The Wind in The Willows (7): The Piper at the Gates of Dawn

After Dulce Domum, the charming Christmas chapter in which Mole brings Rat back to his old house and Rat proves to be like the best companion ever, Chapter 6 in The Wind in the Willows is “Mr. Toad”, and revolves around the misadventures of Toad whom we met in Chapter 2. It’s the very beginning […]

After Dulce Domum, the charming Christmas chapter in which Mole brings Rat back to his old house and Rat proves to be like the best companion ever, Chapter 6 in The Wind in the Willows is “Mr. Toad”, and revolves around the misadventures of Toad whom we met in Chapter 2. It’s the very beginning of the grand saga of Toad driving his car around, causing accidents, being arrested, breaking free of jail and coming back to his house only to find out he has to conquer it back. The story is included in pretty much every collection that revolves around the character of Toad and, as I said, I am not a fan of the abovementioned amphibian. And I don’t care that his tale is supposedly modelled around the misfortune of Oscar Wilde.

If you really like Toad, I’ll give you one of the character sheets drawn for the Walt Disney adaptation, by James Bodrero. Bodrero was one of the artists to work on the early concept of the project and I do believe I talked about him here. That’s all the Toad we’re going to have.

I set off in trying to prove to you that there’s a great deal more to The Wind in the Willows than the adventures of Toad and this chapter is another charming Toad-free short story in the grand pastoral picture of the book. The chapter is titled “The Piper at the Gates of Dawn”, which also is Pink Floyd’s first album, so good luck finding any specific illustration. It is perhaps the most Pastoral chapter of them all, by definition, since it’s the chapter in which we meet Pan, a meeting Tolkien fiercely objected upon (and surely not because he was Catholic, as some critics would try to convince you, but because he felt it was out of place and out of tone, just as much as Christmas in the Chronicles of Narnia).

I personally think that in Pan we have that addition of an extra colour that spoils the palate: but it only comes in one corner of the delightful picture. Pan has no business here: at least not explicit and revealed.

Despite of what Tolkien thought, I like this chapter and I think it’s a suitable ending to my Wind in the Willows selection.

The Story and its Sources

The story starts, as we would do in a movie, with a close-up on a bird singing.

The bird is called a Willow-Wren, which is now known as a Willow warbler, and it’s a small passerine who mostly feeds on insects, a heavily migratory leaf warbler which breeds around Ireland and Great Britain, and then spends the winder in sub-Saharan Africa. The name “warbler” was standardized by William Yarrell in 1843, but here Kenneth Grahame uses the old-fashioned name, probably for the same reason he mentioned the telegraph in Dulce Domum, or because the name “warbler” didn’t really stick.

It is summer again: the sky is still bright, despite being 10 pm, and the torrid afternoon is just about rolling away at the cold finger of the night we are revealed to be midsummer’s night. Mole has come home from an afternoon with friends and he found that Rat hasn’t come back yet from his long-standing engagement with Otter, so here he is, standing on the riverbank, waiting for Rat to return, as an anxious and possibly a tad jealous wife. The term “comrade” here, referred to Mole and Otter, only adds to this lingering gentlemanly gay feeling we’ve been having throughout all the book, as Walt Whitman himself uses the term as a synonym of that kind of relationship between men and men. To be fair and honest, in 1890 John Addington Symonds wrote to Whitman: “In your conception of Comradeship, do you contemplate the possible intrusion of those semi-sexual emotions and actions which no doubt do occur between men?”. He denied, answering: “…that the calamus part has even allow’d the possibility of such construction as mention’d is terrible—I am fain to hope the pages themselves are not to be even mention’d for such gratuitous and quite at this time entirely undream’d & unreck’d possibility of morbid inferences—wh’ are disavow’d by me and seem damnable”. And so would Kenneth Grahame. Especially while overlooking the prison in which Oscar Wilde had been taken. Let us just take a look at Whitman’s verses and bask in the perfection of Rat and Mole’s relationship, whatever that might be.

For who but I should understand lovers, and all their

sorrow and joy?

And who but I should be the poet of comrades?

At last Rat is back and, as usual, we live that experience through Mole’s sharp senses. In this situation, as affectionate lovers would, we recognise his «light footfall» and rejoice in his return.

