East of the Sun, West of the Moon

Yesterday I found myself writing quite an extensive piece about Kay Nielsen, che extraordinary Danish illustrator who prompted me to buy at last this long-wanted book. It is worth mentioning that, as a fan and amateur scholar of J.R.R. Tolkien in my younger years, the beauty of Nielsen’s work is not the only reason I […]

Yesterday I found myself writing quite an extensive piece about Kay Nielsen, che extraordinary Danish illustrator who prompted me to buy at last this long-wanted book. It is worth mentioning that, as a fan and amateur scholar of J.R.R. Tolkien in my younger years, the beauty of Nielsen’s work is not the only reason I wanted this book. Yeah, you heard me right: I used to hang around with a group of people who illustrated, sang, dressed up and/or studied Tolkien. Some of the work I did is still on-line at the page of the group I used to hang around with. Some of my closest friends of today came from that group, and though the blog hasn’t been active in four years it has been on-line for ten years before that. The most serious stuff is collected here, although my most prominent work was in catalogues of art exhibitions and is stuck in an old hard-drive. I might as well dig it up and throw it on-line: I vaguely remember working my ass off on stuff from The Annotated Hobbit. Anyway. It is highly rare that, as a fan of Tolkien, you manage to grab something that was inspirational to him. Particularly because there’s very little. One of the reasons he started to write was, at least accordingly to scholar Tom Shippey, because there was so little: there wasn’t enough mythology that could be claimed as English, so he went ahead and write it. A man after my own heart. The little stuff you have, includes Kalevala and Beowulf, works by George MacDonald (The Princess and the Goblin being the only work he ever admitted being influenced by, but there’s also The Golden Key and At The Back of the North Wind… we wrote something about it here) and, among this very little stuff, East of the Sun West of the Moon.

1. East of the Sun and West of the Moon: Old Tales from the North

Old Tales from the North is a collection of Norse legends, put together by Peter Christen Asbjørnsen and Jørgen Moe back in 1840. The two were friends and passionate about folk tales and had spent years travelling on foot to ancient communities in Norway, collecting their stories about trolls, witches, and giants. The community they visited were very diverse in nature: from farmlands to fishing communities to mining communities. The origin of the stories they collected was just as mixed: they contained traces of ancient Norse mythology just as much as Viking traces just as much as what medieval Christian missionaries tried to do to those stories in order to cleanse them of their pagan background.

Once they had published their collection, between 1841 and 1943 under the title Norske Folkeeventyr, the public was unsympathetic towards their work, but they struck a chord with scholars all over Europe, even receiving appreciation from the Brothers Grimm themselves, who had been collecting folk tales in the very same way and whose collection from 1812 had inspired the two friends to undergo the very same operation in Norway. The Grimms defined Moe and Asbjørnsen work as a collection of «the best folktales that exist» and I can’t help but imagining the two fangirling at receiving the news. The two kept working and the final collection contains 60 tales. It was published around 1852 and still is one of the foundations of folk lore in Norway: it tremendously influenced the National identity and still is one of the most beloved collections of stories in Northern Europe. It’s fair to say that it played a big part in shaping Norway’s identity, especially considering that its independence from Denmark, and its first constitution, is to be traced precisely in those years (the first draft of the constitution, if I’m not mistaken, is from 1814). Asbjørnsen went on with his work and he published a solo work in 1845, another collection of Norwegian fairy-tales titled Huldre-Eventyr og Folkesagn.

The stories were first translated into English in 1859 by Sir George Webb Dasent. Several illustrated editions had been published since 1879 (more on that later) but London publisher Hodder & Stoughton approached the authors with something different in mind: they collected thirteen tales among the ones already translated by Sir Dasent, added an original tale by the two folklorists in a translation by H.L. Brackstad and the Danish tale Prince Lindworm. They named the collection after the leading tale, East of the Sun and West of the Moon, and commissioned illustrations to Kay Nielsen. This is the book I have.

2. What are these stories about?

There’s a set of recurring themes, in Folklore. The idea is that, no matter how far apart from each other, the ideas we work around as human beings can be traced back to the same set of themes. The general idea of this is to be traced back in 1864 to an Austrian, one Johann Georg von Hahn, who identified 44 formulas to categorize his collection of Greek and Albanian folk tales. The idea quickly spread and it was furtherly implemented in 1866 by one Sabine Baring-Gould, who expanded the set to 52 styles and called them story radicals. They were then furtherly expanded to 70 by folklorist Joseph Jacobs, in his Appendix C to the Handbook of Folk-Lore.

The index still in use today, however, was developed by Finnish folklorist Antti Aarne in 1910, then revised and translated into English by American folklorist Stith Thompson. It is commonly known as the Aarne–Thompson system, although his complete name would be ATU Index, thus including the further expansion made by German folklorist Hans-Jörg Uther in 2004.

