The Wind in the Willows (4): Mr. Badger

Well, you didn’t think I would leave you hanging in the snow with Mole and Rat, did you? As usual, I wanted to do just one article and this got out of hand. I won’t definitely be doing all chapters, but – as I said – Mr. Badger is my favorite character. And right now […]

Well, you didn’t think I would leave you hanging in the snow with Mole and Rat, did you? As usual, I wanted to do just one article and this got out of hand. I won’t definitely be doing all chapters, but – as I said – Mr. Badger is my favorite character. And right now he’s waking up to the sound of Mole ringing the bell and Rat banging on the door, in a snowy winter night.

The Mr. Badger we are about to meet, as I have had the chance of saying in the previous chapter, is far from being the only Badger in children’s literature.

In Beatrix Potter‘s The Tale of Mr. Tod (1912), the fox of the title is the arch-enemy of Tommy Brock, the badger, far from being a positive character. Brock abuses the hospitlity of Mr. Bouncer, the father of Benjamin Bunny, and at the first chance he kidnaps the children of Benjamin Bunny and his wife Flopsy, and hides them in the oven of Mr. Tod’s house. Upon the return of the fox, and while the two fight, Peter and his parents rescue the other rabbits. The story was probably influenced by the tales of Br’er Rabbit, though his opposers are usually Br’er Fox and Br’er Bear and Potter’s usage of a badger is to be considered unique in his genre.

“Tod” is surely a very common name for a fox? It is probably Saxon, it was the word in ordinary use in Scotland a few years ago, probably is still amongst the country people. In the same way “brock” or “gray” is the country name for a badger. I should call them “brocks” – both names are used in Westmoreland. “Brockholes”, “Graythwaite” are examples of place names; also Broxbourne and Brockhampton […] “Hey quoth the Tod/it’s a braw bright night!/The wind’s in the west/and the moon shines bright”—Mean to say you never heard that?”

A better badger features in Fantastic Mr. Fox (1970) by Roald Dahl, where he aids Mr. Fox in an effort to exact vengeance upon a family of dim-witted farmers. Here we have a more heroic and frindly badger, participating in a reclaiming that epically resounds of the same flavours we will taste in the reclaiming of Toad Hall. The story was was published in 1970, by George Allen & Unwin, the same published of The Hobbit, and featured illustrations by Donald Chaffin. The Puffin paperback, in 1974, had illustrations by Jill Bennett and later editions had pictures by Tony Ross (1988) and Quentin Blake (1996). The book is also a 2009 stop-motion movie directed by Wes Anderson, with George Clooney voicing Mr. Fox, Meryl Streep voicing Mrs. Fox, and Bill Murray as Badger.

Donald Chaffin’s illustration of Badger and Mr. Fox.

But let us go back to our Mr. Badger in The Wind in the Willows, a character who arrives angrily at a well-locked door, meaning business. This has to be the first door with a padlock we ever meet in the tale, and for a very good reason. Let us not forget that Badger lives in the same Wild Woods that have terrifies Mole and that, according to Rat, you cannot enter if not in pairs.

“Now, the very next time this happens,” said s gruff and suspicious voice, “I shall be exceedingly angry. Who is it this time, disturbing peoole on such a night? Speak up!”

He is ready to change his tone and attitude when he realizes that it’s a friend who’s been banging at the door. According to Peter Green, who writes Grahame’s biography, Badger is highly autobiographical, as our author didn’t like social calls at all, but is also influenced by two characters in Richard Jeffries‘ last published novel, Amaryllis at the Fair (the father and the grandfather). It’s an author we have already met while talking about the possible inspirations for the Wild Wood itself.

[Amaryllis] marveled how he could be so rough sometimes… he who was so full of wisdom in his other moods, and spoke, and thought and indeed acted as a perfect gentleman.

Badger opens the door in another one of E.H. Shepard’s illustrations.

Badgers do not hibernate in winter and Grahame seemed to have taken that into consideration because, while Rat’s behaviour in the first part of the story has been described as the one of an animal dozing off, Badger is described as being «on his way to bed», wearing a long dressing-gown and old slippers like the Ebeneezer Scrooge we often see being visited by the ghosts. He looks down at the two lost wanderers, both in a paternalistic and in a physical sense (it’s a badger, it’s bigger than a mole or a rat, and at least among each other the animals seem to keep proportions) and invites them in, promising fire and supper.

The entrance of Badger’s house is described as «long, gloomy, and, to tell the truth, decidedly shabby passage» (shabby is a word Grahame has already used for Badger’s door-mat) and it leads to a sort of entrance hall, equally gloomy, «out of which they could dimly see other long tunnel-like passages branching, passages mysterious and without apparent end».