“You stayed to supper, of course?” said the Mole presently.

“Simply had to,” said the Rat.

Alas, his friend Otter was in no cheerful mood, as one of his sons – little Portly – had gone missing again. Portly is described as an adventurous little child, who’s always straying off and getting lost, and turning up again, and Mole isn’t too preoccupied with the matter, but Rat insists that this time it seems to be different: the wee lad has been missing for some days and the Otters have hunted high and low for him, and no other animal seems to have found him.

Otter is afraid his son has gone swimming near the weir, one of the many features of a canal that gets mentioned in the book: it’s a barrier altering the flow and it usually results in small waterfalls which tumultuously cascade down to a lower level, and if little Portly can’t swim very well, we’re right to fear the worst. And then, as Rat adds, there are also other things to be worried about.

And then there are—well, traps and things—you know.

Unfortunately, though Grahame never goes as far as making it explicit, the hunting of river otters was a widely popular sport, especially around the Thames. We get a clear and unsettling description from a book Grahame knew well, Richard Jeffries‘ Nature Near London:

Every effort is made to exterminate the otter. No sooner does one venture down the river than traps, gins, nets, dogs, prongs, brickbats, every species of missile, al the artillery of vulgar destruction, are brought against its devoted head.

Londoners, I think, scarcely recognise the fact that the otter is one of the last links between the wild past of ancient England and the present days of high civilization.

Otter is nervous, and this is reason enough for Rat. More than nervous, Otter is spending his nights holding watch in the specific place he taught his son to swim and catch fishes, in the vain hope the lost child will come wandering near that very well-known place and will stop in its familiar premises, perhaps to play. In this case, Grahame describes in detail the place, with just a few words, and also gives us a hint of how the Wide World is pushing through the gates of our very own river paradise: the place in question is called a Ford, a shallow crossing specifically picked by Otter to teach his son because of the low level of the water: now they have built a bridge over the ford and this probably has altered both currents and scenery, possibly enough for little Porty not to recognise the familiar place. Hence, Otter keeps watch. The picture is just heart-breaking.

Having told the tale, Rat proposes to turn in for the night, «but he never offered to move» (just another way of Grahame to tell us what’s really in Rat’s mind and how he’s waiting for his companion to make the first move). The gentle and sensitive Mole doesn’t disappoint. He is simply too upset and reads the companion’s mind: it’s not a night to sleep, it’s midsummer and the light will be on soon, and it also happens to be a full moon. He proposes to get the boat out and paddle upstream, in search of the child, and even if he doesn’t turn out they might be able to hear some rumours from the other animals, «some news from the early-risers». And so they do: they take out the boat and Rat carries it through the dark nightly waters: it’s probably the first time we see Rat paddling since he has taught it to Mole, and this gives us an idea of the danger of the situation.

Out in midstream, there was a clear, narrow track that faintly reflected the sky; but wherever shadows fell on the water from bank, bush, or tree, they were as solid to all appearance as the banks themselves, and the Mole had to steer with judgment accordingly. Dark and deserted as it was, the night was full of small noises, song and chatter and rustling, telling of the busy little population who were up and about, plying their trades and vocations through the night till sunshine should fall on them at last and send them off to their well-earned repose. The water’s own noises, too, were more apparent than by day, its gurglings and “cloops” more unexpected and near at hand; and constantly they started at what seemed a sudden clear call from an actual articulate voice.

The description of this night-time river is simply incredible and I leave you with another piece.

The line of the horizon was clear and hard against the sky, and in one particular quarter it showed black against a silvery climbing phosphorescence that grew and grew. At last, over the rim of the waiting earth the moon lifted with slow majesty till it swung clear of the horizon and rode off, free of moorings; and once more they began to see surfaces—meadows wide-spread, and quiet gardens, and the river itself from bank to bank, all softly disclosed, all washed clean of mystery and terror, all radiant again as by day, but with a difference that was tremendous. Their old haunts greeted them again in other raiment, as if they had slipped away and put on this pure new apparel and come quietly back, smiling as they shyly waited to see if they would be recognised again under it.