The concept of Story Type was such defined by Thompson:

A type is a traditional tale that has an independent existence. It may be told as a complete narrative and does not depend for its meaning on any other tale. It may indeed happen to be told with another tale, but the fact that it may be told alone attests its independence. It may consist of only one motif or of many.

In reading stories such as East of the Sun, West of the Moon, we find some recurring themes and we’ll be tempted to pair them with other myths from different areas of th globe. This is most appropriately done through the ATU Index. I will also be using what Christopher Booker calls The Seven Basic Plots.

3. The stories

The stories within the collection are:

- East of the Sun and West of the Moon;

- The Blue Belt;

- Prince Lindworm (the outsider story);

- The Lassie and her Godmother;

- The Husband who was to mind the House;

- The Lad who went to the North Wind;

- The Three Princesses of Whiteland;

- Soria Moria Castle;

- The Giant who had no Heart in His Body;

- The Princess on the Glass Hill;

- The Widow’s Son;

- The Three Billy Goats Gruff;

- The Three Princesses in the Blue Mountain;

- The Cat on the Dovrefell;

- One’s Own Children are always prettiest.

I can’t promise I will be able to cover all of them. I probably won’t. Hell, I don’t even know if I’ll be able to cover more than one. But I’ll certainly do my best. I will be your wintertime storyteller.

3.1. East of the Sun and West of the Moon

The main them of this story is within the “Supernatural or enchanted relatives” group, in the ATU index (400-459) and particularly it’s 425A, labeled “The search for the lost husband”. Think Eros and Psyche or Beauty and the Beast, or the German version The Singing, Springing Lark. If you want to read more about the theme, I suggest you take a look here.

You can read different versions of the story here, but the plot goes pretty much like this: there’s a village with a poor man and the poor man is approached by a Great White Bear. The Bear promises to make him rich if he agreed to give him his youngest and fairest daughter in marriage and the man agrees. After some reluctance, the girl agrees too. She and the beast take off, in one of the most iconic moments of the fairy-tale: the one where she is seen riding the back of the big bear.

Next Thursday evening came the White Bear to fetch her, and she got upon his back with her bundle, and off they went.

They arrive at a big and rich castle, where the bear lives, and she doesn’t get to see him. She is given everything she desires, but the castle is deserted and her needs are attended by invisible servants. Sounds familiar?

Then the White Bear gave her a silver bell; and when she wanted anything, she was only to ring it, and she would get it at once.

Precisely as it happens in Eros and Psyche, the bear is no bear but a cursed prince and he visits her by night in his human form. There are no candles nor lanterns in the house, so the girl never sets eyes on her husband in his true form, although you’re bound to realize you are not having sex with a bear. At least, I think. Anyway, everything is fine but the girl gets homesick and requires to go back to her house, to visit her family. The prince, who has fallen in love by now, agrees.

“Well, well!” said the Bear, “perhaps there’s a cure for all this; but you must promise me one thing, not to talk alone with your mother, but only when the rest are by to hear; for she’ll take you by the hand and try to lead you into a room alone to talk; but you must mind and not do that, else you’ll bring bad luck on both of us.”

As you might imagine, this doesn’t go well, though the bear knew never to trust a mother in law. Again, precisely like in Eros and Psyche, her mother brings doubt and mistrust into the couple. In this situation, she gives the girl some good advice.

“My!” said her mother; “it may well be a Troll you slept with! But now I’ll teach you a lesson how to set eyes on him. I’ll give you a bit of candle, which you can carry home in your bosom; just light that while he is asleep, but take care not to drop the tallow on him.”

The candle is smuggled in the house and the girl uses it at nightfall after her lover has fallen asleep. He indeed is a beautiful prince, but she is too charmed to pay attention: she spills wax on him, he wakes up and the enchantment is broken. He vanishes, alongside the castle, because in setting eyes upon him she failed in freeing him of his curse.

“What have you done?” he cried; “now you have made us both unlucky, for had you held out only this one year, I had been freed. For I have a stepmother who has bewitched me, so that I am a White Bear by day, and a Man by night. But now all ties are snapt between us; now I must set off from you to her. She lives in a castle which stands East o’ the Sun and West o’ the Moon, and there, too, is a Princess, with a nose three ells long, and she’s the wife I must have now.”

Well, shit.

Thus, the search for the lost husband begins. The girl starts a long and perilous journey in which she meets three neighbors: an old woman playing with a golden apple, who gives her a horse and the apple, another woman with a golden carding comb, who gives her another horse and the comb, and a third woman with a golden spinning wheel, who gives her another horse and the spinning wheel. This last woman tells her that the East Wind might know something and she sets her on her way.

