The Wind in The Willows (5): Dulce Domum

The fifth chapter of the story, often omitted too the selections that only wish to deal with Toad and his adventures and sometimes presented in itself as a Christmas Tale, so I have decided to give it to you today, as we’ll officially end the Christmas period in this day and I am so very […]

The fifth chapter of the story, often omitted too the selections that only wish to deal with Toad and his adventures and sometimes presented in itself as a Christmas Tale, so I have decided to give it to you today, as we’ll officially end the Christmas period in this day and I am so very sad about it.

It starts pretty much as chapter IV has ended, though not at the same time: Rat and Mole are returning across country from an exploration adventure with their friend Otter who, as we have seen, is depicted with all the attributes of gentlemen adventurers such as Sir Richard Burton or T.E. Lawrence.

The title of the chapter is the latin Dulce Domum, literally “home sweet home”, and Grahame picks it as a homage to several romantic influences: it is the title of chapter 41 in Sir Walter Scott’s Waverly and a poem by T.W.H. Crosland, a painting by John Atkinson Grimshaw and a tune composed by Robert Ambrose in 1876, to name only some of them. It is also the holiday song of Winchester College, allegedly written by a boy while he was tied to a pillar as detention punishment during Whitsun (the White Sunday celebrated in May).

Our two friends are strolling through a meadow, messing with sheep, and walking uplands, a word that gets used a lot in describing England country outside of towns. It’s a term that we find codified in Jane Austen’s novels and in Thomas Hardy’s descriptions, especially in Tess of the d’Ubervilles (1891) and Jude the Obscure (1895).

They soon find themselves on what is described as «a well-metalled road» and, though one might be led to consider it a railroad, it is probably referring to a paved road where carts are travelling (the wheels of carts were made of iron). There’s evidence of this particular road being inspired by the Ridgeway, at least how it’s described by Thomas Hughes in The Scouring of the White Horse, or The Long Vacation Rumble of a London Clerk.

This road which we are upon is the Ridgeway, one of the oldest roads in England. How far it once extended, or who made it, no man knows; but you may trace it away there along the ridge of the downs as far as you can see, and in fact there are still some sixty miles of it left. But they won’t be left long, I fear… miles of it have been ploughed up within my memory. God meant their doin, Sir, for sheep walks, and so our fathers left them.

Of course animals such as Mole and Rat care not for villages, though we have seen them being able to go to a railway station and take a train, nor they like highways (understandably, considered the misfortune with Toad’s gipsy wagon), and they are most likely to take another road: they do not take advantages of the church, the post office, the public-house, they are an independent and separate society.

It is snowing, and the way the village is described echoes a similar scene in Dickens’ A Christmas Carol:

A light shone from the window of a hut, and swiftly they advanced towards it. Passing through the wall of mud and stone, they found a cheerful company assembled round a glowing fire. An old, old man and woman, with their children and their children’s children, and another generation beyond that, sll decked out gaily in their holiday attire. The old man, in a voice that seldom rose above the howling of the wind upon the barren waste, was singing them a Christmas song.