They fasten their boat to a willow and they take up exploring the riverside: hedges, hollow trees, «the runnels and their little culverts» (which are respectively a small stream and a small channel, usually like the ones allowing water to run under a road or a railroad), ditches and dry water-ways. They then embark again, cross the river, repeat, go up a bit, and repeat again. They literally canvas the riverbank, methodically as we might expect from our Sherlock-like Rat.

…while the moon, serene and detached in a cloudless sky, did what she could, though so far off, to help them in their quest; till her hour came and she sank earthwards reluctantly, and left them, and mystery once more held field and river.

The sun is rising, a bird pipes, a light breeze passes through the reeds and bulrushes (do you remember? The book was supposed to be called The Wind in the Reeds). It is at this point that, in a reverse situation compared to Dulce Domum, Rat hears a mysterious call.

“It’s gone!” sighed the Rat, sinking back in his seat again. “So beautiful and strange and new! Since it was to end so soon, I almost wish I had never heard it. For it has roused a longing in me that is pain, and nothing seems worth while but just to hear that sound once more and go on listening to it for ever. No! There it is again!” he cried, alert once more. Entranced, he was silent for a long space, spellbound.

Apparently, the particular way of describing the chant is a direct quote from Matthew Arnold‘s “Dover Beach” (1876), a poem depicting a world of nightmare and beauty.

Ah, love, let us be true

To one another! for the world, which seems

To lie before us like a land of dreams,

So various, so beautiful, so new,

Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light,

Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain;

And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night.

In his Secret Gardens, Humphrey Carpenter (who is finally done obsessing over the author’s view of sex, apparently) uses these passages to articulate a complex view of the Wind in the Willows as a complex metaphor of artistic creation and inspiration: in his view, Badger personifies pure inspiration, where Toad represents the threat posed to the artist by his own temperament, unstable personality and passions (which kind of make sense if it’s true that Toad’s escape from prison was partly modelled after the deep impression Oscar Wilde’s imprisonment had over Grahame himself). This is relevant, supposedly, because Rat is the one guiding Mole through his artistic development and therefore is the one hearing the chant of Pan, while Mole initially can’t.

“Now it passes on and I begin to lose it,” he said presently. “O Mole! the beauty of it! The merry bubble and joy, the thin, clear, happy call of the distant piping! Such music I never dreamed of, and the call in it is stronger even than the music is sweet! Row on, Mole, row! For the music and the call must be for us.”

The tale is starting to have echoes of Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream and it’s about time, since it’s precisely that night and dawn is breaking. It’s also echoing another play by Shakespeare, which gets quoted multiple times throughout the whole book: The Twelfth Night.

If music be the food of love, play on;

Give me excess of it, that, surfeiting.

Mole hears nothing «but the wind playing in the reeds», and it also makes sense if you don’t go to such complex lengths in order to understand that Pan is the manifestation of a spirit of pure nature and Mole is a novice, who has just been initiated into the mysteries and wonders of the river by Rat himself. It is no wonder he is not ready for the divine manifestation, while Rat is.

Or you could go with the simple fact that Rat is… well, a rat, and Grahame calls Pan a “piper”, probably borrowing the term from Robert Browning‘s The Pied Piper of Hamelin, written in 1842 around the folk tale character and published again in 1888 by Frederick Wayne, with illustrations by Kate Greenaway. Hers is possibly the most famous illustration of the tale and when I say “piped piper”, chances are you’re thinking about hers.

Mole is still hearing nothing, but Rat is «rapt, transported, trembling, he was possessed in all his senses by this new divine thing that caught up his helpless soul and swung and dandled it, a powerless but happy infant in a strong sustaining grasp» and, once they arrive at a fork in the river, promptly direct the companion towards the backwaters. Mole only hears the wind playing in the reeds and rushes and willows (called osiers in the first edition and then changed following the change in the title). Until they come closer, and the call becomes strong enough to penetrate even Mole’s uninitiate ears.

Breathless and transfixed the Mole stopped rowing as the liquid run of that glad piping broke on him like a wave, caught him up, and possessed him utterly. He saw the tears on his comrade’s cheeks, and bowed his head and understood.