Badger’s house is more like an underground city, a splendid underground city of old, at the very heart of the Wild Woods, and we’ll be lucky enough to get a glimpse of its splendor and its history, but for now we follow Badger to more familiar places, through a «stout oaken comfortably-looking door». Our friends have had enough of mysteries and adventures, for one night, and so have we.

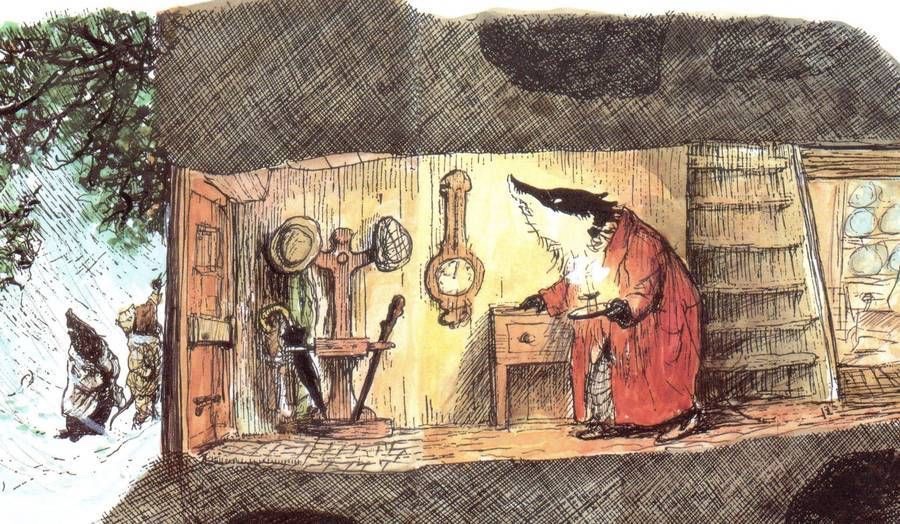

Illustration by Philip Mendoza

Badger’s hearth is the next thing we find, when one of those doors is flung open by our gracious host, and the kitchen is described in detail, with a well-worn red brick floor and a wide hearth, with two big logs burning between two chimney-corners tucked in the wall, under a smoky ceiling. There are two high-back oaky benches facing the fires, shiny with long wear and called settles as it is customary for a kind of furniture you would usually find in a pub, and they are equally described as you would do in a public place, as «further sitting accommodations for the sociably disposed».

Illustration by Inga Moore

In the middle of the room, instead of the hearth of a longhouse, sits a long rectangular table with other benches and an armchair at one end, where our guests can still see the remains of Badger’s supper. There’s no doubt that we have enered the residence of a lord of the land, a gentleman who sits in his armchair even while having dinner by himself.

Badger’s house is well-furnished with food for the winter: hams, dried herbs, nests of onions, and baskets of eggs in the main hall; piles of apples, turnips and potatoes, baskets full of nuts, and jars of honey in the guest quarters.

It seemed a place where heroes could fitly feast after victory, where weary harvester could line up in scores along the table and keep their Harvest Home with mirth and song, or where two or three friends of simple tastes could sit about as they pleased and eat and smoke and talk in comfort and contentment.

The inspiration couldn’t be clearer and sets the tone for Badger’s character. As Humphrey Carpenter suggests, when he’s not obsessing over the author’s sexuality:

Its appeal is multiple. It hints at the mead-halls of such poems as Beowulf; Grahame says that ‘heroes could fitly feast’ in it, a phrase whose alliteration faintly recalls Anglo-Saxon verse. To Grahame’s generation it must also have had William Morris-like hints of an earlier, pre-industrial, and therefore ideal society where distinctions of class seemed unimportant when food was being dealt out, and men of all ranks sat together in the lord’s hall or by the yeoman farmer’s hearthside.

Badger fetches clean and dry clothes for his guests (dressing gowns and slippers) and he himself heals and bathes Mole with warm water, as a host would have done in Ancient Greece, a detail is too often overlooked in illustrations and narrations. Without any care for fake manners, they rest and dine and indulge in conversation. They chatter about stuff we would see in the next chapters: how Toad is of course proving to be an awful driver, and been hospitalized three times, and drowning in fines. When all is said and all is done, Badger show the guests to their quarters (not even rooms: that’s the grandeur of his underground mansion) and this is probably the first time we explicitly see that Mole and Rat are sleeping together in lavender-scended linen sheet. Nancy Barnhart takes upon herself that the bed are two, but they are arranged like a cool parent would arrange them for you and your boyfriend.

Their accomodation seems to be a quote from John Keats‘s poem The Eve of St. Agnes, in 1819:

And still she slept an azure-lidded sleep,

In blanched linen, smooth, and lavender’d,

While he from forth the closet brought a heap

Of candied apple, quince, and plum, and gourd;

With jellies soother than the creamy curd,

And lucent syrops, tinct with cinnamon;

Manna and dates, in argosy transferr’d

From Fez; and spiced dainties, every one,

From silken Samarcand to cedar’d Lebanon.