The girl then interrogates the East Wind, who sends her to the West Wind, who sends her to the South Wind, who sends her to the North Wind. At last, the North Wind knows where the palace has vanished. The North Wind always knows stuff.

Once the girl finds the castle, with the Troll’s daughter and the prince’s stepmother, she uses the golden treasures as bargaining chips in order to gain him back and… you’ll have to read ghe story to see how it ends.

3.1.1. Illustrations to the tale

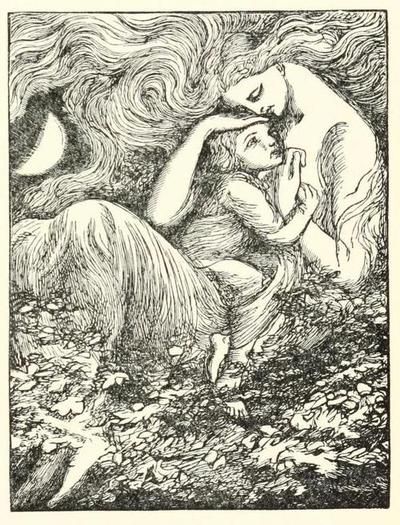

Kay Nielsen provided 5 colored illustrations to the tale: the iconic girl on bearback, the moment of desperation when the two lovers have to say goodbye, and another beautiful moment when the girl is left alone, in despair, and the “search for the lost husband” begins.

And then she lay on the little green patch, in the midst of the gloomy thick wood.

The fourth one is a stunningly heroic picture of the North Wind over the sea, where you can clearly see those Japanese influences I was talking about in my last piece. Sometimes this picture is wrongly referred to as an illustration of the prince. Guys, there’s nothing heroic about the prince in this tale: he just goes around sleeping with people.

The last picture is a beautiful happy ending: the two lovers above the sky, east of the Sun, west of the Moon.

Nielsen also did two black and white illustrations, for this tale: the bear knocking on the door to access the palace, the girl wandering in search.

But Nielsen hasn’t been the only one to illustrate the novel over the years.

The 1910 edition, for instance, was illustrated by the brothers Reginald and Horace J. Knowles, who did exquisite work also on children stories such as The Land of Goodness Knows (read about it here), The Enid Blyton Book Of Fairies, The Land of Far Beyond (also by Enid Blyton) and Mrs Nimble And Mr Bumble (by Alison Uttley, 1944). They also worked on illustrating fairy-tales and legends, their most important work probably being The Legend of Glastonbury (1948).

When the tale appeared in Andrew Lang’s Blue Fairy Book, our connection with Tolkien as we’ll see, it was illustrated by British artist Henry Justice Ford.

In 1992, another edition was illustrated by Irish artist P.J. Lynch, who also did A Bag of Moonshine by Alan Garner (1986), a collection of folk tales from England and Wales, The Christmas Miracle of Jonathan Toomey by Susan Wojciechowski, and When Jessie Came Across the Sea by Amy Hest (1997). For all three works, he won the Mother Goose Award. His work on the Norse fairy-tale is just incredible.

One of my favorite illustrators of all times, however, is also responsible for the re-telling of the story: I’m talking about Michael Hague who approached the legend in 1980 with his wife Kathleen. Hague is also the author of one of my favorite sets of illustrations for The Hobbit, a book he worked on in 1984 as his birthday gift to me. I love everything about his style, particularly the use of colors and shadows. He also did Peter Pan and The Wind in the Willows, another book I simply adore.

American illustrator Mercer Mayer also came across retelling and illustrating the story, and I have no idea where he found the time because this guy draws like there’s no tomorrow (take a look at his bibliography here).

There’s also a beautiful edition retold and illustrated by British artist Jackie Morris.

If you’re looking for something different, I suggest you take a look at Vivienne Flesher‘s work, who illustrated the story with beautiful watercolors.

Tale influences: Tolkien, Lewis, and Pullman

The story is one of the most famous of the collection and, with its powerful set of themes and images, had a tremendous influence on literature. In their Companion and Guide, Hammond and Scull trace back an acknowledgment to the importance of these tales by J.R.R. Tolkien through his lecture On Fairy Stories.

It is clear… that Tolkien was familiar with fairy-stories from many sources… but generally preferred more traditional tales, such as those collected by the Brothers Grimm in Germany, by Asbjørnsen and Moe in Scandinavia, by Campbell in Scotland.

Andrew Lang is mentioned multiple times throughout his notes and writings and we know for a fact his important influence on Tolkien while he was shaping his world. He was also critical towards the approach taken by Sir Webb Dasent in his translation and doesn’t miss the chance of teasing him directly in his abovementioned essay.