The music is dulling their senses in a way, but also sharpening them in another. Complicit with the sun rising, the colours of nature seem more bright, the sounds are more pure: «the rich meadow-grass seemed that morning of a freshness and a greenness unsurpassable», the roses are more vivid than ever, the willow-herb is flourishing and, among the herbs Grahame mentions, we also find the meadow-sweet, a perennial herb with tiny and very scented creamy flowers, with a wide-spread ceremonial use. In was found in a Bronze Age cairn (a pile of stones used to mark a burial) at Fan Foel, in Sout-West Wales, and it was probably used to flavour mead of beer, as it suggested finding some inside a small ceramic drinking vessel from Ashgrove (Fife, Scotland), and inside another vessel from North Mains, Strathallan. In Welsh mythology, it is one of the herbs used by Gwydion and Math to create the first woman, Blodeuwedd, alongside oak blossoms and broom.

It was supposedly one of the three most sacred herbs used by druids (alongside water mint and vervain), and it’s mentioned by Geoffrey Chaucer in his Knight’s Tale, the first of The Canterbury Tales which in turn takes inspiration from Teseida (full title Teseida delle Nozze d’Emilia, or “The Theseid, Concerning the Nuptials of Emily”) by Giovanni Boccaccio.

It is also mentioned in John Gerard‘s The Herball (1576), the most prominent English botany book throughout the XVII Century, and it was the favourite scented flower of Queen Elizabeth I, who always wanted it inside her chambers.

Now that both our friends are enchanted, Mole rows towards the sound. And no birds dare to sing, as the dawn approaches, but the melody continues, steady, stronger.

The animals being silenced by a marvel is a common figure in this kind of situation, an attribute of Orpheus, and here Kenneth Grahame might have been thinking of John Keat‘s Belle Dame Sans Merci.

The sedge has withered from the lake

And no birds sing.

The two friends have arrived at the weir, the place where Otter was afraid his Portly had gone up swimming without having the skill to survive it.

A wide half-circle of foam and glinting lights and shining shoulders of green water, the great weir closed the backwater from bank to bank, troubled all the quiet surface with twirling eddies and floating foam-streaks, and deadened all other sounds with its solemn and soothing rumble.

In the middle of the man-made water trap, however, lays an Island, «embraced in the weir’s shimmering arm-spread», a small round island that almost seems temporary, a floating vessel that decided to lay anchor over there. The island is surrounded by plants and trees, «fringed close with willow and silver birch and alder», which surrounds it like a curtain, sheltering and hiding the enchantment filtering through them in the form of music.

J.M. Barrie uses similar pictures when entering the mysterious Serpentine Island with his Pan (first name, Peter) and his adventures in Kensington Gardens. But more on that later.

Reserved, shy, but full of significance, it hid whatever it might hold behind a veil, keeping it till the hour should come, and, with the hour, those who were called and chosen.

In silence, the two row upstream, surpass the small tumultuous waters of the weir and dock on the island, they push through «the blossom and scented herbage and undergrowth» and they find themselves into what can only be described as an enchanted garden: «a little lawn of a marvellous green, set round with Nature’s own orchard-trees—crab-apple, wild cherry, and sloe». Trembling and in awe, the two friends come closer and closer, until Mole feels his muscles turning to water and Rat is shivering, hit by the divine appearance.

Perhaps he would never have dared to raise his eyes, but that, though the piping was now hushed, the call and the summons seemed still dominant and imperious. He might not refuse, were Death himself waiting to strike him instantly, once he had looked with mortal eye on things rightly kept hidden. Trembling he obeyed, and raised his humble head; and then, in that utter clearness of the imminent dawn, while Nature, flushed with fullness of incredible colour, seemed to hold her breath for the event, he looked in the very eyes of the Friend and Helper.

