Pool of Tears

It took me three Sundays to get here, between falling Alices, psychedelic corridors, glass tables, drink-me bottles and eat-me cakes. Today we properly step out from chapter 1, even if we already did that (the scenes where Alice grows up are, in fact, in Chapter 2). At the beginning of Chapter 2, we see the […]

It took me three Sundays to get here, between falling Alices, psychedelic corridors, glass tables, drink-me bottles and eat-me cakes. Today we properly step out from chapter 1, even if we already did that (the scenes where Alice grows up are, in fact, in Chapter 2).

At the beginning of Chapter 2, we see the Rabbit again and this time he doesn’t just have a waistcoat: he’s «splendidly dressed, with a pair of white kid-gloves in one hand and a large fan in the other». We also hear mention of a character that’s not particularly popular, mostly because she not included in the cartoon: the Duchess.

“Oh! The Duchess, the Duchess! Oh! Wo’n’t she be savage if I’ve kept her waiting!”

Unfortunately the rabbit drops gloves and fan, a detail some artist decide to consider while they show us the grown-up Alice, and off he goes again.

When it comes to the Rabbit, Carroll himself writes that he’s portrayed as the parody of an adult, in contrast with Alice’s untamed youth.

And the White Rabbit, what of him? Was he framed on the “Alice” lines, or meant as a contrast? As a contrast, distinctly. For her “youth,” “audacity,” “vigour,” and “swift directness of purpose,” read “elderly,” “timid,” “feeble,” and “nervously shilly-shallying,” and you will get something of what I meant him to be. I think the White Rabbit should wear spectacles. I am sure his voice should quaver, and his knees quiver, and his whole air suggest a total inability to say “Bo” to a goose!

In the first version of the story, Alice’s Adventures Under Ground, the rabbit drops a nosegay, which is the name of a small flower bouquet which name comes from fifteenth-century Middle English and literally means “ornament to appeal the nostrils”. Alice would shrink after smelling those flowers, thus introducing another sense that’s not taste into the size-changing business. I wouldn’t have minded that: the final solution is far less charming.

The scene sometimes gets blended with other scenes I already showed you and I don’t want to give them too much attention, as they’re rarely interesting, but it’s worth mentioning those in which we start to see already the pool of tears. One of them is Peter Newell‘s 1901 edition, with those characteristic full plates in monochrome you should start to recognise by now.

The rabbit doesn’t look particularly fancy, with those trousers, but Alice sure looks nice.

Another one of them is Millicent Sowerby‘s 1907 edition. She was one of the earliest women to illustrate Alice: did I mention that?

By the end of World War I, A.E. Jackson was also illustrating a runaway rabbit and a crouching Alice. His masterpiece, however, is the scene with the rat (later on).

The edition he illustrated is available here. Beware of the kindle option, because (as it often happens with illustrated editions of classic works) it jumps to another completely unrelated book.

Since the white rabbit is described as quite fancy, it’s also worth showing some pictures of him.

I particularly like this one by Gwynedd Hudson, who did an illustrated edition in 1922. You can find a selection of editions illustrated by her, in different conditions, at this address.

The Little Crocodile

As the rabbit wanders off, Alice has the first proper identity crisis of the book and wonders whether she’s still the same of she changed into someone else. In the original manuscript, she wonders whether she’s changed into one of Alice Liddell’s cousins, Gertrude and Florence, while in the final version of the book the names are Ada and Mabel, and we have zero idea who those might be.

In order to be sure she’s herself, she tries remembering stuff she really doesn’t know (like geography, and we also get one of the first math tricks from Charles Dodgson, Lewis Carroll’s mathematician real-life alter-ego). At the end, she gives us the first nursery rhyme of the book.

How doth the little crocodile

Improve his shining tail,

And pour the waters of the Nile

On every golden scale!How cheerfully he seems to grin,

How neatly spreads his claws,

And welcomes little fishes in,

With gently smiling jaws!

