Rackham’s Peter Pan (1)

I’m not a fan of Peter Pan. My significant otter is quite fond of the Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up, but I kind of hate the little shit and I have always rooted for the pirates. When it comes to adaptations, my distaste expands indifferently to the cartoon and to movies alike, including Hook, and […]

I’m not a fan of Peter Pan. My significant otter is quite fond of the Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up, but I kind of hate the little shit and I have always rooted for the pirates.

When it comes to adaptations, my distaste expands indifferently to the cartoon and to movies alike, including Hook, and I think Once Upon a Time (yeah, the tv series) really started taking a dive for the worst when they introduced that story-arc. A significant exception that I can’t quite explain was the 2003 movie, and not just because it had Jason Isaacs in it (though I’ll admit that if I have vague hopes for the upcoming one it is just because of Jude Law). Apparently, I’m far from being alone in this: read this “Why the 2003 Peter Pan movie is the only one we’ll ever need”.

Anyway, my profound distaste for the mainstream novel does not apply to its “prequel”, the 1902 novel The Little White Bird which was later adapted into Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens. On the contrary, I remember being deeply in love with it since I was a child and I cannot help but placing next to A Midsummer Night’s Dream when it comes to depicting the world of faeries.

Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, as I was saying, is a 1906 re-edition of some chapters from a previous novel, in which J.M. Barrie had put lots of social satire and with extremely dark tones too. The book was published both in the United Kingdom and in the United States, respectively by Hodder & Stoughton, in London, and serially in the monthly Scribner’s Magazine by the homonymous publisher based in New York City. While its 1906 edition solely focuses on the adventures of a little child who lives with faeries in Kensington Gardens, a child who will later become the boy Peter Pan with no explanation and no continuity whatsoever, the original The Little White Bird included the narrator’s adventures in other parts of London and is basically an episodic novel, with Peter’s episodes taking up more than half of it and turning out to be a proper “book within the book”. The story was not received unwell but didn’t have much success either.

It was only after the great success of the play featuring Peter Pan and Wendy, in 1904, that Barrie’s readers wanted more and his publishers re-worked on The Little White Bird in order to extract the portions the public was most likely to read with interests. Little did they care about the fact that Neverland’s and Kensington’s Peter share very little. Nevertheless, the 1906 edition was called Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, and it was illustrated by Arthur Rackham. As I was saying here, it’s one of the works for which he was most praised and still remains one of the most famous and iconic sets of plates. In 1912, Rackham came back to work on his illustrations and a revised edition was issued, with some reworking on the colored plates and 9 additional black and white drawings.

Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens is, as I was saying, really an extraordinary work and wherever it lacks in plot, it certainly makes up for in atmosphere.

In writing about it, my main sources will be Maria Tatar‘s The Annotated Peter Pan, which mostly focuses on the main tale but has a couple of very well-done essays at the back, focusing on the prelude story and on Rackham’s illustrations.

There’s also some useful stuff in Humphrey Carpenter’s Secret Gardens, a book I have used a lot in my Wind in the Willows series, but it focuses more on the play and its relationship with the other novels.

You can basically group the tale around three sets of creatures: birds, fairies, and children. We find lots of situations and ideas Barrie later reused in the play and its related novel, such as the power of imagination and belief, the nonsensical approach, and the way gloomy and dark subjects are treated without any care, with the cruelty only a child could have.

Since Rackham did a shitload of illustrations, I’ll have to split this into several parts, and let’s start from the less obvious part: birds.

Birds

The first group of characters we have to make our acquaintance with is birds because, if you recall from the title of the original novel, the main character himself is linked to them. As Barrie puts it, all children are half-birds, at least at their birth, and Peter is seven days old, so he perfectly qualifies.

Being part-bird, allows children to fly: that’s how Peter is able to escape from his nursery through an open window, and this is how Barrie introduces us to one of the main themes in the following play. Flight is a symbol of freedom from rules and impositions of society, of a carelessness that is even able to surpass the laws of nature: Peter doesn’t care about the conviction that humans can’t fly and, in not caring, he’s able to do so.

On the other hand, Peter takes flight upon hearing his parents discuss his future and here we have the first introduction of what’s probably the main theme in both versions of Peter Pan: the rebellion against the obligation to grow up.

Rackham never fails to stick to Barrie’s text and Peter is always shown as the infant he is, seven days old and not one day older: his white gown is a direct homage to the first book’s original title, The Little White Bird, and we’ll see Peter slowly losing his clothes following the adventures precisely as they are narrated in the book.