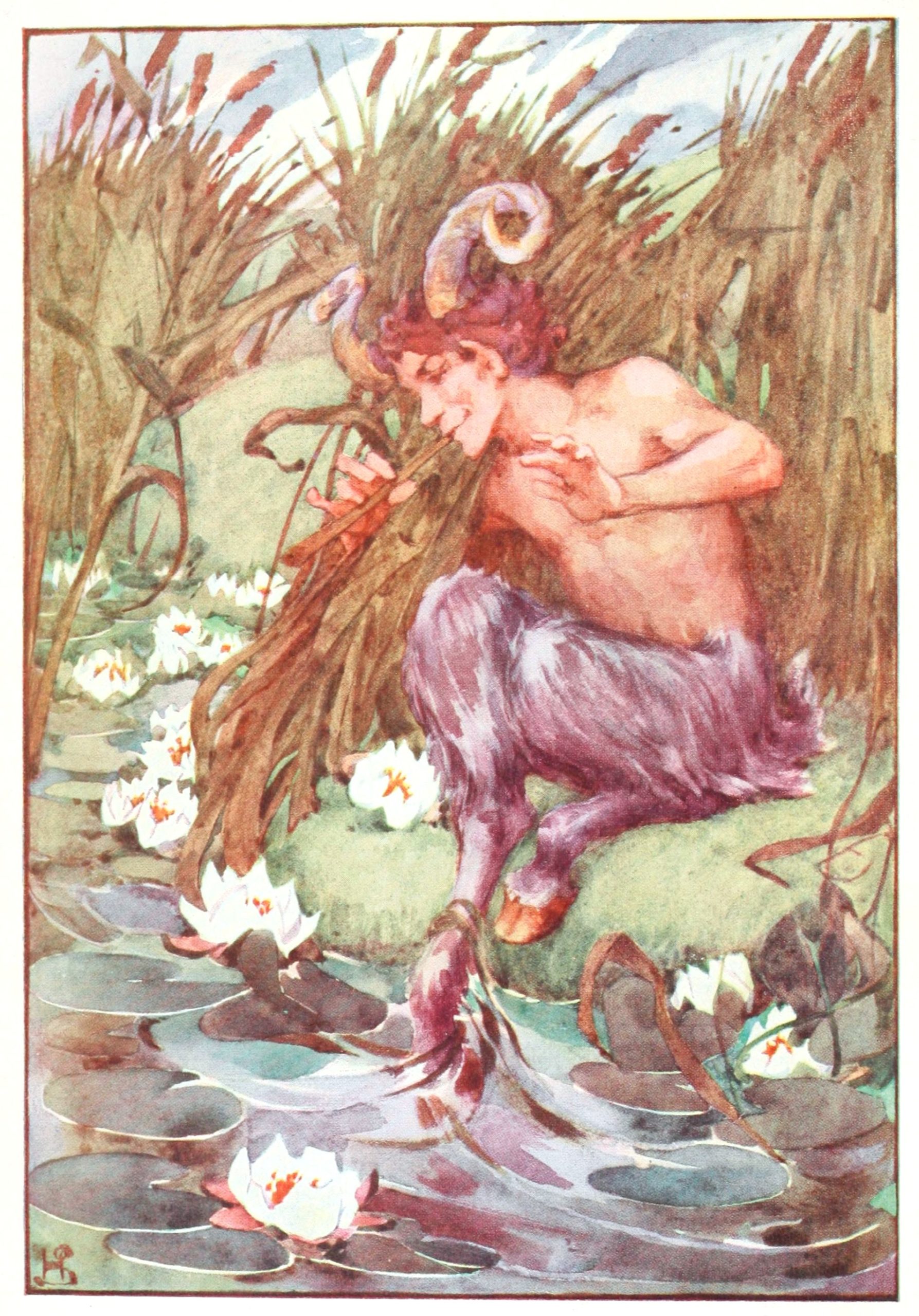

Pan’s description is rather precise: the curved horns with their backward sweep; a stern, hooked nose between humorous and kind eyes looking down to them, a half-smiling bearded mouth, «the splendid curves of the shaggy limbs disposed in majestic ease on the sward». And, between his hoofs, little Portly is laying asleep, «the little, round, podgy, childish form of the baby otter».

“Afraid! Of Him? O, never, never! And yet—and yet—O, Mole, I am afraid!”

The sun rises, its beams strike our two animals blinding them and then, just like that, the vision is gone.

The two animals just have a moment to contemplate the misery of having gazed upon such a vision and having lost it: a gentle breeze comes through, caressing the aspens and the dewy roses, and in reaching their faces it grants them one more gift: the gift to forget what they have seen, «the last best gift» of the kind demi-god.