This is of course another rhyme Alice gets wrong, like the math calculations and the geography questions.

With very few exceptions, lots of the poems and rhymes in Alice are parodies of songs or poems that a reader in the Victorian Era was bound to know very well and that now have been mostly forgotten. For this particular one, Carroll chooses to make fun of a poem by Isaac Watts, a popular hymn writer and theologian. His work is highly moralistic and, as such, the perfect target for Carroll’s well-placed humour: he takes his poem “Against Idleness and Mischief”, featured in a collection called Divine Songs for Children (1715), and replaces the busy bee – a positive symbol of labour – with the predatory crocodile.

How doth the little busy bee

Improve each shining hour,

And gather honey all the day

From every opening flower!How skillfully she builds her cell!

How neat she spreads the wax!

And labours hard to store it well

With the sweet food she makes.In works of labour or of skill,

I would be busy too;

For Satan finds some mischief still

For idle hands to do.In books, or work, or healthful play,

Let my first years be passed,

That I may give for every day

Some good account at last.

You can almost feel how big Carroll’s «fuck you» is resounding in his “little crocodile”.

At this point, poor Alice is convinced she’s Mabel, because she remembers the words of the song, and she’s even more sad, because apparently Mabel lives in a «poky little house», with «no toys to play with» and «ever so many lessons to learn». Having grown up in size, Alice is here afraid she has grown up in age as well. And decides she’s not going to take that bullshit: she’ll stay underground forever, if she has to.

The little crocodile is not a proper character, but lots of illustrators decided to try their hands at it.

One of the first has to be Charles Robinson, showing us a wonderful crocodile, with his nose above the water as crocodiles do, and through the water we can see the lower part of his jaw opening for the poor fish. You also have to appreciate the strokes in the background, with the palm telling us it’s a proper Nile crocodile.

In 1912, the crocodile was illustrated by Charles Folkard for Songs from Alice in wonderland and Through the looking-glass. The rhymes were put to music by Lucy E. Broadwood and you can find a reprinted edition here. The crocodile is gently drawn with ink while he’s taking care of himself.

There’s also another drawing of him swimming and catching those little fishes.

It is also the case for The Golden Age of Poetry, written and illustrated by Joan Walsh Anglund in 1959.

This website features all the decorated letters, the cover and some colour plates from the interiors, including the full plate with our little merry crocodile.

Russian illustrator Evgeny Shukaev also did a scene with the crocodile and you can find a large collection of his illustrations on this website (also in Russian). He unfortunately gets confused with a gymnast and I wasn’t able to find out much about him, aside from the fact that his work was included in a 1979 edition for which he also designed the cover. Oddly enough, the scan on the Russian website are from a book in English, so I really should be able to find more about it. I love how the crocodile, fancily dressed, also gets to be the ornament for the chapter head.

The regular swimming crocodile is also very nice.

The most important of contemporary authors, however, is probably the surrealist artist Leonora Carrington, who in 1998 made a painting, a bronze sculpture and an urban-sized sculpture based on the poem. There’s a nice article on her here.

Among contemporary and surrealist work, the poem was also included by Edward Blishen in his Oxford Book of Poetry for Children, richly illustrated by Brain Wildsmith in an edition you can admire here, on an incredible website dedicated to the life and work of this incredible artist. In the collection, meant as an introduction to poetry for children, there’s stuff from William Blake and Thomas Heywood, William Wordsworth and Thomas Dekker.

It’s not uncommon for the poem to feature in collections and such. Another brilliant example is Because a Fire Was in My Head: 101 Poems to Remember, by Michael Morpurgo, featuring incredible illustrations by Quentin Blake. You can see it here. That crocodile is not well.

That’s also the case for Gyo Fujikawa‘s A Child’s Book Of Poems (1969), which can be read freely here.

