and cry out as loud as he was able what he was enjoined.

Being come to Palodes, there was no wind stirring, and the sea was as smooth as glass. Whereupon Thamus standing on the deck, with his face towards the land, uttered with a loud voice his message, saying, “The great Pan is dead.”

He had no sooner said this, but they heard a dreadful noise, not only of one, but of several, who, to their thinking, groaned and lamented with a kind of astonishment. And there being many persons in the ship, an account of this was soon spread over Rome, which made Tiberius the Emperor send for Thamus; and he seemed to give such heed to what he told him, that he earnestly enquired who this Pan was; and the learned men about him gave in their judgments, that it was the son of Mercury by Penelope. There were some then in the company who declared they had heard old Aemilianus say as much.

Christian chronicles are of course delighted with this news and initially link Pan’s death with Christ exorcising all demons and false gods (see Eusebius, who draws this conclusion from the erroneous idea that Pan means “all”).

Oddly enough, later scholars will come to identify Pan with Christ, but that’s a different story.

For now, is there anything more terrifying than such a powerful creature consumed and fading away?