Lest the awful remembrance should remain and grow, and overshadow mirth and pleasure, and the great haunting memory should spoil all the after-lives of little animals helped out of difficulties, in order that they should be happy and light-hearted as before.

Pan never gets mentioned by name and, just like that, he disappears. Rat and Mole find themselves waking up from a sort of dream and Rat seems to be the one recovering more quickly from it or, at least, so it seems from Mole’s point of view.

But Mole stood still a moment, held in thought. As one wakened suddenly from a beautiful dream, who struggles to recall it, and can recapture nothing but a dim sense of the beauty of it, the beauty! Till that, too, fades away in its turn, and the dreamer bitterly accepts the hard, cold waking and all its penalties; so Mole, after struggling with his memory for a brief space, shook his head sadly and followed the Rat.

Rat is the first to spot little Portly – or, we should say, to spot him again after the figure has disappeared – and runs towards the little lad, while Mole still struggles to wake up. Portly wakes up «with a joyous squeak», but he doesn’t seem to have received the same blessing Rat and Mole have or, just as Mole is more childish and struggling more to get rid of the vision, Portly who is a literal child is finding it very hard to get the divine apparition out of his head. This idea that children are closer to Faerie, as we have seen in Dulce Domum, is rather frequent in Victorian literature.

As a child that has fallen happily asleep in its nurse’s arms, and wakes to find itself alone and laid in a strange place, and searches corners and cupboards, and runs from room to room, despair growing silently in its heart, even so Portly searched the island and searched, dogged and unwearying, till at last the black moment came for giving it up, and sitting down and crying bitterly.

While Rat is inspecting the grass, trying to figure out which kind of animal has been here, Mole comforts little Portly and prompts Rat to bring him back to his father. They convince the little one to go back to the boat, which looks to him like a treat, and row back.

The sun was fully up by now, and hot on them, birds sang lustily and without restraint, and flowers smiled and nodded from either bank, but somehow—so thought the animals—with less of richness and blaze of colour than they seemed to remember seeing quite recently somewhere—they wondered where.

They reach the fork again and turn upstream, towards the ford, where they know Otter is holding vigil. And then they do something very sweet: they set the child up to his feet, give him directions and wait secretly as he reaches his father and the two hug again. They stay on the side, secluded, not wanting to take the credit for saving the child.

They turn back, then, and they are feeling strangely tired, with the distinctive feeling that «something very surprising and splendid and beautiful» has happened. The wind is playing in the reeds (changed to willows) and this is the part giving the title to the entire book. Mole listens to the wind and Rat tries to interpret the music still echoing among them. In his proper role as a bard, he puts them to words.

Lest the awe should dwell—

And turn your frolic to fret—

You shall look on my power at the helping hour—

But then you shall forget!—forget, forget—

Lest limbs be reddened and rent—

I spring the trap that is set—

As I loose the snare you may glimpse me there—

For surely you shall forget!Helper and healer, I cheer—

Small waifs in the woodland wet—

Strays I find in it, wounds I bind in it—

Bidding them all forget!

Pan in literature

Pan firstly appeared in Grahame’s first book, Pagan Papers, a collection of light stories he wrote in his youth and published in 1893. In 1895 these stories took the form of a better-known collection, called The Golden Age and followed by Dream Days in 1898, a collection that also contains another story that Disney adapted into a short cartoon: The Reluctant Dragon. Within Pagan Papers, one of the stories is “The Rural Pan” and in that story, written as early as 1891, we find lots of the elements we’ll find again in The Wind in the Willows: a “sinuous Mole” meets with “his foster-brothers the dab-chick and water-rat”.

«Both iron road and level highway are shunned by the rural Pan, who chooses rather to foot it along the sheep track on the limitless downs or the thwart-leading footpath through copse and spinney, not without pleasant fellowship with feather and fir. Nor does it follow from all this that the god is unsocial. Albeit shy of the company of his more showy brother-deities, he loveth the more unpretentious humankind, especially them that are adscripti glebe, addicted to the kindly soil and to the working thereof: perfect in no way, only simple, cheery sinners. For he is only half a god after all, and the red earth in him is strong. When the pelting storm drives the wayfarers to the sheltering inn, among the little group on bench and settle Pan has been known to appear at times, in homely guise of hedger-and-ditcher or weather-beaten shepherd from the downs.