Birds live in Serpentine’s Island and Peter first reaches them in flight, while he still believes to be more bird than he really is. Upon knowing that he really is not, as we were seeing, he becomes stuck and the fairies take some getting used to him, too. As you can see, the concept of flight coming from fairies’ dust is completely absent in this younger Peter: if anything, they grant him flight just one time, as payment for his playing, and it’s done in the playful act of tickling his shoulders. Kensington Fairies, as we’ll see, are very different from Neverland Fairies, too.

Being that children are half-birds, Barrie proposes to us a version of the stork-carrying-babies myth (if you want to explore that theme, I suggest you start by reading here).

This idea of an enchanted island is of course nothing new and there’s a large tradition of islands being liminal spaces (meaning spaces where you can transit between the material world and a supernatural, parallel space of any kind): J.M. Barrie uses the idea not only in the much more famous Neverland island but also in a lesser-known work, Mary Rose, based on an old Scottish legend where children are stolen by fairies for a day and come back with no memory of what happened. There’s a couple of additional references in this article, and I really suggest you read Emma Hayes’ thesis ‘Betwixt-and-Between’: Liminality in Golden Age Children’s Literature (you can find it here).

As soon as Peter gets to the island, he gets accused by the fairies of not being a bird, therefore he submits his case to the wisest bird around, Solomon Caw. The bird’s name is of course a double trick: one part comes from King Solomon, to suggest its wisdom, while the other part is onomatopoeic for a crow’s call.

Barrie allegedly loved this illustration, where Rackham depicts Peter still in his “white bird” attire, sitting on a branch like a bird would, while the crow carefully informs of the facts of nature and breaks his ability to fly by introducing disbelief. On the lower portion of an illustration by the Serpentine surface and the horizon line with poplar trees, two mice are shining their shoes and they appear to be readying themselves to go to work. Once again, great care and attention are put to the details of their clothing, with striped socks and dotted scarfs.

