The Caterpillar

This is going to be a long one, because we’ve finally arrived at Chapter V (yeah, we’re still just at chapter V) and we meet one of the most beloved characters in the tale: the caterpillar. To be fair, as it often happens with Carroll, the actual introduction of the character is done at the […]

This is going to be a long one, because we’ve finally arrived at Chapter V (yeah, we’re still just at chapter V) and we meet one of the most beloved characters in the tale: the caterpillar.

To be fair, as it often happens with Carroll, the actual introduction of the character is done at the end of the previous chapter, when Alice manages to run off from the giant puppy and finds a large mushroom, about the same height of Alice herself.

She stretched herself up on tiptoe, and peeped over the edge of the mushroom, and her eyes immediately met those of a large blue caterpillar, that was sitting on the top, with its arms folded, quietly smoking a long hookah, and taking not the smallest notice of her or of anything else.

The fame of the caterpillar is due to many different reasons: the striking pictures Carroll uses for him, hookah included, and the existential crisis he’s able to plunge Alice into. A transformative creature, he’s like the opposite of what she’s going through right now: he knows what he is, he knows what he’s going to become, although in the book we don’t really get to see the transformation, and he’s unbothered by pretty much everything. He is probably the first helper we meet, the first character who seems to know what the fuck is going on in Wonderland.

“Who are you?” said the Caterpillar.

There’s a shitload of illustrations and it would be difficult to include them all, but there are few groups we can identify, starting with variants from Carroll’s description and the first one is, oddly enough, starting from Carroll’s own illustration. Some illustrations you can also find here.

Variant 1: not a hookah

Carroll himself illustrated the character and his illustration is creepy as hell, with the hookah illustrated more like a very long pipe with thick black smoke coming out of it.

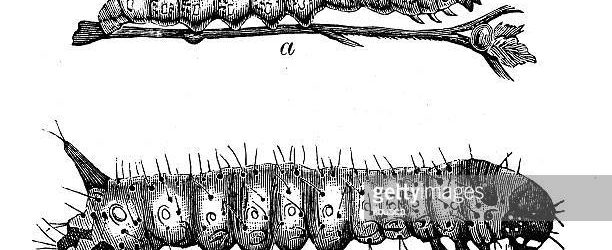

This influenced other artists who either wanted to homage the original or had never seen a hookah in their entire life. It’s the case of Bessie Pease Gutmann, the one who usually gives us one of those puffy, baby-faced Alices, who clearly had more knowledge of flowers, mushrooms and… well, caterpillars. Hers is one of the most realistic (and hence disgusting) portrayal of this much-beloved character.

Among modern illustrators, one of the most cosy (and less hookah-y) caterpillars is Lisbeth Zwerger‘s, who recreates a complete house on top of the mushroom: we have a bottle of wine, a low table with a book on it (and now I’m dying to know what is he reading), a garden chair. You can see another book next to the pink side table and in one of the hands our caterpillar has a glass of wine.

Lisbeth Zwerger is an Austrian illustrator and she worked on several books for children or adaptations of books for children, like Andersen’s Tales and Dickens’ Christmas Carol. She also illustrated the The Tales of Beedle the Bard from Fucking-Transphobic-She-Who-Must-Not-Be-Named.

Variant 2: the Green Caterpillar

The same decorative use of the hookah’s pipe as in Tenniel’s illustration (a Proper Caterpillar, as we’ll see further on) is then reprised by Thomas Maybank, in the cover of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland Retold in Words of One Syllable. It’s a book we haven’t talked about, yet: published by Burt in 1905 in a series of books like that, it’s a retelling by J.C. Gorham in which a simpler language is used. Which is quite silly and weird, considering that the book was originally written for a child. The cover of the first edition featured Alice with the white rabbit, by J. Watson Davis: this seems to be a later one (thanks to this tweet).

Another green caterpillar is provided by Helen Jacobs, who illustrated an Alice in Wonderland retold by Constance M. Martin and published by Philip & Tacey.

You can find a biography of this artist, alongside some illustrations, on this website: she worked on some beautiful inked drawings for The Wild Swans and other stories (a collection of Hans C. Andersen’s works), for a Little Mermaid retold by the same Constance M. Martin and for a King Arthur and his Knights, also retold by Martin.

Her caterpillar is quite polite, with a human face a couple of human arms, ending in sleeves, with two very human hands.

For some reason, Mabel Lucie Attwell decides to go green too. Her Caterpillar looks more like a slug and, although frankly overdressed, he features more appropriately in this section. He’s looking at Alice, but she doesn’t seem to be paying any attention and she’s looking at us. I’m not fond of the round, reassuring illustrations from this artist, but this is definitely one of her weirdest pieces, which makes it one of the few I find interesting.