Strange lore and quaint fancy he will then impart, in the musical Wessex or Mercian he has learned to speak so naturally; though it may not be till many a mile away that you begin to suspect that you have unwittingly talked with him who chased the flying Syrinx in Arcady and turned the tide of fight at Marathon.

Yes: to-day the iron horse has searched the country through—east and west, north and south—bringing with it Commercialism, whose god is Jerry, and who studs the hills with stucco and garrotes the streams with the girder. Bringing, too, into every nook and corner fashion and chatter, the tailor-made gown and the eye-glass. Happily a great part is still spared—how great these others fortunately do not know—in which the rural Pan and his following may hide their heads for yet a little longer, until the growing tyranny has invaded the last common, spinney, and sheep-down, and driven the kindly god the well-wisher to man—whither?»

Pan is a prominent figure in the Romantic movement and recurs a lot in Victorian and Edwardian literature. We find poems like “The Rebirthing of Pan” by Adrian Eckersley, “Pan’s Pipes” by Robert Louis Stevenson, “Pan with Us” by Robert Frost, and “The Death of Pan” by Lord Dunsany. Pan appears in H.H. Munro‘s The Music on the Hill (1911) and in E.M. Forsters‘s The Little White Bird (1902), named after J.M. Barrie‘s first Peter Pan story. John Keats takes inspiration from Elizabethan poets and opens his Endymion with a festival dedicated to Pan.

A thing of beauty is a joy for ever:

Its loveliness increases; it will never

Pass into nothingness; but still will keep

A bower quiet for us, and a sleep

Full of sweet dreams, and health, and quiet breathing.

Things went further than that: around XVIII Century, a group of gentry folks led by Benjamin Hyett had the great idea of starting a Pan cult, in the not-so-exotic town of Painswick, Gloucestershire. They organized annual processions dedicated to Pan and brought about, he erected temples and decorations, and even built a “Pan’s lodge” overlooking the valley. They were so convincing that in 1885 the new vicar W.H. Seddon, after the tradition had been dead for no more than 50 years, believed it to be original and tried to revive it. Pan’s statue was buried in 1950, by the new vicar.

Edwardian Literature

In her master thesis And did those Hooves – Pan and the Edwardians, Eleanor Toland collects a huge amount of works from this period, in which Pan makes an appearance as a helper or as a prominent figure, or in which the figure of Pan is used to evoke Faerie and a magical pastoral pre-industrial setting: alongside Barrie’s Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, a work that in my opinion surpasses by far the much more famous Peter Pan and Wendy, we find:

- “The Story of a Panic” by E.M. Forster, firstly published in The Celestial Omnibus (and other stories) (1911) and then in Collected Short Stories (1947), in which Pan is a terrifying figure but ultimately presents himself as a liberator for those strong enough to accept his gifts;

- “The Man Who Went Too Far” by E.F. Benson, a story even H. P. Lovecraft mentions in his essay “Supernatural Horror in Literature“, and in which Pan represents a fascinating but terrifying communion with nature: it’s a ghost short story collected in his The Room in the Tower, and Other Stories (1912) in which Frank, an English gentleman, rejects Christian orthodoxy;

- The Dance of Death by Algernon Blackwood, published in The Dance of Death and Other Tales (1927), for which you can read a review here;

- stories like “The Death of Pan” in Fifty-One Tales by Lord Dunsany, and in his The Blessing of Pan (1927);

- All-Fellows: Seven Tales of Lower Redemption by author and playwriter Laurence Housman, who wrote several of these fairy-tales for children, mixing pagan features with Christian subtexts in this weird idea Edwardian literature had of mixing Pan with Christ (Toland dedicates to this nuance a whole chapter of her thesis);

- the famous horror story The Great God Pan (1890) by Arthur Machen, praised by Stephen King in 2008 as «…maybe the best in the English language»;

- the supernatural thriller The Magician (1908) by William Somerset Maugham, which became a novel in 1926 and resulted in a highly unamused Aleister Crowley (the main character is based on the British occultist);