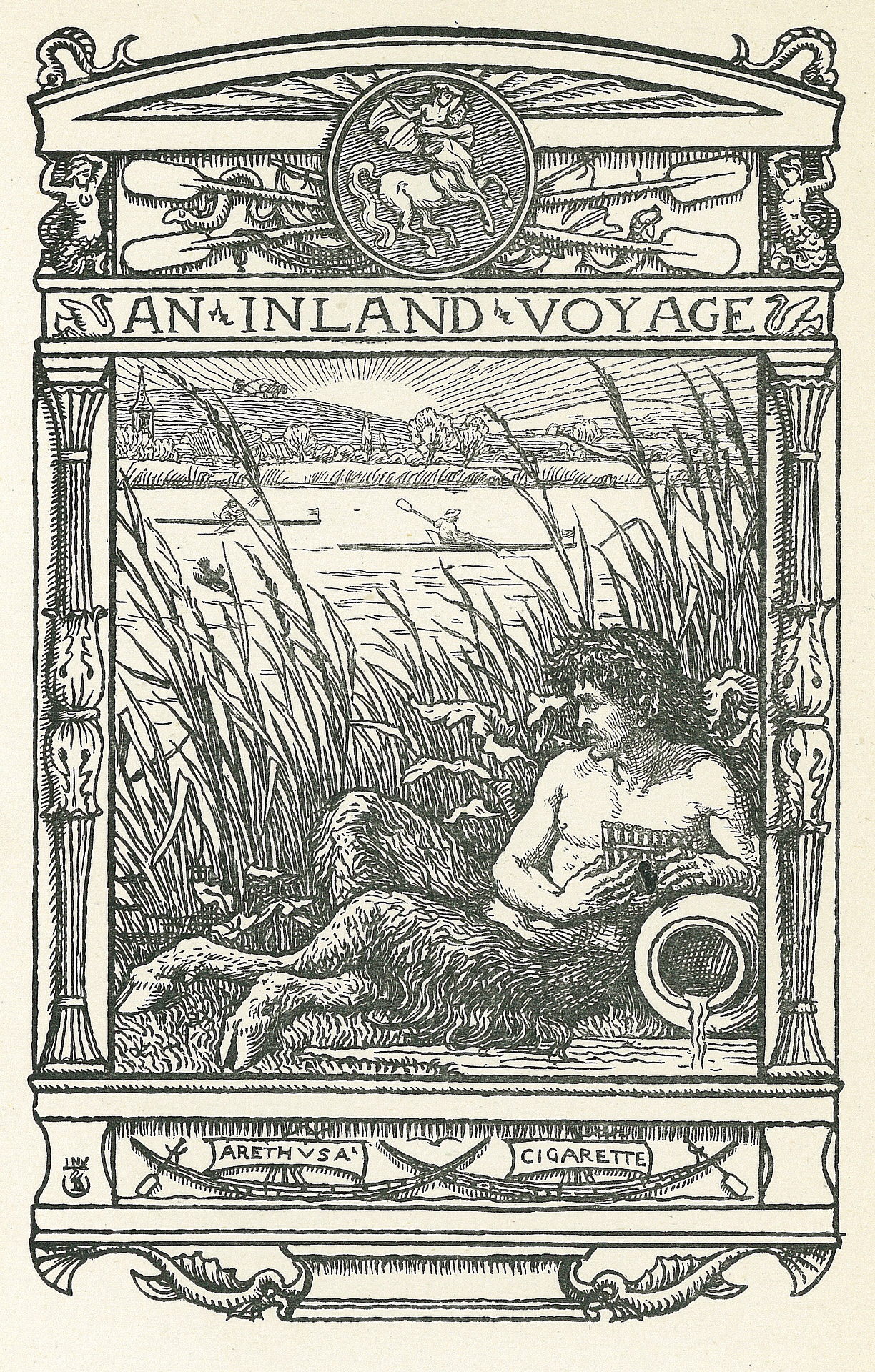

Another possible inspiration is Robert Louis Stevenson’s little-known and absolutely delightful An Inland Voyage, an account of his boating travels from Antwerp to Brussels. He drafted it in 1876 and it precedes Travels with a Donkey in the Cévennes (1879) and The Silverado Squatters (1883). The voyage was undertaken by Stevenson with his friend Sir Walter Grindlay Simpson, on board of two weird contraptions that basically were canoes with sails, named Arethusa and Cigarette. They were both fond of peering through the curtainless windows of Holland and France.

…and the windows grew brighter as the night increased in darkness. We crudged in and out of La Fere streets; we saw ships, and private houses, where people were copiously dining; we saw stables where carters’ nags had plenty of fodder and clean straw.

Just as Stevenson in his barging, the two venture inside the village, at Rat’s suggestion.

“At this season of the year they’re all safe indoors by this time, sitting round the fire; men, women, and children, dogs and cats and all. We shall slip through all right, without any bother or unpleasantness, and we can have a look at them through their windows if you like, and see what they’re doing.

It is mid-December and the two approach the village with light feet, peeking through the windows and seeing people gathered round the tea-table, absorbed in handiwork or talking with laughter and happy grace. We find again the bird-cage motive and Rat and Mole behaves as if they’re at the theatre, though Shepard draws them at the movies instead.

It is when they leave the village that Mole, whom we have seen at the very beginning of the take being visited by the call of Spring, gets one of his «mysterious fairy calls, from out the void that suddenly reached Mole in the darkness, making him tingle through and through with its very familiar appeal, even while yet he could not clearly remember what it was».