Another lady illustrator to go green was Evelyn Stuart Hardy (1908), who published by John F. Shaw. I was not able to find a bigger picture, but there are striking similarities between this caterpillar’s style, with the green body, the brown head and the red hat, and Attwell’s.

W.H. Walker‘s caterpillar is between greenish and blueish, but I figured he would find himself in good company in this section, with all his companions with a red fez.

The work of this illustrator was published by John Lane in at least five different binding variants (leather, suede, blue cloth and paper-covered boards). I already featured one of his illustrations in the falling Alice post, I believe, and a hardcover edition is on sale here.

The Proper Caterpillar: hookah and all

Of course, one of the most important illustrations is by John Tenniel and this one had a great influence on the Disney version too. He gets the hookah right and he puts lots of love into it, for once, with delicate circles of the tube framing the caterpillar’s body. It’s probably one of the most beautiful illustrations of the whole book.

According to Martin Gardner’s Annotated Alice, Carroll didn’t really like the Caterpillar’s nose and chin in Tenniel’s drawing and explains that they are really two of its legs.

«And do you see its long nose and chin? At least, they look exactly like a nose and chin, don’t they? But they really are two of its legs. You know a Caterpillar has got quantities of legs: you can see more of them, further down.»

The Nursery “Alice” (1966)

Arthur Rackham, our beloved illustrator from where everything started months ago, also illustrates a caterpillar with a distinctively human face, but he’s not a bit shy about it. He also gives him a little wig, like a judge hearing out a witness or, most likely, passing judgment on one awaiting trial.

There’s a lot of other “proper” caterpillars and I don’t dream to be able to list them all, so I’ll give you some from artists we haven’t met yet.

One of them is Hume Henderson, who was published by Readers Library around 1928. He puts the caterpillar in the cover, as you can see below, and his Alice has a strong vibe from the “jazzy” one. The cover of the book can be found here.

Among more recent artists, Helen Oxenbury also gives us a realistic caterpillar, even too realistic for my taste, but it doesn’t seem to bother her little Alice. Children would be children. The colours, as usual, are stunning. And you have to appreciate the painful attention to the mushroom details.

Another artist we haven’t met yet is Libico Maraja, a wonderful Swiss-born Italian painter. You can take a look at his work here. This illustration is very cartoonish, but his other works are more interesting.

The Overdressed Caterpillar

Sometimes caterpillars are cute, sometimes they’re creepy. Sometimes you get the feeling we and the illustrator mean two very different things by “caterpillar”. And sometimes, regardless of Carroll’s description, the illustrator puts a great deal of attention into the Caterpillar’s attire.

Blanche McManus, the artist illustrating the first American editions by Mansfield & Wessels (1899) with her red and green colours, gives us a caterpillar complemented with a fez, probably to go with the hookah.

T.H. Robinson, who usually gives us such ornate and beautiful sheets, goes gloomy and sad, for this caterpillar, but the clothes hide his figure a lot and we wouldn’t know it’s a caterpillar if the text did not tell us. I don’t know what’s going on with the fleshy fingers on the chin, so do not ask.

But the real fashion victim is Millicent Sowerby‘s caterpillar: with a night gown and a perplexed look, he was clearly enjoying his evening meditation before going to bed. You have to love the facial expression and the two antennas that look a bit like eyebrows.

Another weird one is by Gwynedd M. Hudson (1922), published by Hodder & Stoughton, who copies a bit of Rackham’s caterpillar – with the wig and everything – but goes freestyle on the multicoloured decors for his sprouts of fur. It’s no surprise, since this was the same artist who gave us a very fancily dressed white rabbit in the very first sections of the story.

Margaret Tarrant (1916) also gives us a fancy caterpillar, with big white puffy sleeves and a Pierrot-style neckpiece. As usual, one of the most interesting things in this illustration, to me, is the composition of the background.

Harry Rountree picks up on lots of this vibes and he gives us a blue-clothed green caterpillar, with a handkerchief around his neck, a red fez and, as Disney will do a couple of decades later, several pairs of oriental-looking shoes. He’s trying to avert our attention from the fact that he has clearly never seen a hookah in his entire life.

The most exaggerated caterpillar of all, however, is provided by D.R. Sexton, and published by Shaw in 1933. We haven’t met this illustrator yet and I couldn’t find any meaningful information aside from a bunch of Pinterest pages (have I already mentioned how much I despise Pinterest, in this post?), but this caterpillar is quite a piece of work. Aside from the nipple-like arms, which are quite creepy, the turban is awesome and I am definitely going to steal that sash and gown. He can keep the shoes, albeit undoubtedly stylish.