Fujikawa was an American illustrator and author, she published in dozens of languages and wrote more than 50 books for children. As an illustrator, she’s recognized as the first illustrator to include children of many races and colours in her work, at least when it comes to mainstream illustrations. She was born in Berkeley, California, from a Japanese family and her name is a masculine one, after Emperor Yao for which her father had a great admiration. If you want to take a look at her most unconventional work, I suggest you look for the 1997 32¢ “yellow rose” stamp and the stamp designed in commemoration for Treaty of Amity and Commerce between Japan and the United States.

The crocodile is not my favourite illustration in the book and is far from being my favourite illustration from her. I strongly suggest you check out her other works before you judge.

More recently, an MFA student in New Media Design at the Rochester Institute of Technology did a lettering and illustration project with the little crocodile: her name is Emma Hsieh and you can find her work here.

Rodney Matthews (and we’ll see his mouse in a while) also did a beautiful crocodile framed in a circle, to pair with an equally beautiful caterpillar.

Another good one is this one by Sherry Trial, a wonderful watercolour with gold leaf. I love the crocodile but, most of all, I love the lettering and the background with the golden sand and the Nile waves.

The artist is from Pennsylvania and on the website you can find many more of her works on auction.

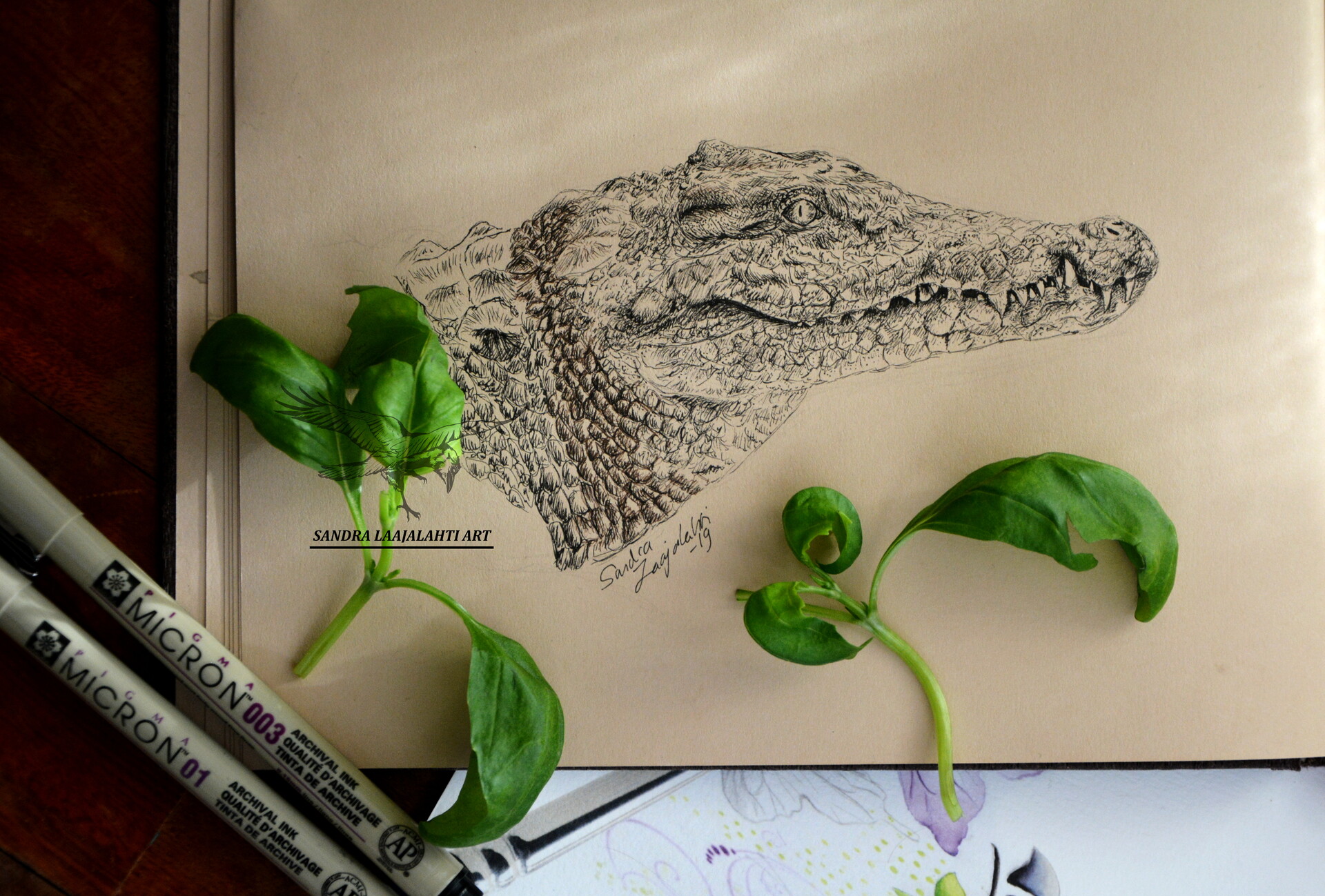

This crocodile by Sandra Laajalahti is also very interesting. I’m not sure about the year, but it might be between 2019 and 2020. Check out her other work too.

One of the most recent works has to be this drawing by Cory Godbey, where we see the crocodile engaged in a bit of self care and improving his shiny tail. On the linked page, he also gives us the preliminary sketches and the whole process. It’s awesome, check it out. There are also some other sketches here.

Scenes from a Victorian Beach

Unlike what happens in many versions, Alice shrinks down again for no particular reason other than being fanning herself with the rabbit’s fan. And since she has been crying for quite a while, she finds herself up to her chin in salted water.

Her first thought is that she has fallen into the sea, and she’s not particularly upset by this thought, as every Londoners knows that if you go to the seaside you can always come back by train.