«We others, who have long lost the more subtle of the physical senses, have not even proper terms to express an animal’s inter-communications with his surroundings, living or otherwise, and have only the word “smell,” for instance, to include the whole range of delicate thrills which murmur in the nose of the animal night and day, summoning, warning, inciting, repelling».

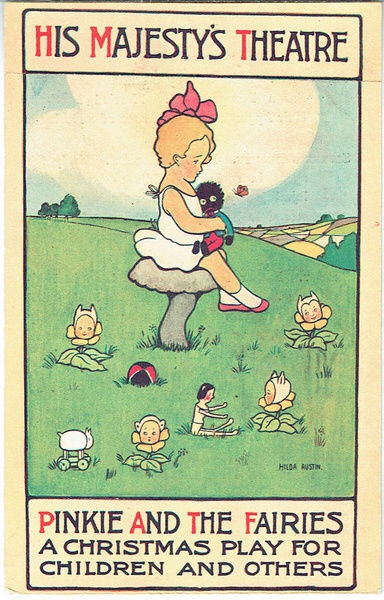

Mole is a bit like the children in Barrie’s works or in a play by one of Grahame’s closest friends, Graham Robertson, author, painted and illustrator. He was was a collector of art, particularly fond of William Blake, and he donated a considerable collection of works to the to the Tate Gallery in London. He designed costumes for Sarah Bernhardt and Ellen Terry, and could count among his acquaintances and frequentations lots of different artists, including Oscar Wilde. He painted too, and he himself was painted twice by John Singer Sargent. Among the books he wrote and illustrated, A Masque of May Morning, A Year of Songs for a Baby in a Garden, but he also did illustrations for other’s works, such as Pan’s Garden by Algernon Blackwood.

In 1908, Robertson wrote a child’s play titled Pinkie and the Faeries, first produced at His Majesty’s Theatre on December 19th, 1908, with a rather unsettling poster art by Hilda Austin, who choose to give us a child on top of a mushroom, hugging a questionable doll. The author personally believed fairy existed, just as other authors of his time such as Conan Doyle, and that their language could best be heard by children.

In our scenario, Mole is closer to the supernatural call, just because he is closer to where his house was. The house, that we have briefly seen in the first chapter, here is personified and behaves like a character.

Home! That was what they meant, those caressing appeals, those soft touches wafted through the air, those invisible little hands pulling and tugging, all one way! Why, it must be quite close by him at that moment, his old home that he had hurriedly forsaken and never sought again, that day when he first found the River! And now it was sending out its scouts and its messengers to capture him and bring him in.

The message his house is sending him, the strange sensation, is described as «telegraphic current». Mention of the telegraph, which was already obsolete in Grahame’s times, is only another way of being nostalgic and set his tale in an undefined previous Era.

Mole’s longing gets so fierce that Rat cannot help but ask what is wrong with him and he, in turn, doesn’t dare to speak, for fear of offending his friend. Mole’s feelings are described with the same words used in the Odyssey, when Ulysses doesn’t dare to tell his hosts how much he misses home, not to offend their hospitality.

Meanwhile he lives and grieves upon that island

in thralldom to the nymph;

he cannot stir, cannot fare homeward,

for no ship is left him

In Mole’s recollection, his house still isn’t much and we are told that he made it for himself: still, albeit shabby and poorly furnished, it had been a good place to return to, after a day’s work.

And the home had been happy with him, too, evidently, and was missing him, and wanted him back, and was telling him so, through his nose, sorrowfully, reproachfully, but with no bitterness or anger; only with plaintive reminder that it was there, and wanted him.

The pull is too strong and Mole has to tell Rat, but his good friend is too preoccupied with the road. They carry on, to Mole’s dismay, until he breaks down in a hysterical tearful and sobbing crisis.

As soon as he speaks up, Rat gets angry at himself, calling himself a pig and upsets Mole in return, but he is only resolving to help his friend finding his lost home, and in accompanying him. Arm in arm, the two venture forth, led by Mole’s nose, and at last they find it.

Suddenly, without giving warning, he dived; but the Rat was on the alert, and promptly followed him down the tunnel to which his unerring nose had faithfully led him.

The scene is a lot like Alice in Wonderland’s “Down the Rabbit Hole”.

Alice ran across the fields after [the rabbit], and was just in time to see it pop down a large rabbit-hole under the hedge.

In another moment, down went Alice after it, never once considering how in the world she was to get out again.