Amongst more contemporary artists, we find Peter Weevers, who gives our caterpillar a completely human face (probably a humoristic impression of someone, but I have no idea who that is) with a worn sleeveless jacket and a fez as you might see in a badly arranged cartoon on middle-east. For some reason, a flame is burning vividly on top of the hookah, which means the tobacco is on fire, and I suggest you never to that. That’s not the point of a hookah.

Tove Jansson is also providing us a caterpillar in a very particular style, with a face that might remind you of her most famous creations: the moomins.

This drawing is a good example of the style and colours she used in illustrating this and other books. We also saw something of hers with the overgrown Alice inside the rabbit’s house.

The Furry Caterpillar (and other weird shit)

Millicent Sowerby was published by Chatto & Windus in 1907, and then she reached overseas with an edition by the joint venture Duffield/Chatto & Windus, one year later. For these books she did twelve illustrations, but she then produced a second set of eight for a new edition by Henry Frowde/Hodder and Stoughton (London, 1908). I unfortunately do not know yet from which set did this caterpillar come.

Peter Newell, who was published by Harper USA in 1901 and whom I have neglected to mention in the past posts, gives us a cute baby-faced caterpillar with a mohawk. I’m not usually fond of his illustrations, but this one is definitely over the top.

The Caterpillar and Alice looked at each other.

The same goes for Fanny Y. Cory, who also goes for a cute, furry, round-faced caterpillar but also gives him a pair of creepy human arms. I was able to fetch a couple of illustrations from her, one with the encounter and another one, on page 57, when the caterpillar expresses boredom at Alice’s troubles.

The Caterpillar yawned once or twice…

There’s also some weird shit, out there, and we’re not prepared to see it all.

Some weird caterpillars, however, come from pre-war illustrators and it would be negligent of me not to offer them to you.

One of the weirdest is probably by Harry Furniss, published in Arthur Mee‘s The Children’s Encyclopædia between 1908 and 1909. The publication was a periodic, featuring pieces on different subjects such as geology, biology and astronomy, but there were also some narrative sections such as the Famous Books section by John Hammerton and the Stories section by Edward Wright. I’m unclear in which section and issue this caterpillar was featured, but it’s definitely the stuff of nightmares.

Furniss was an Irish-born British illustrator who worked on several magazines including the famed Punch and fully illustrated another one of Carroll’s novels, Sylvie and Bruno. He illustrated the complete works of Charles Dickens and William Makepeace Thackeray, which is quite a lot, and upon moving to the United States he also pioneered some animated works.

Slightly less unsettling, but still weird as hell, is the caterpillar designed by Walter Hawes for his Scott edition. Will anyone be able to explain me why this caterpillar looks like a spectral tarsier?

Last but not least, Justin Todd‘s caterpillar is… well, I would say it’s “realistic”, but I would have to take a closer look at actual caterpillars, to tell you that, and I am not going to do that.

Angel Dominguez‘s illustration is equally unsettling, to me, but that’s just because I hate bugs. Still, it’s funny: the caterpillar has a human face (though it might take you a while to see it) and his ass looks a little more like a dog, but it’s funny the way he’s leaning forward in an accusatory way (and the way Alice is standing her ground). There’s also a soldier ant, a very angry beetle, and I’m not sure I want to zoom in to see what’s the wasp been reading.

Surreal Caterpillars

There’s even weirder stuff, especially if you go and look amongst the less traditional artists, and of course we have to start with Salvador Dalì. The caterpillar on top of the mushroom is definitely green, but he’s showing off a sort of astral projection which is positively glorious.

It’s not the only weird caterpillar we can find and, oddly enough, not even the weirdest.

Leonard Weisgard was an American-born illustrator who spent most of his childhood in England and both wrote and illustrated books for children. You can find extensive information about him here, on a website put together by his sons.

He illustrated Alice in Wonderland in 1949, although the edition doesn’t appear in the bibliography of the website I just provided. His style is very similar to the visionary approach of Mary Blair, the concept artist behind several visions in Disney’s 1951 adaptation of Alice. And his caterpillar looks a lot more like a fish.

Another weird one, definitely less happy and far more unsettling, is Barry Moser‘s: it’s a creature resembling more the brood mothers of science fiction, it’s by far the scariest thing I’ve seen in a while and I’m going to have nightmares.

Less scary, but equally trippy, is Ralph Steadman’s caterpillar. You might remember him for his very British white rabbit with the bowler hat and here we have a creature that looks covered in a patched up blanket and is clearly a drug addict. Alice lurks from behind as if she’s meditating to murder him or, at least, push him down the mushroom and run away.

In Carroll’s drawing of hookah they are hookahs that look like it.

I think it looks more like an opium pipe, don’t you?

My mom saids hookahs can look like that in Africa.