One of the most interesting portions of the tale, is Carroll’s description of the beach and, particularly, the mention of bathing machines.

According to Martin Gardner in his Annotated Alice, bathing machines were small locker rooms on wheels that were drawn into the sea by horses until the bather was where he wanted to be, so that he could emerge through a door facing the sea and no one would see him. A big umbrella on the back of this contraption would furtherly enhance privacy.

This quaint Victorian contraption was invented about 1750 by Benjamin Beale, a Quaker who lived at Margate, and was first used on the Margate beach. The machines were later introduced at Weymouth by Ralph Allen, the original of Mr. Allworthy in Fielding’s Tom Jones. In Smollett’s Humphry Clinker (1711), a letter of Matt Bramble’s describes a bathing machine at Scarborough.

Since sometimes you would need an annotated edition to read Gardner’s notes, here’s a walkthrough:

- a Quaker is a member of a particular religious sect, born after the English Civil War as a dissent towards the Church of England;

- Ralph Allen (1693 – 1764) was an entrepreneur who reformed the British postal system and was the model for a character in the novel Tom Jones by Henry Fielding;

- Henry Fielding (1707 – 1754) was a British satirist and playwright: Tom Jones is his most famous work;

- The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling is a picaresque novel published on 28 February 1749 and considered one of the first works you can actually define a novel;

- The Expedition of Humphry Clinker is the last picaresque novel by Tobias Smollett, published in London on 17 June 1771: it’s an epistolary novel in which humour arises by the radically different depictions that the six main characters give of the very same events;

- Tobias Smollett (1720 – 1771) was a Scottish author who was greatly influential to Charles Dickens himself.

Walley Chamberlain Oulton, an Irish playwright and theatre historian, describes bathing machines in his 1805 The Traveller’s Guide; or, English Itinerary as a contraption strictly for female bathing:

…four-wheeled carriages, covered with canvas, and having at one end of them an umbrella of the same materials which is let down to the surface of the water, so that the bather descending from the machine by a few steps is concealed from the public view, whereby the most refined female is enabled to enjoy the advantages of the sea with the strictest delicacy.