The rabbit hole went straight on like a tunnel for some way, and then dipped suddenly down, so suddenly that Alice had not a moment to think about stopping herself before she found herself falling down what seemed to be a very deep well.

The scene of our heroes falling down is a trope, in myths and fairy-tales: think of Tolkien’s piece, in The Hobbit, where Bilbo dreams of falling through a crack in the cave’s floor (only to wake up and find out that the dream was partially true and there are fucking Orcs coming out from the walls like aliens) and the inspiration Tolkien took for it from Algernon Blackwood’s theatrical piece Through the Cracks. Tolkien himself admits Blackwood’s influence, at least in the usage of the word “crack” in a – then removed – note to the translation of names in The Lord of the Rings.

At any rate, our two friends dive and for once we see the scene through Rat’s eyes: the roles are reversed, Mole is now our guide, and Grahame pairs us with the one character who’s venturing into stranger lands. Rat has the impression of venturing down for a very long time, and us with him, until we reach a place where he can stand again. It is dark and air is little, but Mole strikes a match (something we also see Bilbo doing in a similar situation) «and by its light the Rat saw that they were standing in an open space, neatly swept and sanded underfoot».

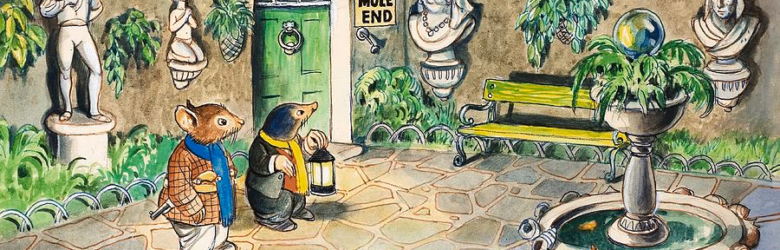

Mole End is described in detail, this time, with highly human features and a little kitsch: he has his name written in Gothic letters, painted over the bell-pull at the side of his little front door, and wire baskets with ferns on the wall in his fore-court, alongside two garden seats (one unused, a detail that speaks again to the condition o bachelor for our hero before he met Rat).

On the wall, alternated with the fern baskets, Mole has «plaster statuaries», fake sculptures in plaster depicting Garibaldi, the infant Samuel, Queen Victoria and «other heroes of modern Italy», which is rather kitsch on his behalf but not so strange a description. The intent here seems to be the description of a character who wants to imitate some of the upper-class habits, without having the means to do so.

In her Annotated Wind in the Willows, Annie Gauger suggests that the details within the description Grahame gives us of Mole End are sometimes recurring from another parodic book meant to convey the same idea: The Diary of a Nobody, by the brothers George and Weedon Grossmith, with illustrations by Weedon, originally published between 1888 and 1889 on the magazine Punch and firstly published as a book by J.W. Arrowsmith in 1892. The book describes the daily life of a clerk, one Charles Pooter, his wife Caroline, his son William Lupin and their friends. The book starts where Charles and Carrie have just moved to a new home at “The Laurels” in Brickfield Terrace, Holloway, with which Gauger and Peter Hunt, who wrote a whole piece on “Language and Class in The Wind in the Willows”) sees a resemblance I honestly don’t see.

What is a lot more interesting is the social aspect of Mole End, which hint to his good nature and make him even more likable. First of all he has a pathway for playing skittles, «with benches along it and little wooden tables marked with rings that hinted at beer-mugs». Skittles is a European game, related both to bowling and to the game of bowls, still being played in Italy and France, historically popular especially among the working class as an after-work leisure.

Secondly, he has a small quaint round pond with a shell-decorated rim and gold-fishes (that are most likely dead, after he’s been absent from Spring till mid-December, although Grahame tried to deny it in answering the letter of a preoccupied fan).

Out of the centre of the pond rose a fanciful erection clothed in more cockle-shells and topped by a large silvered glass ball that reflected everything all wrong and had a very pleasing effect.

The silvered glass ball, also a rather kitsch touch, was a rather popular object, sometimes also referred to as “witch ball”: things like this were traditionally used as a fishing float and they owe their name to the un habit of tying up women suspected of witchcraft, throwing them in the water and hanging them only if they didn’t drown. They were hung in English cottage windows during the XVI and XVII Century, to ward off evil spirits, and remained in fashion for a very long time. The idea should be that the ball reflects the world upside down and makes it impossible for the witch (who must not be a very good witch) to make sense of it and enter the house. The non-hanging variety of silvered balls, such as the one our Mole is showing off at the top of his fountain, is usually called yard globe and it’s an extravagant good-luck charm. King Ludwig II of Bavaria had lots of them in the gardens of his Herrenchiemsee palace, but by 1908 – when Grahame was publishing his Wind in the Willows – these kind of ornaments were dramatically out of fashion.