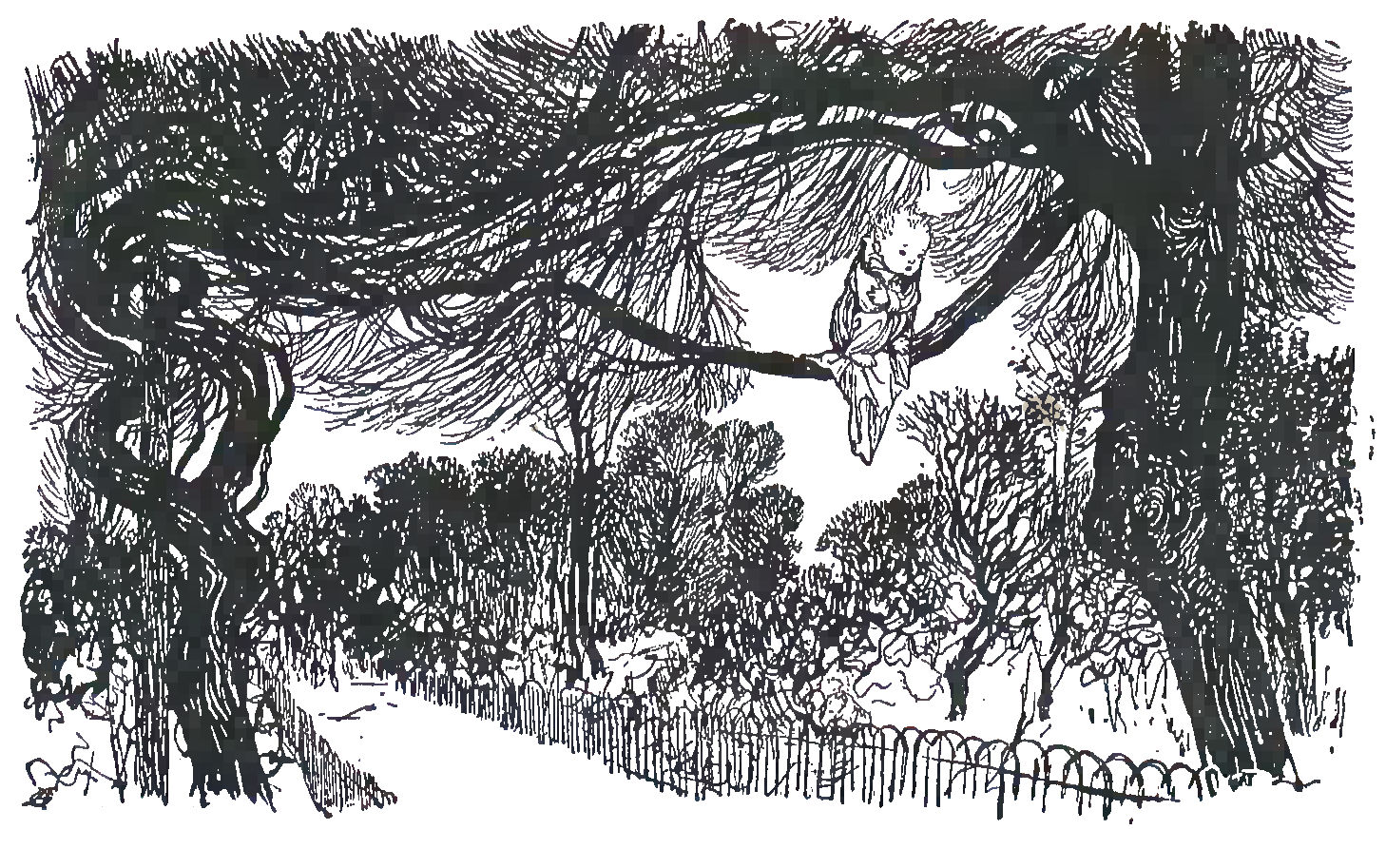

The same pose is held by Peter in a black and white illustration, and we can feel the incredible cold of a lonely child, in his nightgown, on the bare branches of a tree.

Solomon Caw is a recurrent character: we see him again in a rather hilarious episode where the poet Shelley tosses a five-pound banknote in the Serpentine River and the useless piece of paper floats to the Island’s shores. It’s a chance for Barrie to play with sarcasm around the value of money and to subvert the meaning of what’s considered to be important.

The concept is further reinforced by the fact that Serpentine Island is not a place where the concept of worth is unknown: they simply value and give meaning to different objects, as will happen for the thistle-kiss mix-up. This idea is conveyed by the information that Solomon is saving for retirement. He’s just saving what he considers to be valuable, like crumbs and bootlaces.

The only way Solomon could be saving for retirement would be if he had a job, which he does, and a very important one at that: he sends birds to their mothers after they are born on the Island and again there’s no distinction between babies and birds, at that stage, so basically Serpentine Island becomes the place where London babies are born. Again, this is a chance for Barrie’s to do some satire on London’s society: men and women born in the Sparrow’s Year are a little bit of a changeling, as Solomon had a shortage of thrushes (a species of passerine) and was forced to send sparrows even to ladies who requested thrushes. This apparently results in more vain human beings. It’s good to know there’s a scientific explanation.

Again, Rackham’s attention to clothing details is unparalleled.

Anyway, even if what we remember most is probably Peter’s association with faeries (in the next session), it’s worth pointing out that birds serve much more as helpers, in Kensington Gardens than the selfish and capricious fairies. It is a bird who tells Peter the truth about his nature and it’s again birds who bring him the beautiful discovery of a white Kite, a resemblance of that white bird Peter used to be. They show him the kite and repeat the demonstration several times for his delight, and they do never seem offended by the fact that, as any boy would, he forgets to thank them.

This is probably one of the most important passages when it comes to sadness and melancholy: aside from the great anguish of not being able to fly anymore, and therefore being stuck on the Serpentine Island where no human can go, Peter demonstrates a longing for a childhood he never had and his enthusiasm towards the kite turns pathetic when we learn that Peter even sleeps with the “wonderful white thing” because it had “belonged to a real boy”.

Eventually, Peter convinces the birds to help the kite take flight with him attached to it, and fly him over Kensington Gardens, but this turns out to be an unsuccessful attempt: the kite breaks and Peter is brought back down.

In particular, he falls into the Serpentine and is rescued by a pair of indignant swans, who brings him back to the Island. It should be no surprise to anyone that this first disastrous attempt prompts the birds not to offer any kind of further help in Peter’s flight attempts.

Oddly enough, it won’t be by flying but by returning to the bird’s realm through an entirely different element that he’ll be able to escape. Using a bare nest and constructing a sail with his own nightgown, he’s finally able to craft a boat and it’s again the wind carrying him towards the Gardens, but this time aided by the waters of the Serpentine. Between the bare nest, the cold wind, and the dark water, this is one of the illustrations conveying a harsher sense of freezing discomfort, which will only get worst when we step into winter.

The journey is not without troubles, as a storm arises and in Rackham’s illustration is even enough to scare the fishes, but his nightgown is able to attract fairies and finally convince them that he’s a boy and not a bird, and therefore they would have no bone to pick with him.

It’s worth mentioning that Peter will fly again, though it would probably be more proper to do so when talking about fairies: Queen Mab grants him a wish for his playing and Peter decides to use it for two small wishes instead. One of them is flying back home to the nursery he left. But we’ll talk about fairies next time.