The Pool of Tears

As Alice soon finds out, and as we already know because of the spoiler in the title, she’s not in the sea at all: she’s in her own tears.

However, she soon made out that she was in the pool of tears which she had wept when she was nine feet high.

Charles Robinson, which I like a lot, indulges quite a bit on the scene, both with small illustrations and full plates. He gives us a fierce crying Alice, which looks like she’s about to wreck havoc, and in the frame ornaments you already see the mouse. He also gives us a swimming Alice and, later, quite a few takes on the mouse.

When it comes to the Pool of Tears, however, the lion’s share is elsewhere due. In 1969, Salvador Dalí (yeah, that Dalì) did 12 illustrations based on Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, one for each chapter plus the cover. You can see all of them here, for instance, and read their publication story (if you know Italian or you know how to use Google Translate). One of the most famous is probably The Pool of Tears, alongside the Caterpillar and the Rabbit’s House.

It doesn’t get any trippier than that.

Going back to a more traditional style, in 1898 Peter Weevers illustrated his edition for Hutchinson and here it is, our Alice crying on top of an already pretty consistent pool. In this situation, the illustrator chooses to focus on her reflection and does a kick-ass job at that.

In 2000, a West German-born American artist named Kiki Smith also approached the subject. One of her works on Alice is preserved at the Museum of Modern Arts and can be seen on-line here. She chooses to show us Alice in a very dark water, almost floating like a cadaver, with more than one huge rat swimming towards her. Now that’s what I’m talking about when I say that I do not appreciate sugar-coated smiling Alices.

The MOMA also preserves a less recent illustration, by Marie Laurencin, a French painter and printmaker, and prominent figure in the Parisian avant-garde as a member of the Cubists, particularly the Groupe de Puteaux. She worked on Alice for a 1930 edition, and here you can see one of the six lithograph she did: the Pool of Tears.

More recent illustrations include Camille Nawrocki‘s full page start of chapter 2. You can find it here and from that page you can see she was working on a project for the whole book. Her DeviantArt profile features eleven illustrations in this particular gallery, but I would say that this one is the most beautiful.

Around 2010, or maybe earlier, another incredible contemporary artist worked on Alice and gave us some of the most beautiful illustrations ever. The name of the artist is Poonam Mistry, traces of these illustrations are both here on the artist’s weblog and here on this blog about children’s books and illustrators.

«Being brought up surrounded by Indian fabrics, paintings and ornaments have heavily influenced my work. Folklore tales and stories of Hindu Gods and Goddesses have been a rich source of inspiration in a number of my illustrations.»

(Poonam Mistry)

The illustration of Alice crying is beautiful, but I also like a lot the summary of chapter 2, with the running rabbit and his fan, the crocodile and again Alice, trying to make sense of it all. Aren’t they amazing?

The Mouse

While she’s swimming in her own tears, and fearing she might drown, she hears a splashing sound and we meet our second actual character (remember that all other characters so far are either in Alice’s imagination or simply people we hear mention of).

she soon made out that it was only a mouse, that had slipped in like herself.

The question of language is almost never an issue, in Alice: she admits herself that the odd thing about the white rabbit is not so much the fact that he talks, but the fact that he has a waistcoat and a pocket watch. However, here Alice makes an effort to speak as it’s proper to speak to a mouse, and she does so by addressing him multiple times. In Carroll’s own words, it’s a joke that comes from a Latin grammar or something and quite an effort was made by scholars to figure out what the heck he’s going on about.

“O Mouse, do you know the way out of this pool? I am very tired of swimming about here, O Mouse!” (Alice thought this must be the right way of speaking to a mouse: she had never done such a thing before, but she remembered having seen, in her brother’s Latin Grammar, “A mouse—of a mouse—to a mouse—a mouse—O mouse!”)