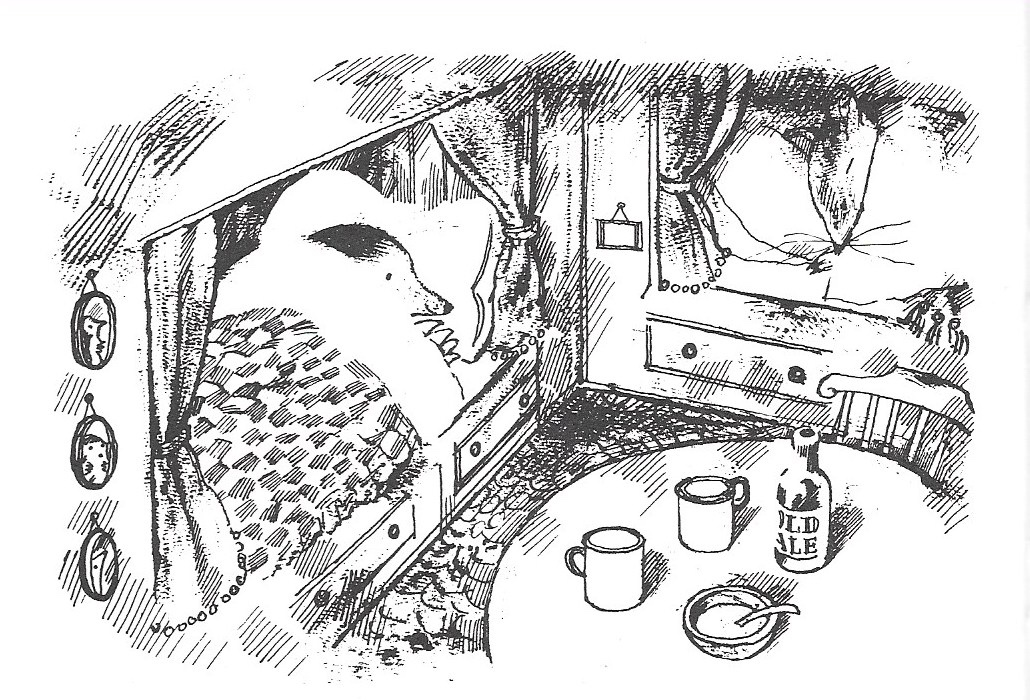

Mole is enchanted by the sight of his old house, but his enthusiasm fades away as soon as they set foot inside the house: its dismal appearance, its small dimensions and dusty state, prompt out friend to collapse on an armchair and regret his idea, being probably in part ashamed and making no mystery of how the house pales in comparison with Rat’s residence. But Rat is absolutely enthusiastic to be in Mole’s house and spares no praise.