In Dasent’s words I would say: ‘We must be satisfied with the soup that is set before us, and not desire to see the bones of the ox out of which it has been boiled.’ Though, oddly enough, Dasent by ‘the soup’ meant a mishmash of bogus pre-history founded on the early surmises of Comparative Philology; and by ‘desire to see the bones’ he meant a demand to see the workings and the proofs that led to these theories. By ‘the soup’ I mean the story as it is served up by its author or teller, and by ‘the bones’ its sources or material–even when (by rare luck) those can with certainty be discovered. But I do not, of course, forbid criticism of the soup as soup.

Tolkien scholar Verlyn Flieger dedicates to this “soup of bones” concept the fourth section of her There Would Always Be a Fairy Tale. More Essays on Tolkien.

I am no scholar, of course, and my dissertation is purely for a friend’s amusement, but there are a couple of themes you can use to connect East of the Sun and West of the Moon to what Tolkien wrote across the years. Oddly enough, the bear isn’t one of them. Although we do have a bear (the shapeshifter in The Hobbit) and there are Norse roots to the host of Carrock, these roots (at least accordingly to another great Tolkien scholar, T.A. Shippey, are to be traced back to the Hrólfr Kraki saga and, of course, Beowulf.

Another reference might be seen in one of Bilbo’s songs.

Still round the corner there may wait

A new road or a secret gate

And though I oft have passed them by

A day will come at last when I

Shall take the hidden paths that run

West of the Moon, East of the Sun.

Though it is fairly likely that the reference was a direct homage to a tale Tolkien had every right to like, there’s also to be said that the “East of the Sun, West of the Moon” sentence is a way of referring to a very far away place. Tolkien’s poem of 1915, The Shores of Faery, also begins with “West of the Moon, East of the Sun”.

Still, the way the Sun and Moon are used in Tolkien’s mythology, especially when it comes to elves going to die on a boat, has resonant Norse roots.

There’s also something else that always fascinated me and it’s the personified use of winds when it comes to carrying people in their search, helping people in their struggles, and bringing tales.

“Farewell,” they cried, “Wherever you fare till your eyries receive you at the journey’s end!” That is the polite thing to say among eagles.

“May the wind under your wings bear you where the sun sails and the moon walks,” answered Gandalf, who knew the correct reply.”

The exchange above comes from the farewell Gandalf bids to the Eagles the first time they rescued them, after the warg attack. The portion where winds are treated as main characters, though, is the Lament for Boromir, where different people interrogate different winds, personified, in search of the fallen hero’s whereabouts.

Through Rohan over fen and field where the long grass grows

The West Wind comes walking, and about the walls it goes.

‘What news from the West, O wandering wind, do you bring to me tonight?

Have you seen Boromir the Tall by moon or by starlight?

‘I saw him ride over seven streams, over waters wide and grey,

I saw him walk in empty lands until he passed away

Into the shadows of the North, I saw him then no more.

The North Wind may have heard the horn of the son of Denethor,

‘O Boromir! From the high walls westward I looked afar,

But you came not from the empty lands where no men are.’

From the mouths of the Sea the South Wind flies, from the sandhills and the stones,

The wailing of the gulls it bears, and at the gate it moans.

‘What news from the South, O sighing wind, do you bring to me at eve?

Where now is Boromir the Fair? He tarries and I grieve.

‘Ask not of me where he doth dwell – so many bones there lie,

On the white shores and the dark shores under the stormy sky,

So many have passed down Anduin to find the flowing Sea.

Ask of the North Wind news of them the North Wind sends to me!’

‘O Boromir! Beyond the gate the seaward roads runs south,

But you came not with the wailing gulls from the grey sea’s mouth’.

From the Gate of the Kings the North Wind rides, and past the roaring falls,

And clear and cold about the tower its loud horn calls.

‘What news from the North, O mighty wind, do you bring to me today?

What news of Boromir the bold? For he is long away.’

‘Beneath Amon Hen I heard his cry. There many foes he fought,

His cloven shield, his broken sword, they to the water brought.

His head so proud, his face so fair, his limbs they laid to rest,

And Rauros, golden Rauros-falls, bore him upon its breast.

‘O Boromir! The Tower of Guard shall ever northward gaze,

To Rauros, golden Rauros-falls, until the end of days.

Didn’t I tell you? The North Wind always knows.

In 1950, C.S. Lewis approached the Eros and Psyche myth in his Till We Have Faces novel, but I’m more interested in the influences East of the Sun and West of the Moon might have had on his most important series of works: The Chronicles of Narnia. Whereas the influence of tales such as Danish fairy-tale The Snow Queen is fairly recognizable, the Norse roots are a little more blurred.

Another guy who apparently owns a lot to this fairy-tale is Philip Pullmann, with His Dark Materials: if you have a picture of a little girl riding a polar bear, there’s a chance it comes from this, and there’s also echoes of a bear prince, although there are other stories that might be more significant in this regard.

6 Comments