According to a 1975 article called “In Search of Alice’s Brother’s Latin Grammar”, Selwyn Goodacre thought he had found it: it might have been The Comic Latin Grammar (1840), anonymously written by Percival Leigh and illustrated by John Leech. Are you familiar with the Handmaid’s Tale and the whole Nolite te bastardes carborundorum joke? It’s that kind of things. Carroll owned the book, apparently. You can read more research by Goodacre at this address.

The mouse, however, doesn’t answer and Alice tries French, wondering that if it’s a French mouse he must have come over England with William the Conqueror.

So she began again: “Où est ma chatte?” which was the first sentence in her French lesson-book.

Où est ma chatte means “where’s my cat”, and that certainly earns the mouse’s attention. Unfortunately, this also means they start talking about liking or not liking cats, or dogs, completely oblivious of the fact that they’re swimming around in a salty pool and it would be good to find a way to get out of it.

As I was saying, Charles Robinson is also one who seems to be very fond of this mouse, in his 1907 illustrations: he has two full plates, one with a regular frame and another one with decorations, and a small sketch.

The Mouse gave a sudden leap out of the water.

Harry Rountree, the kiwi-born English illustrator who worked on Alice in 1908 for a Thomas Nelson edition, also gives us this scene in full colour: a scared rat jumps out of the water at the mention of cats. He keeps an indoor setting, with both lanterns and windows resembling some underground sewer or cellar, and it’s rather cold and dirty just to look at it.

Do you remember A.E. Jackson from the 1914 edition? I promised you he had a good jumping rat, didn’t I? Here it is.

He’s not so good with the water, or at least he chooses not to go murky like other artists, but I still find it particularly enchanting and it’s probably one of my favourites for this scene.

Charles Robinson, on the other hand, also gives us a rather cinematic illustration with the rat bolting away towards the shore, after a tiny one with the profile of the rat just in case we don’t know how a rat looks like.

Jumping to more recent times, do you remember Evgeny Shukaev?

He too does a crying Alice and a swimming mouse with very large and familiarly-looking round ears.

Another interesting depiction of Alice and the rat swimming is this one, credited to Emily Carew Woodard.

She’s a Cornish artist who has a thing for anthropomorphic animals.

«Both my rural upbringing and my current urban life inspire my work. The romance and deep, rich histories from bygone times are woven into the fabric of my paintings. Artists that have inspired my style are Edward Gorey, Edmund Dulac, Arthur Rackham, William Morris, and writers such as Beatrix Potter and Roald Dahl are undeniable influences on my daily work.»

(E.C. Woodard)

She worked on Alice for the 2015 anniversary, like many many others.

Other recent illustrators include people who did not forget that Alice was shrinking down, therefore the rat must be a huge rat.

It’s the case of Maja Kwiatkowska, with this 2018 watercolour. I don’t like Alice, she’s too Disney for my taste, but I certainly like the take on the rat. That’s one fat rat.

The gallery of the artist seems to be here, though there’s some confusion with the name and a double account.

There was also a beautiful illustration by one Odessa Sawyer, on DeviantArt, but she seems to have erased her account and there’s only trace of it on fucking Pinterest, so I don’t have any source nor any information.

An artist by that name can be found here, the style might be hers, but she doesn’t credit any Alice in Wonderland work in her cv.

If you want to have a laugh, however, I suggest you take a look at this very athletic mouse by Rodney Matthews, done back in 2008 for a collector’s edition. He’s attired as one of those Victorians in the bathing machines and he’s aiming for the Olympics.

More Animals

For some reason, this is the moment where the pool starts to get crowded and we talk about a shore, even if we were in the hallways just few pages ago.

It was high time to go, for the pool was getting quite crowded with the birds and animals that had fallen into it: there was a Duck and a Dodo, a Lory and an Eaglet, and several other curious creatures.

But these are all creatures for next week. And we’ll finally get to the first proper illustration Arthur Rackham gives us. Or had you forgotten that we had started from him?