They take their time to rise for breakfast, at their host’s instructions, and they have a very traditional bacon and eggs breakfast in the main hall.

An illustration by contemporary illustrator Chris Dunn.

In the scene, we also casually meet two hedgehogs, one named Billy, that are having a porridge in Badger’s hall. The two spring up at the sight of the houselord’s guests, and Rat graciously tells them to stay seated. It is immediately clear that it is Badger’s custom to graciously give shelter to lost animals that he considers his friends, though not his peers. It will become even clearer when Badger will reassure Mole that he will spread the word around and nobody will dare lay a finger on him in the Wild Woods, as any friend of his walks where he pleases. Yes, Godfather.

Illustration by Inga Moore

The hedgehogs dropped their spoons, rose to their feet, and ducked their heads respectfully.

«And at last we happened up against Mr. Badger’s back door, and made so bold as to knock, sir, for Mr. Badger he’s a kind-hearted gentleman, as everyone knows», they add, though it’s unclear whether their reverence is sincere or somehow induced. Badger is starting to look as something inbetween a gracious lord and a noble mobster, though there’s probably no difference, now that I think about it. Right in the middle of breakfast, Otter joins in, having been worried about the absence of Rat and Mole. The riverbank is the kind of community where neighbors will come looking for you if you don’t turn in for the night, whether you like it or not.

Bransom’s otter, tracking Rat and Mole in the snow.

Badger also emerges from his study and sends off the two young hedgehogs, with sixpence each and a pat on the head. Badger too has invisible servants, as he says that he’ll send someone with them to show them the way.

It is during luncheon, as Otter and Rat are river-gossiping, that Badger and Mole really connect. Mole takes the chance of saying how he appreciated Badger’s house, being an underground-dweller himself, and his arguments strike a chord with our gracious lord.

“Once well underground,” he said, “you know exactly where you are. Nothing can happen to you, and nothing can get at you. You’re entirely your own master, and you don’t have to consult anybody or mind what they say. Things go on all the same overhead, and you let ’em, and don’t bother about ’em. When you want to, up you go, and there the things are, waiting for you.”

After lunch and after much talk of the insecurities that lurk above ground, from fires to floods, Badger and Mole leave Rat and Otter by the fireplace, having an argument about eels, and Badger leads Mole (and us) further underground. This is where it becomes explicit that Badger’s house is in fact an underground city, a city of people, probably modelled after the old Saxon ruins Grahame was quit fascinated about.

Arthur Rackham’s illustration of Badger showing Mole the ancient dwellings of his halls.

“Well, very long ago, on the spot where the Wild Wood waves now, before ever it had planted itself and grown up to what it now is, there was a city—a city of people, you know. Here, where we are standing, they lived, and walked, and talked, and slept, and carried on their business. Here they stabled their horses and feasted, from here they rode out to fight or drove out to trade. They were a powerful people, and rich, and great builders. They built to last, for they thought their city would last for ever.”

According to Green, Grahame’s biographer, it’s possible that these underground dwellings were also based on the undergrounds built by William John Cavendish Bentinck-Scott, fifth Duke of Portland, under his residence of Welbeck Abbey, in Nottinghamshire. He was nicknamed “the Gentle Mole” and his underground tunnels had libraries, a billiard room, and a huge roller-skating ring, all supported by arched ceilings and dimly lighted through glass bull’s-eye windows, stables and a riding school with a glass roof. The story was well-known to Grahame because of one G.H. Druce claim to the estate, known in papers as the Druce Case.

Abandoned underground kingdoms make us of course think of the dwarven kingdom of the Lonely Mountain in The Hobbit and, most impirtantly, of the Mines of Moria in The Lord of the Rings, the splendid underground halls, chambers, network of tunnels and mines under the Misty Moutains, where Balin finds his undoing.

Tolkien’s inspiration for this, aside from the name which is casually taken from our next Sunday’s Norse Tale, was probably Tolkien’s visit and study of an old mysteric temple that was excavated in Gloucestershire around 1928. The place was called Lydney Park, and Tolkien was invited to study an inscription going along the lines of:

For the god Nodens. Silvianus has lost a ring and has donated one-half [its worth] to Nodens. Among those who are called Senicianus do not allow health until he brings it to the temple of Nodens.

The place was called Dwarf Hill and this encounter was one of the most inspirational for the whole development of Tolkien’s Middle-Earth, at least according to Tom Shippey.

Anyway, it is through one of these passageways, leading to the edges of the Wild Woods, that our two heroes Rat and Mole, led by the gentleman adventurer Otter, return to their familiar and trusted friend the river. As we’ll see, however, al, this underground dwellings has made our Mole a little homesick. That would be Chapter V, but you’re going to have to wait for that.

E.H. Shepard’s illustration of Otter leading Rat and Mole oit of the Woods.

One Comment