- The Enchanted Castle (1907), a children’s fantasy novel by Edith Nesbit in which three children spend their summer holidays at a castle, surrounded by magical statues which come to life in the moonlight, and only they can see divine appearances such as a youthful Pan;

- The Garden God: A Tale of Two Boys by Forrest Reid, one of the most revolutionary authors for children alongside Hugh Walpole and J.M. Barrie: his story is the love between two young men, resulting in the end of one, and considered by the author himself one of the worst things he had ever written (unclearly whether it was because of the explicit homosexual theme or because the death of one of the two lovers was widely interpreted as a punishment for their “sins”);

- a comic novel by James Stephens, The Crock of Gold, published in 1912 and in which Pan is holding captive the most beautiful woman in the world, Cáitilin Ni Murrachu, with Aengus Óg as his accomplice.

She also mentioned books in which you find what she calls “Pan figures”:

- The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett, in which we find Dickon, a helper;

- The Man Who Was Thursday: A Nightmare by G.K. Chesterton, a theological novel in which we find the character of Sunday and in which the figure of Pan is merged with Christian figures.

Pan in Art

Following its revival in romantic literature, art quickly followed.

Edward Burne-Jones was one of the authors who mostly focused on the subjects, most notably with his Pan and Psyche (1870s, firstly exhibited in 1878, now at the Harvard Art Museum), and his The garden of Pan (1886-1887). Around the same time, the French painter Émile Jean-Baptiste Philippe Bin was doing this Pan’s slumber and you can see how far behind he was.

The Swiss symbolist painter Arnold Böcklin also dabbled in the subject, with his Pan and the Dryads (1897), his Pan Dancing with Children (1884), the Sleeping Diana Watched by Two Fauns (1877), his Faun, blowing the syrinx, also called Idyll or Pan Amidst Columns (1875), the Two fishing Pans (1874), his Faun whistling to a Blackbird (1865, but check out the beautiful second version), his Pan terrifies a shepherd (1860), and my favourite: Pan in the Reeds (1858).

Other artists around the same time include Dutch painter Adolphe Alexandre Lesrel, who did this Pan and Venus around 1865, this rather unsettling Pan by Russian author Mikhail Vrubel, and Ernst Klimt, the younger brother of Gustav, who did this Pan Consoling Psyche in which Pan is clearly someone’s old and not-so-there uncle.

Edward Reginald Frampton also tried his hand on the topic: there’s a study for The voice of Pan (1910), around the same time he did this Fairyland, but I am unclear on what it was supposed to be used.

Frederick Leighton also gives us a very humanized Pan, with a quote from Keats’ Endymion.

‘O thou, to whom

Broad leaved fig trees even now foredoom

Their ripen’d fruitage’

Among all these authors, it’s worth mentioning John Reinhard Weguelin, an English painter and illustrator who did amazing stuff very much in the same style of John William Waterhouse (but his girls are a lot less dressed): among his works, the ones which best describe the magic pastoral feeling induced by Pan in the Wind in the Willows are A Pastoral (1905), Pan the Beguiler (1898) in which our favourite God is charming two mermaids, and The Magic of Pan’s Flute (1905) in which a dryad emerging from a tree is charmed by a Pan who turns his back on us.

Pan is also the favourite subject matter for covers, especially of magazines, and German Jugenstile is absolutely obsessed with him. Hans Pfaff puts him on the cover of Jugend for May, 30th 1896 and from 1896 to 1900 the German published Otto Julius Bierbaum published a literary magazine named after the demi-God, for which we had designs by Arnold Böcklin (Sirene, 1897), Joseph Sattler and Ludwig von Hofmann.

Pan is also on the cover of Jean Lang‘s A book of myths (1915), designed by Helen Stratton.

Walter Crane also illustrated Pan as one of the plates for The story of Greece: told to boys and girls (1910s) by Mary Macgregor. The plate’s subtitle reads:

Sweet, piercing sweet was the music of Pan’s pipe

If you’re looking for some real unsettling stuff, you can also try and check out Wilhelm von Gloeden‘s set of photographs The Great Faun.

This is one of my favourite chapters in all literature. Thank you for this thread.

Charlotte