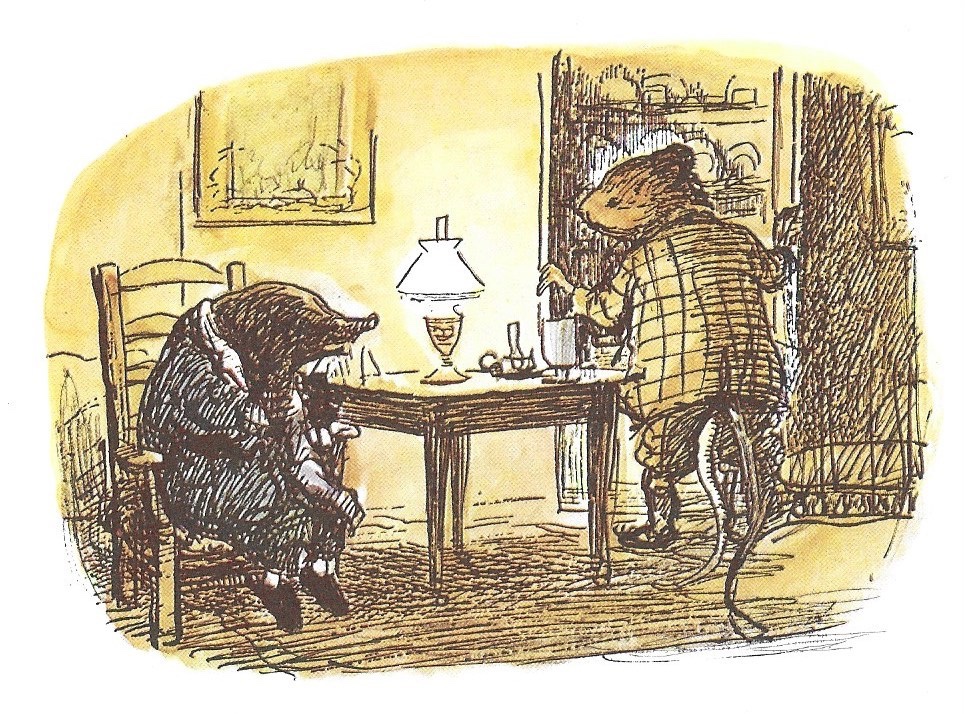

He was running here and there, opening doors, inspecting rooms and cupboards, and lighting lamps and candles and sticking them up everywhere. “What a capital little house this is!” he called out cheerily. “So compact! So well planned! Everything here and everything in its place! We’ll make a jolly night of it.”

He takes the situation into his own paws: he sets off to find some wood for the fire, prompts Mole to dust off the furniture (even giving him directions in his own house), and then they scavenge in the house for food. They find a tin of sardines, a box of crackers called Captain’s Biscuits, some mustard, and a German sausage wrapped in silver paper. Rat goes down to the cellar and comes up with some bottles of beer, still praising how comfortable and well-furnished Mole End is. The biscuits are also mentioned in J.K. Jerome‘s Three Men in a Boat as a not very merry form of sustainment.

For the next four days he lived a simple and blameless life on thin captain’s biscuits (I mean that the biscuits were thin, not the captain) and soda-water.

Their recipe can be found in Modern Cookery for Private Families‘ by Eliza Acton (1845):

Make some fine white flour into a very smooth paste with new milk; divide it into small balls; roll them out, and afterwards pull them with the fingers as thin as possible; prick them all over, and bake them in a somewhat brisk oven from ten to twelve minutes. These are excellent and very wholesome biscuits.

Spoiler: they are not excellent, let alone wholesome.

It is simply delightful, however, how Grahame describes us the way Rat asks about the house, and how Mole came in possession of certain prints, and how he doesn’t interrupt him, until he’s cheered up and way beyond, even if he’s starving and would really like to seat at the table. Couple goals.

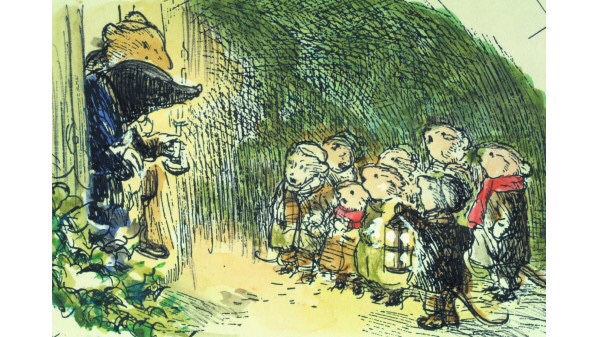

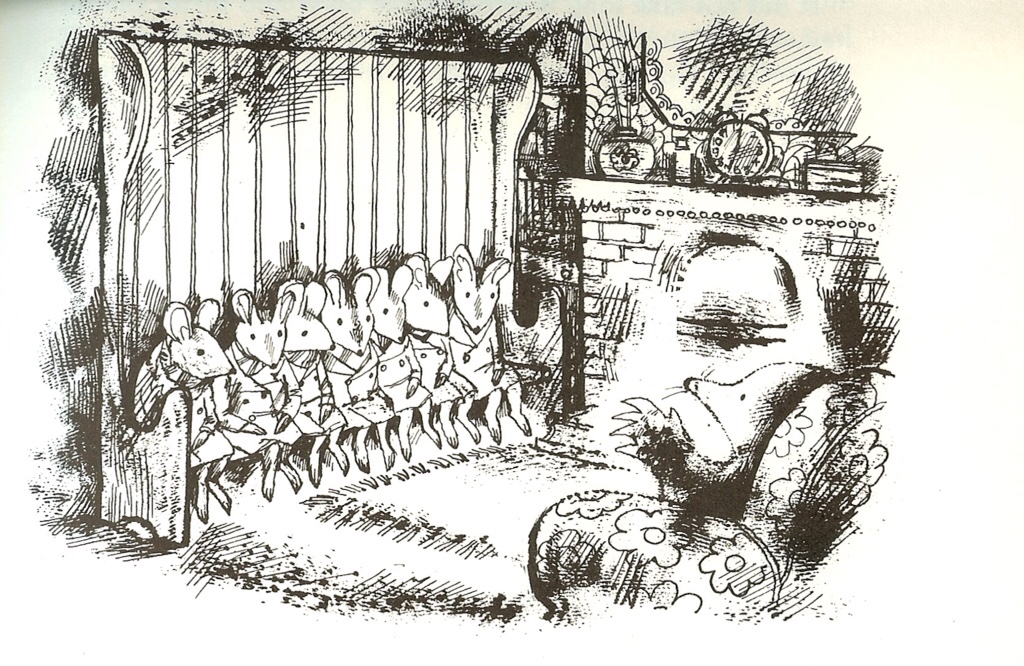

Rat won’t be able to have his sardines dinner for two, in any case, because this is the moment when we are made to remember that it’s mid-December. The two hear some rustling, outside, and voices.

“I think it must be the field-mice,” replied the Mole, with a touch of pride in his manner. “They go round carol-singing regularly at this time of the year. They’re quite an institution in these parts. And they never pass me over—they come to Mole End last of all; and I used to give them hot drinks, and supper too sometimes, when I could afford it. It will be like old times to hear them again.”

Kenneth Grahame treats us too to the Carol sung by the Field Mice.

“Villagers all, this frosty tide, Let your doors swing open wide, Though wind may follow, and snow beside, Yet draw us in by your fire to bide; Joy shall be yours in the morning!

Here we stand in the cold and the sleet, Blowing fingers and stamping feet, Come from far away you to greet— You by the fire and we in the street— Bidding you joy in the morning!

For ere one half of the night was gone, Sudden a star has led us on, Raining bliss and benison— Bliss to-morrow and more anon, Joy for every morning!

Goodman Joseph toiled through the snow— Saw the star o’er a stable low; Mary she might not further go— Welcome thatch, and litter below! Joy was hers in the morning!

And then they heard the angels tell “Who were the first to cry Nowell?

Animals all, as it befell, In the stable where they did dwell! Joy shall be theirs in the morning!”

It is always kind of unsettling to see animals celebrating Christmas, but even Tolkien wasn’t disturbed by the very delicate way Grahame presents the topic (very differently than C.S. Lewis in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, where the witch is evil because she banned Christmas and Santa Clause gives children weapons to slaughter her…).

The carollers are invited in, to Mole’s delight, and Rat arranges (and personally pays real money) for one of the mice to go to a shop and buy the necessary supplies for a feast. The arrangement isn’t at all unlikely the arrangement between Ebeneezer Scrooge and the street lad on Christmas morning. They cook up some mulled beer, have the Field Mice recite some more verses and then they chatter with gossip of the neighbourhood.

When the Mice eventually hit the road, and the two friends can retire, Mole can do so in great joy and contentment. He was able to honour the Field Mice better than he had ever been, he has his friend with him (who has accepted and even praised his past way of life without any sign of judgement) and his house is even better, at his eyes, now.

But ere he closed his eyes he let them wander round his old room, mellow in the glow of the firelight that played or rested on familiar and friendly things which had long been unconsciously a part of him, and now smilingly received him back, without rancour.

Again, the house is treated like a character, able to hold a grudge.

He was now in just the frame of mind that the tactful Rat had quietly worked to bring about in him. He saw clearly how plain and simple—how narrow, even—it all was; but clearly, too, how much it all meant to him, and the special value of some such anchorage in one’s existence.

I think this is one of the most beautiful pieces in the relationship between Rat and Mole, however you want to look at it: though Mole is clearly dependent on Rat on lots of things (including money), Rat never uses this to bind the friend furtherly to him. On the contrary, he knows that an even stronger bond will arise if his friend is set free from his worries. And this is how we leave them.

Your articles on The Wind in the Willows are superb!

More later, SGM.

Well, thank you!